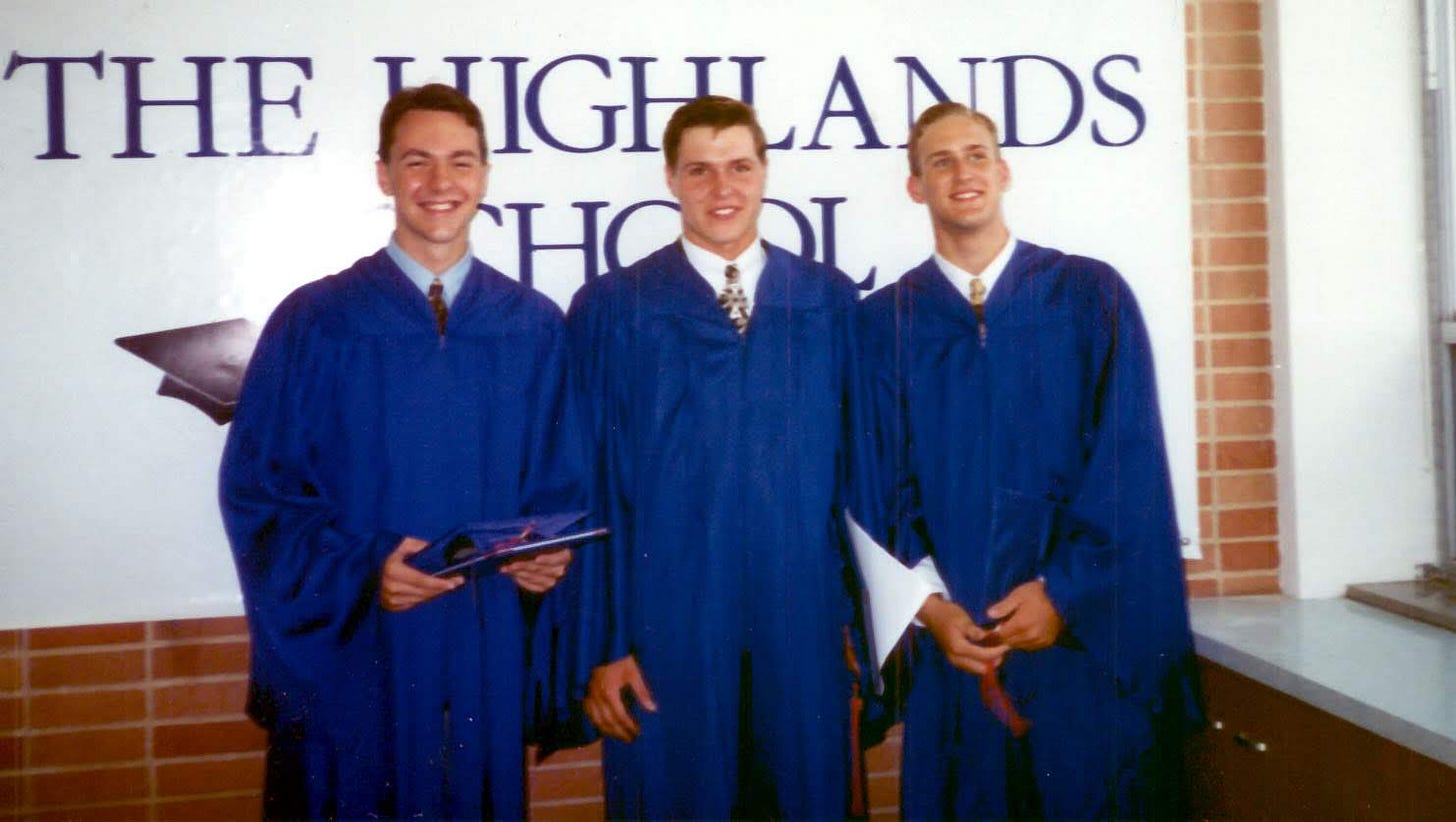

Dallas, 1995

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

That first time in Dallas, fresh off a plane from rural Upstate, I unwittingly stepped into the beginning of the rest of my life.

There are certain demarcation points in life, clear forks in the branching path, and whichever road you choose, it changes your course forever.

Even if you can’t see that from there. Especially then.

