Fanaticism & Art: You Can't Influence a Culture You're Hiding From

Conservatives and Christians talk endlessly about the culture war. What if they actually tried to figure out how to win?

Have you subscribed to The Skojec File yet? It’s only $5 a month, gets you access to our community and exclusive member content. Most importantly, it helps me support my family and keep providing quality content for you to enjoy!

Rob Henderson is a fascinating thinker I’ve only stumbled across recently. His Twitter bio says a lot to help explain him in just a few words: “Interested in human nature. Sharing what I learn.”

I’d be kidding myself if I said that Henderson’s style — studying what makes us tick and then sharing it in concentrated, curious bursts — wasn’t an influence on my approach to The Skojec File. I like the raw info dumps, the page torn out of a book I might never get around to reading, the moment of unexpected insight where a concept is illuminated so perfectly it triggers an epiphany.

That’s what happened to me today, and I found myself writing about it before I had time to fully process what I was thinking about. (That, by the way, is how you know you’ve found gold.)

Today, Henderson tweeted an excerpt of the book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, by Eric Hoffer. Originally published in 1951, with the lessons of World War II fresh in mind and Stalin still in power, the book “depicts a variety of arguments in terms of applied world history and social psychology to explain why mass movements arise to challenge the status quo. Hoffer discusses the sense of individual identity and the holding to particular ideals that can lead to fanaticism among both leaders and followers.”