I was 17, and it was only my second time in an airplane. As I exited the cabin, the heat hit me like a thrown comforter, pulled straight from the dryer and lobbed at my head. I walked the gray carpet up the jetway to the terminal, my bag in tow, disoriented by the sudden change in climate, and came blinking into the bright light of a Texas summer afternoon.

It was August of 1995. Alanis Morissette and the Toadies had the top songs on the radio. Bill Clinton was president. The Cowboys were about to start another Super Bowl-winning season. The internet was still a novel idea. It would be a full six years before planes crashing into the twin towers in lower Manhattan made airports into an Orwellian nightmare. The 90s were a time when you could meet a friend with a layover for lunch at an Airport food court, and security, such as it was, wouldn’t even think twice.

My family had walked me to my gate back in New York, because the world was still human then. And for much the same reason, my priest-minder stood there waiting for me at my destination, wearing his characteristic wry grin beneath rimless glasses, like he knew something you didn’t, but he was about to share it, and you were going to be so entertained when you found out.

A balding man in his early 40s, he was lean and athletic, and his understated speaking voice buzzed around the edges with a kind of boundless, childlike energy. He wore a white guayabera over his clerics and Roman collar, and he welcomed me enthusiastically before leading me towards the parking area.

He was my uncle’s cousin, and he had started giving retreats to the boys in my family a couple years prior, before being re-assigned from New York to Texas. We knew each other fairly well by the time my plane touched down at DFW, and it was at his invitation that I had decided to spend part of my summer as a counselor at a summer camp for Mexican boys.

He hadn’t come by himself, but for the life of me I can’t dig up the memory of who was with him, even though I’m sure it was someone I later came to know. Priests from his order never traveled alone. Whoever it was, together, they led me to a nondescript Plymouth minivan, and we pulled out on the sun-bleached asphalt and onto the highway, where we made our way through the seemingly-endless flat expanse of Dallas suburban sprawl. Everywhere I looked, there was a sea of strip malls and restaurant chains, the static-spark energy of commerce heavy on the tide of traffic. As a kid from a dead-end road in a tiny town in the backwoods outside Binghamton, this was a major civilizational upgrade, and I was a bit starstruck with it all.

Unbeknownst to me, I had just taken the first steps in a whole new life. I couldn’t see it from there, concealed as it was beneath the disguise of a simple two-week summer escape.

What I did know was that I was stir-crazy and desperate for adventure, and for the first time in a long time, I wasn’t stuck staring at the same four walls, wanting to get the hell out of Dodge.

Small-town living was, for me, like wearing chains. In Kirkwood, my little one-horse redneck town, I felt like Harrison Bergeron, gazing out windows at defunct farms, trailer parks, and ancient gray-brown barns surrendering slowly to entropy in a slow, lazy slough of bent and broken boards. It was a landscape like Ireland — or so I’d been told by those who’d been — lush and verdant and rolling with hills, but with none of the Irish charm. The most magical thing that ever happened growing up was when the fireflies slow danced out back in the warm evenings of late June, blinking out indecipherable messages to their companions under a glittering canopy of stars.

But now I was in Texas, just as big and bright in person as I’d heard about in the songs.

The possibilities felt endless.

When I arrived at the school, the place where I’d be helping to lead a summer camp for rich young Mexican heirs, I was introduced to a young man my age at the bottom of the stairwell heading up to my room. He stood sweating in a red soccer shirt and backwards baseball hat, having been working the school grounds with the landscaping crew for his summer job. He was the nephew of my priest-friend, and while I was anxious to check out where I would be staying, in just a few minutes of conversation, we hit it off like we’d known each other our whole lives.

The next day, on the way to Fort Worth for a day of Texas-themed sightseeing, we sat in the back seat of a car mapping out the Venn diagram of our respective interests and finishing each other’s movie quotes as his mom and her priest-brother chatted quietly up front, throwing approving glances back every now and then.

Later that afternoon, I realized with a shock as I walked the old stockyards, laughing with my new acquaintance over rough-hewn crates of penny candies, that I was 17 and had never really had a friend before. Someone who got me and shared my interests, sense of humor, and enthusiasm.

And now I did. This was just something qualitatively different than anything I’d experienced in nearly a dozen years of public school.

The camp itself was fun, but the memories are all a blur, like candies melted together in a bag after sitting too long in a hot car. Afternoons spent supervising as the boys screwed around in the pool. A trip to two different Six Flags in the span of a week. A dinner at Medieval Times. Cafeteria Mexican food more authentic than any taco I’d ever eaten growing up. A shopping trip to the local mall where each young boy was handed a wad of spending cash bigger than I had ever seen. A trip back from Houston to Dallas on I-45, with me driving one of three Ford Econoline vans through rain so heavy I may as well have been piloting a submarine. When the rain cleared up, we raced each other at speeds well above the posted limit down the wide open stretch of straight, flat highway.

That camp was, for reasons that were never fully explained to me at the time, the last of an era. It was essentially a two-week recruitment session designed to be so much fun, those boys would go home and beg their well-off parents to pay the tuition and send them to the states for school. But the Mexican peso crisis the previous year had dangerously weakened the country’s economic situation, and made it a dicey proposition for even the wealthy to send their boys to an expensive American boarding school. Enrollments were drying up, and the Texas campus was forced to shut down. Simple as that. The few boarders who remained interested would be consolidated into an academy at a different location somewhere in the Midwest.

That left an entire floor of the building permanently empty. A floor full of furnished dorm rooms, as vacant as a ghost town. I didn’t want to go back to my depressing little Podunk hometown. I had zero interest in enduring another year of mind-numbingly boring homeschool, working afternoons and weekends at the local hardware store so I could buy video games, and clothing that didn’t come to me in a black hand-me-down trash bag from my cousins across town. I saw an opportunity floating in front of me, and I reached for it like a drowning man. I had found a vibrant city full of young people and things to do, and best of all, I’d made a friend. Several, in fact, as I’d gotten to know some of the other cast of characters who also lived at the school.

The Mexican academy was just one segment of the larger campus. Most of the facility was dedicated to The Highlands, an American private Catholic school that was just about to open back up for the fall semester. I talked to the priests and asked if there was any way I could stay for my senior year. I couldn’t pay the tuition, I told them, but I’d be willing to help out with what I could.

To my surprise, they agreed.

In retrospect, I think they may have been recruiting me as well, and were hoping for me to ask. But I was too young and naive to see any such machinations. I felt as though I’d won some kind of jackpot. As the child of a large family who had always shared a room, I was thrilled to have my choice of accommodations from the now-empty second floor. I chose two by the stairs, with an adjoining bathroom in the middle. I’d use one room for my desk and computer, the other for my bed. It was like having my own apartment.

I flew home with my heart set on my new mission. I couldn’t take being cooped up anymore. I’d be 18 in a few months, I told my parents, at a family barbecue over the noise of cousins rope-jumping into the family pond, so while I’d love to get their blessing, I had decided I was going either way.

I had made up my mind, and nobody was going to change it.

Seeing this, my folks shrugged and said OK.

Over the years, I’ve spilled no small amount of ink about the Legionaries of Christ, the cult that ran the school. It would later be revealed as a crazed sex-predator’s religious ponzi scheme masquerading as the most dynamic and fastest-growing order of priests in the Catholic Church. But that would come later, after things took a darker turn.

Even knowing what I know now, I am not exaggerating when I say that I was about to embark upon the best year of my life, if such things are measured in terms of total hours of sheer happiness.

I returned a week or so later, the school year in Dallas starting earlier than I was used to back home. The first order of business was getting a proper uniform together, my blazer and patch and gray uniform pants all coming to me courtesy of various helpful mothers involved with the school.

When classes began, we spent our mornings lined up in perfect rows on the epoxy-pebbled flooring of the glass-walled room called “Purgatory,” our uniforms receiving cursory inspections from teachers with big hearts pretending they were disciplinarians, their knowing looks directed at upper classmen whose job it was to exemplify order while seeing through the charade. I couldn’t have cared less about academics, at that point, but I loved starting each day in my all-boys theology class, as we followed our teacher’s emphatic instructions to “pursue the truth like rabid dogs,” arguing our way through deep religious concepts we had never before explored.

The true joy was in the companionship. I had never been part of such a tight-knit group, where everyone was friends with everyone.

I wasn’t equally close to everyone, but there wasn’t a single person I didn’t like. Perhaps this was easier to do when total number of students in junior and senior years combined were fewer than twenty.