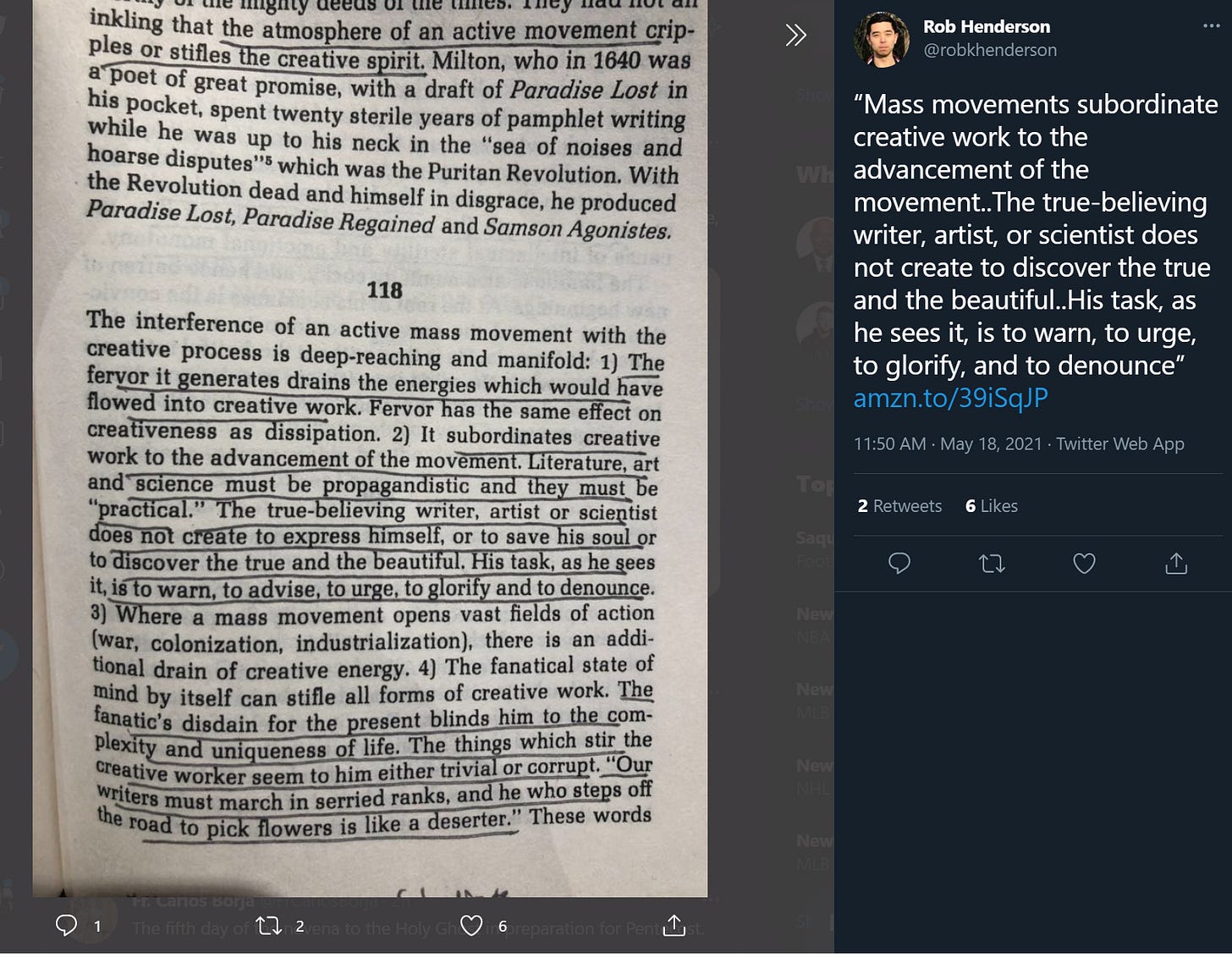

Henderson’s tweet seems strangely to have disappeared since I started writing this, so here’s a screenshot I grabbed for reference:

The writing here is so important I just bought the book. I’ve read only a little outside what’s quoted here so far, but let’s start with Hoffer’s definition of “fanaticism” — it’s obviously controversial, and it’s going to play a big role in this discussion — before moving on to the bit in Henderson’s tweet. (I’ll emphasize and comment on what I think are the most salient bits.)

“The true believer,” Hoffer says, is “the man of fanatical faith who is ready to sacrifice his life for a holy cause”.

The fanatic, writes Hoffer,

is perpetually incomplete and insecure. He cannot generate self-assurance out of his individual resources—out of his rejected self—but finds it only by clinging passionately to whatever support he happens to embrace. This passionate attachment is the essence of his blind devotion and religiosity, and he sees in it the source of all virtue and strength. Though his single-minded dedication is a holding on for dear life, he easily sees himself as the supporter and defender of the holy cause to which he clings. And he is ready to sacrifice his life to demonstrate to himself and others that such indeed is his role. He sacrifices his life to prove his worth.

It goes without saying that the fanatic is convinced that the cause he holds on to is monolithic and eternal—a rock of ages. Still, his sense of security is derived from his passionate attachment and not from the excellence of his cause. The fanatic is not really a stickler to principle. He embraces a cause not primarily because of its justness and holiness but because of his desperate need for something to hold on to. Often, indeed, it is his need for passionate attachment which turns every cause he embraces into a holy cause.

The fanatic cannot be weaned away from his cause by an appeal to his reason or moral sense. He fears compromise and cannot be persuaded to qualify the certitude and righteousness of his holy cause. But he finds no difficulty in swinging suddenly and wildly from one holy cause to another. He cannot be convinced but only converted. His passionate attachment is more vital than the quality of the cause to which he is attached.

Though they seem to be at opposite poles, fanatics of all kinds are actually crowded together at one end. It is the fanatic and the moderate who are poles apart and never meet. The fanatics of various hues eye each other with suspicion and are ready to fly at each other’s throat. But they are neighbors and almost of one family. They hate each other with the hatred of brothers. They are as far apart and close together as Saul and Paul. And it is easier for a fanatic Communist to be converted to fascism, chauvinism or Catholicism than to become a sober liberal.

There’s a lot to unpack there, and I don’t want to get lost in the weeds. It’s not a perfect definition, and I don’t know enough about Hoffer to know where he’s coming from as he writes this, but I do identify with some of what he expresses.

Insecurity and a need for externally-imposed order has driven much of my own religious experience. A need for rules; a guidebook that makes sense out of the universe, and to which I could make appeals when I needed to judge an action, a thought, or a cause.

It’s a much harder thing to say, “because I say so” than “because the Church says so”; the latter is an appeal not just to any authority, but a divinely-guided one. The former is merely a reliance on fallible old me. Saying, “The Church teaches” is one of the most recognizable attempts to definitively shut down a conversation among Catholics, and that’s worth noting.