We did everything together.

We swam in each others pools and went to each others parties and went out together to eat. I bummed nachos off my friends at Chilis, because I had no spending money of my own, but despite my teenage hunger, I didn’t particularly care. There was a rotating schedule of women who made delicious meals for the priest community, of which I was an honorary part, so I never went hungry for long.

For the first time in my life, I was part of something bigger than me. And every friend I made shared my beliefs, which at that time of my life were becoming more important than they’d ever been. I was just as likely to find myself kneeling beside my friends at Mass as I was to sneak an illegal beer with them at Jazz club while choking my way through the unfamiliar pleasures of a cigar.

I went on road trips to New York City and to Mexico. I met and dined with famous business men and athletes. I saw the most beautiful display of stars, the ink-black sky unblemished by even a hint of light pollution, as I stood outside an opulent marble-floored seminary in the mountains of Monterrey. I nearly died and went to heaven the first time I tasted real Mexican food at a street cafe outside of Saltillo. I rode on the back of a friend’s motorcycle, skimming between the lanes of Friday night traffic, to watch a championship rodeo in Mesquite. I went off-roading in an old Ford pickup on an undeveloped urban lot during a rare Dallas snowfall. We laughed when some of the other guys got stuck in their Jeep, and tried not to laugh when we ripped off the Jeep’s front bumper trying to pull it out of the ditch.

I saw Toto and Three Dog Night in concert by accident for a single measly buck. I managed to keep a straight face after taking a big bite of apple pie, completely mold-ridden beneath the top crust, because I had somehow wound up as the lone high school guy at a Waffle House with five college girls, and I was not about to mess that up. I did missionary work in the sparsely-populated mountain villages of Michoacan, stood guard over a young man having schizophrenic visions of the Virgin Mary and paranoid delusions of a Communist plot among local children, spoke in broken Spanish to indigenas cooking hand-made tortillas over open wood fires in dirt-floored huts, and drank water pulled from beneath a layer of dust and grit out of open 50 gallon drums.

I did door to door evangelization in the poorest neighborhoods of the Bahamas, purchased guava-jellied pastries from a monastery bakery under palm trees and a thick layer of morning fog, ate conch and plantains as I watched the festive dancing at the celebration of Junkanoo, and walked the white sand private beaches of the Bacardi rum family at sunset.

And then I came back to Dallas, and met her.

At this point in the reel of memories, all the other images from that year begin to pale in comparison, like a technicolor film that fades to gray.

There was nothing otherwise special about that day. I was coming off the high of my Caribbean trip, trying to re-adjust to being back in the drudgery of school, when I walked outside the front entrance after class and saw her there.

My priest-minder was the one who made the introduction. He said she used to attend the school but had been away, something about having just come back from a different school for girls considering religious life on the East Coast, and was going to be a student again full time.

She had a slight build, dark hair, and porcelain skin. A strong but still-feminine jawline. She was about 5’6”, in a uniform skirt and button-up blouse, her navy blue blazer slung over her arm.

But what riveted me in place were her eyes.

They were hypnotic. Turquoise blue, piercing and clear, like Maldivian waters. I had never seen eyes like that, and they pulled me in and held me in their gaze, totally paralyzed. My stomach filled with butterflies, and an electric buzz filled my head.

I had never had a hard time crushing on girls, but total love at first sight was something new.

From that moment on, my whole world tilted on its axis in her direction. Nothing else mattered anymore. All I wanted to do was see her. Be with her. Talk to her. Make her mine. I took every chance I had to interact. After stumbling across her one morning on my way to the school kitchen, and catching a glimpse of the way her eyes shone, like gemstones in the morning sun, I would get up every day extra early so I could come downstairs before she arrived. I just hoped I might bump into her by that same door, in that same light, in the hopes I could glimpse something that beautiful again.

I played the usual high school games, talking to her friends to try to get a sense if she was interested. Picking the brain of her cousin. Passing messages through the network of girls who acted as social gatekeepers to relationships. Did they approve of me? Did she even care?

She seemed polite but indifferent. Friendly but elusive. I had no patience, but no choice but to pretend.

I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I was utterly smitten. I had never felt anything so gloriously painful.

It’s been 30 years, so the particulars are now faded and threadbare, like an old concert t-shirt tucked in the back of a drawer. I couldn’t tell you exactly what I did that finally won her over, but I was damned persistent.

After a month or two of this interminable chase, I found out she was going on a prospective-student visitation weekend to the University of Dallas, which was located right next door to our school — and my home away from home. Sensing that it was my best chance to take my shot with nobody else getting in the way, I walked the trail I had traversed so many times through the woods, past the angry, pulsating buzz of cicadas, to the UD campus. I did not have a plan. I just knew I needed to find her. There was a dance that night, and I waited for her there until she arrived, frantically searching the crowd for her face. Ordinarily, I would have been busy noticing all the other girls. But that night, under the spinning neon disco ball lights, only one person in the world existed, and everyone else was just the haystack in which I was searching for my needle.

Those of you who remember the days before cell phones know the feeling. How these things had to happen organically, even if “organically” meant putting yourself at the right place at the right time in the hopes of forcing the perfect coincidence. It took planning and persistence, but if you were diligent, such efforts sometimes paid off.

I was sliding into massive disappointment. I didn’t know where she was or what she was doing, but this was not working out the way I had hoped.

Then, right as I was about to give up, she arrived.

I don’t remember if we danced. I don’t remember what we talked about, or where else we may have gone. I do remember walking her to her assigned dorm later that night, standing close together by the entrance under the bright lights. When I finally felt the moment had come to give her a hug and say goodnight, I moved in…and found that my arms refused to let her go.

She made no attempt to pull away.

We stood there like that for what felt like forever, her enveloped by my arms, swaying slowly like a dance. When we finally kissed, the inexorable result of the magnetism between us, it was the most gentle, tender, perfect expression of affection I had ever felt.

If someone had told me that’s what heaven was going to be like, I’d have done anything to go.

From that moment on, we were inseparable. Our chemistry was as addictive as any opioid. But PDA wasn’t a great idea at an ultra-conservative Catholic school, where I literally lived with priests, so we would steal moments to be alone whenever we could. Since I lived in the building, I lived at the school, I knew all nooks and crannies. We’d lock ourselves in the elevator to the residences, that the teachers and the students didn’t use. We’d head off to the woods by the soccer field, hidden from public view. And eventually, when I figured out where she lived, I’d borrow the ten speed bike that the priests had and pedal the 3 or 4 miles to her place after dinner in the evenings, making the same long trip back home again several hours later.

I was, by this point, a legal adult, and not technically a member of the religious community. Nobody was checking in on me at night to see if I was tucked in. She lived alone with her mother, a nurse who worked the night shift at a local hospital, so the evenings belonged to us. We would sit in her driveway, or lie on the floor in her living room, just so we could be close and talk. I was committed to chastity before marriage, so I intentionally made myself physically uncomfortable in the hope of keeping my impulses under control. There was no way I was going near a couch, let alone her bed.

There were times when even that was almost not enough. Almost. Hormones and youth are a hell of a cocktail.

She taught me to love U2 when she gave me her copy of Achtung Baby. She told me that she thought of me every time she heard the song Wonderwall. She was half Lebanese, half Mexican — the Lebanese bit was where she got the eyes — and since she spent the first half of her life in Mexico, she was fluent. At my request, she would write me love notes and speak to me over the phone in Spanish, because she made me actually want to learn the language like no classroom ever had. We would go to daily Mass in the evenings at the aggressively underwhelming UD chapel, with its ugly modernist design and its weird ambient smell. It was strangely perfumy, like the lobby of a hotel with a signature scent, and there was always the sound of trickling water from the oversized holy water font. We would sit on the phone at night and talk, each refusing to be the one to hang up, like some cultural cliche. We ate Monte Cristos at Bennigan’s and walked the monorail tracks in Los Colinas under the city lights, and just be together. I learned things about her through the course of our conversations, things she had endured as a child, and they only made me want to protect her more.

And for whatever reason, she felt safe with me. I had no idea who I was, or what I was going to do with my life, but I was too young and too zealous to let that bother me.

The priests eventually found out about our relationship, several months in, and tried to split us up. They were intent on my having a vocation, and they preferred for me to live like I already believed I did. I made it crystal clear that no part of our agreement included me saying I wasn’t going to have a girlfriend. I was adamant that things were going to continue. The screws tightened, be we found a way.

When the time came for us to graduate, panic began setting in.

Senior prom felt like the beginning of the end. When Everything But the Girl’s breakout hit song Missing started playing, I felt every word.

I knew what was coming.

I step off the train

I'm walking down your street again

Past your door

But you don't live there anymore

It's years since you've been there

Now you've disappeared somewhere

Like outer space

You've found some better place

And I miss you

Like the deserts miss the rain

And I miss you

Like the deserts miss the rain

I will emphasize again that I was 18 years old.

To me, that number felt so grown up, so full of freedom and possibility. But I didn’t have a plan, or even an idea how to start. Nobody in my life had ever talked to me about college, and I didn’t know where to go or what to study. A few recruiters had visited us, and I found myself vaguely leaning towards Steubenville, because despite the charismatic stuff, which didn’t appeal to me at all, it felt the closest to what I was looking for.

The last night I saw her, just after graduation, I borrowed a car from a friend who had also taken up residence at the school after returning from the army. It was a 1986 Dodge Omni, a hideous hatchback in shitbox blue that looked like a Volkswagen Rabbit with an extra American chromosome. Wherever we went that night, it ended with us standing in a parking lot in the rain, my arms around her, holding on for dear life, talking about hopes and dreams that would never come to pass.

I knew.

I knew I was a kid playing grownup, and didn’t have the first clue how to make it happen. I was due to get on a plane to go back to New York the next day, and as I stood there, our tears blending in with the rain, I would have given anything to marry that girl if I only could have found a way.

I drove home that night feeling like my heart was being ripped out of my chest. I sobbed like a child. It was an impossible situation, and I was powerless to change it.

My trip home to New York was brief. I had committed myself to spending a year doing volunteer work with the Legion, which was at least partially my way of procrastinating on figuring out what to do next. My two best friends from Dallas picked me up from my parents house and drove me to our “coworker” training at the Legion seminary in Cheshire, Connecticut.

Along the way, we somberly sang along to the Trace Atkins’ song, “There’s a girl in Texas.” Each of us had left the girl we loved behind, and it was a hard stretch of road.

I hate country music, but damn if it didn’t hit me right in the feels:

When I rode out of Dallas

Chasing down a dream

I thought I knew what I was looking for

But the neon nights have blinded me

'Til I'm lost in Tennessee

Not sure I know who I am anymore, but

There's a girl in Texas

There's a girl in Texas

There's a girl in Texas

That does

That summer, after my training turned into me being lured into the discernment program, I used a contraband CD player to listen to Amplified Heart on an endless loop. It was the album that had produced our prom song.

When she arrived unexpectedly for her older brother’s religious professions — he was a seminarian there — the sight of her was like a gut punch, and utterly shattered the illusion I could ever be a priest.

I quickly became a disruptive force — love, and a forced attempt at vocation can do that to a man — and my anxiety was spiraling out of control so hard I couldn’t shut my mouth. I was stirring up a rebellious spirit among my fellow discerners, so I was asked to leave the seminary but “keep discerning.” Instead, they sent me to Atlanta, with one of the two friends I’d driven there with.

My desire to see her again, to be with her, was the thing that got me through the next six months of escalating tension. They manipulated and lied to me in spiritual direction, they abused my trust, and they did everything they could to keep us apart.

The harder they tried, the more I clung to the idea of her.

Finally, during the Christmas break of 1996, I made the decision not to go back. Almost a full year after I first met her, I walked away from the Legion’s bullshit, and their lies, and the literal cult I hadn’t seen until at last, finally, I opened my eyes.

When I left, I thought I was finally free. I had one last job to do — a two-week, door-to-door evangelization mission in Miami I had spent months planning and was scheduled to direct. In January of 97, I made my way with a friend down to Florida for my farewell tour. The way the Legionaries treated me, knowing I was on my way out the door, was the final straw. They were already closing ranks, and I was ready to start burning shit down.

I stopped to visit her, on my way back from a mission in Miami. She was staying with a family near Washington, DC, where she was getting therapy to address childhood trauma, and thinking about going to college.

Every time I was away from her, I was nervous to see her again. Every time I saw her, it was like the first time all over. She was doing well, and seemed genuinely happy.

We still had no idea where to go from there. And if she was friendly, even affectionate, there was a quiet-but-growing feeling that she was pulling away.

Months earlier, I’d been given a warning by a mutual friend who worked with her at a local supermarket the summer after graduation. He told me that she hadn’t exactly been pining over me in the same way I was over her, and that he had the impression she was going out with other guys. He was worried I was going to get hurt, but I was too enamored to really listen, and too protective of her not to make excuses.

After all, it wasn’t as though I thought I could keep her confined to a relationship with no clear future. Our lives seemed to be keeping us apart, and I had no clue how to bring us back together again.

But in the back of my mind, I knew it was a red flag. We had no agreement on how we were going to make things work long distance, and the meddling of the Legion had kept us from being in contact for over half a year. To make matters worse, the smear campaign around my sudden departure from the movement had turned her mother against me, and all three of her siblings were in active religious formation with the Legion. She had known before I had the chance to tell her that I had chosen to leave. They had called her mother as soon as I had notified them.

They were ruthlessly efficient about spreading rumors.

I did the only thing I could do, and went home to New York. I got a job fixing computers, and another one hosting at a hotel restaurant. I threw myself into work. Inside, I was falling apart. Leaving the cult was not as easy as I had hoped. They had changed the way I thought. They had influence over my friends. They tried to destroy my reputation in the eyes of the people who had come to make my life a joy. They had pulled the rug out from under the best year of my life.

That summer, when my buddy who was with me in Atlanta finished up his year and moved home to Idaho to work, he invited me to come stay with his family. To be honest, I’m not sure what his thinking was. I suspect he knew I was hurting and needed to stay busy. And did not need to be at home, alone.

I took him up on it. I drove my beat-up old Chevy Celebrity station wagon across the country, which died as soon as I arrived. But I didn’t miss it much. We did hard physical work over long hours, driving countless miles across the stunning landscapes of Pacific Northwest, installing pumps in water wells for countless hours per day. On the weekends, we chased cows from pasture to pasture, fixed fences, went rafting, crashed weddings, drank beer.

I met other girls, but it was never the same. I missed her so damn much, but we were in relationship limbo.

On our way to Ohio to start college at Steubenville that August, my buddy and I took a long road trip. We went first to Seattle, then down the Pacific Coast highway. We slept on beaches. We body surfed the waves. I got sun poisoning so badly that our trip through the blistering heat of Phoenix made me want to die.

And then we stopped one last time in Dallas.

We had both left girlfriends there, and we both needed to know where we stood.

She had moved back home. I let her know that I was in town, and asked if we could get together. She agreed. I drove over to pick her up, and sat in the truck and watched her leave her house the same way I’d watched her do a hundred times. The way she abruptly opened the door, turned abruptly, locked it, then nearly jogged over to the car.

Like she was trying to escape something, too.

We spent the evening together, talking about the changes in our lives. She told me that she had been seeing someone else, but the level of commitment was unclear. I hated to hear it, but I wasn’t so much jealous as confused. Everything about us had seemed so clear. So certain. And now, I could see that our priorities had begun to diverge, and that nothing was sure anymore.

The chemistry was still there, just like it always was. She could intoxicate me by just her presence. But there was a hollow note to it, as we sat there in the growing darkness of twilight and talked, in the living room of a friend who had given us the use of her house while we were in town.

Like all drugs, in time, the euphoria begins to fade, and the side effects become more clear.

Chemistry, but not connection.

It occurred to me, somewhere along the way, that I had no idea what about us actually worked. I knew I was utterly infatuated. And I knew she seemed to like me for some reason. But I didn’t know where our Venn diagrams overlapped. I had no idea what a future with her would even look like. She had always been happy to take a more passive role and let me lead, let me run my never-ending mouth while she listened and only offered feedback here and there. I had always been the one to call her first, back when texting had thankfully not yet been invented, because I couldn’t bear the thought that she might not call me if I didn’t.

Was any of it as real as I had thought it had been?

At the end of that evening, in the wee hours of the morning, under the blue-grey light of a nearly full moon, I dropped her off at her mother’s house one last time. We said our goodbyes, and something deep and sad and strangely certain within me told me that it was the last time. That we had given it every chance to flourish, and it had fallen apart. It was the moment I knew it was really over, watching her lithe, feminine frame saunter towards her house.

I waited until she had unlocked the door and made it safely inside, just like I was brought up to do. We waved to each other one last time, and then I drove away.

And never spoke to her again.

Not a message. Not an email. Not a Christmas card.

In August of 1997, the person who had mattered more to me than anything, ever, walked out of my life for good, and I had no good reason not to let her go. Just a dull ache, a wistful sadness that something so incredible and so intense could end so anticlimactically, and so soon.

At times, over the years, I’ve wondered whatever happened to her, and if she’s well. It’s bizarre to think that someone who meant the world to you once can become, like the song says, just “somebody that you used to know.” Unlike many of my high school peers, who have stayed in touch here and there over the years, she is a social media ghost, with no presence online for me to surreptitiously peek in upon. She shows up in an occasional photo on other people’s Facebook pages, looking somehow familiar but nothing like I remember her to be, and I hope that she is well. That she found the happiness she deserved.

From everything I wanted to nothing but a half-forgotten ghost. Life is so relentlessly strange.

These memories, now three decades gone and more, came rushing back last week when a friend told me he was bringing his own daughter to the University of Dallas for a prospective student visit. I was suddenly right back there, walking that trail through the insect buzz of the mesquite trees, making my way to that fateful dance.

Dallas was a year that forever changed my life. It is impossible to say how different things would have been if I had not gone. Some of the friends I made that year are still in my life today. Some are godparents to my children, others are friends I see too rarely, but when we get together, we effortlessly fall into the rhythm of old times.

The decision that some of my high school friends made to go to Steubenville helped influence me to do the same. This led to another four years of adventures, with some of the old faces and even more new ones. More lifelong friendships were forged. More branches on the tree of life. All of it eventually landed me, very unexpectedly, in Phoenix, where I got a stupid job I didn’t like. And at that stupid job, I met the beautiful, incredible woman I would go on to marry, together now for 24 years, and married almost 22, and would lead to our eight amazing kids.

I’ll save that story for another time.

I tried to go back to Dallas once. Thought about moving there, briefly, back in 2016.

But as I drove those streets, from Irving to Deep Ellum, Grand Prairie to Highland Park, rediscovering my old stomping grounds, I was struck by the way you really can’t ever go back again. My memories of Texas were forged not by the place, but by the people in it: Hugh and Paul, Joe and Mike and Brian and Thierry, Katarina and Katy, Claire and Suzy and Maria, Margie and Yvette, Tom and Ian and Ryan and Laurence, Sue and Molly, and yes, even Br. Douglas, Fr. Marty, and Fr. Daniel - and an even larger cast of supporting characters. Names that will mean nothing to most of you, but meant everything to me in my first time away, making a home away from home.

Without the same people, the same dynamics, the place felt empty and alien and not at all the same.

It’s fascinating, this bifurcating tree of choices in our lives. They can be strange and inexplicable. When we look back, we see them for how significant they were. But in the moment, we have no idea of the sheer consequentiality of them. Another day, another choice, another step forward from cradle to grave.

Our young faces and strong bodies have transformed, diminished with the wear and tear of age. Instead of a life left mostly in front of us, we spend more time these days looking back, at the life that’s now behind.

We will never be young again, but we’ll always have Dallas in 1995.

Glad I subscribed. (Been a reader since 1P5 days.) Perhaps one day I’ll have something more compelling or interesting to say than this, but you’re just a fine writer.

You just blew my mind, Steve. What a gift! What happened to your writing? Is it AI "unbeknowst"? If so, keep on using it, "unbeknowst". If it's AI-free, you're at the top of your game and AI just met its match.

I do not want to turn your head, but that was "beautiful." I read every word (and as you know, I can barely read any more because my aging eyes give out before I'm ready to stop reading). And I want MORE. So, what to do? Write an autobiography entitled "My Life Thus Far." Ah, I think that title may be taken. "From Here to Eternity." Damn, I'm not much in the imagination department. (Did I just curse? On St. Paddy's Day?) Name it something that indicates "I'm not through yet, sequel to come."

And just think: THE MOVIE RIGHTS. That's where the real money is made.

I would like to include a song to accompany that wonderful description of your 1995. Is there a song centered on 1995, as is appropriate? If there is, I'll circle back. You included some song references yourself. Great.

Keep on writing. What happened at Steubenville?