As for the willingness to lay down one’s life for the cause, again, I recognize within myself that I, too, have always seen this as a means of proving identity and worth. Fighting and even dying for the cause proves I’m on God’s team, and hopefully that keeps me out of the way of His wrath.

I’m intrigued but not convinced by the assertions made in the last two paragraphs above, but in the interest of focusing on today’s topic, I’ll simply let you draw your own conclusions and move on without comment. Suffice to say that I think there’s been a degree of fanaticism in my own approach to faith, and certainly within traditionalism, which is the religious niche I’ve occupied for the better part of two decades. Consequently, I find a a certain resonance here.

Now let’s turn to Hoffer’s assessment as excerpted by Henderson:

The interference of an active mass movement with the creative process is deep-reaching and manifold: 1) The fervor it generates drains the energies which would have flowed into creative work. Fervor has the same effect on creativeness as dissipation. 2) It subordinates creative work to the advancement of the movement. Literature, art and science must be propagandistic and they must be “practical.” The true-believing writer, artist or scientist does not create to express himself, or to save his soul or to discover the true and the beautiful. His task, as he sees it, is to warn, to advise, to urge, to glorify and to denounce.

Let’s pause here for a second. This seems HUGE to me. Absolutely critical. I was struck immediately with the thought that this is what’s wrong with conservative religious culture. Catholics in particular, who used to have a monopoly on art patronage and the masterpieces it inspired in the West, have become terrible at making art or influencing culture. This has been a problem for quite some time. We've got a few people giving it their level best -- architects, painters, composers — but not in a way that’s having a significant impact. Fewer creators still, I think, are succeeding in screen and fiction writing, or film production.

It’s not that nobody is making Christian art, it’s that most of the Christian art being made is badly done. In this regard, the problem Hoffer identifies with "true-believers" preaching via art can't be overstated.

He continues:

3) Where a mass movement opens vast fields of action (war, colonization, industrialization), there is an additional drain of creative energy. 4) The fanatical state of mind by itself can stifle all forms of creative work. The fanatic’s disdain for the present blinds him to the complexity and uniqueness of life. The things which stir the creative worker seem to him either trivial or corrupt.

I consider myself predominately a creative person. And yet I have felt the restraint Hoffer describes since I was a child, hammering out one failed attempt after another at writing fiction. The truth is, I never wanted to go into the Catholic news & analysis business. I wanted to be a novelist. I wanted to make movies. I wanted to tell stories, because stories have so much power. But I went from a nominal cradle Catholic to a true-believer early in adolescence, and that conviction perpetually haunted — and inhibited — my attempts at creative work. I felt that I always had to be moralizing or I wasn’t doing my job. I was committed, just as much as any nonbinary leftist agitprop sci-fi writer is now, to only producing message fic; in other words, fiction where certain ideological themes — in this case, my apologia for my faith and all its many facets — took center stage, and the work itself was to a large degree just the mechanism of delivery. The story could never be just a story. The characters couldn’t live the lives a character of that sort would naturally live. I had to shoehorn them into molds that made them moral examples for the benefit of my audience.

And I knew it didn’t work.

I grew up in a house full of books, many of them fiction. I also made frequent trips to the library. I read tons of sci-fi, fantasy, and comic books growing up, because I was a boy with a big imagination and I didn’t see any reason to read anything that wasn’t fascinating. The fairly broad reading within the genres I wanted to write in must have ingrained in me a sense of what works and what doesn’t, because I knew my stories were falling flat. I wanted desperately to break free of the moral restraints I felt I had to impose on my writing to just let the work breathe and follow its own course, but my own scrupulosity inhibited my ability to simply let go and allow it to happen.

There’s another thing from that last excerpted paragraph I want to revisit before moving on, and that’s this bit:

The fanatic’s disdain for the present blinds him to the complexity and uniqueness of life. The things which stir the creative worker seem to him either trivial or corrupt.

In just these two brief sentences, I feel that Hoffer has explained a great deal of the dissatisfaction I feel as I languish now at middle age.

As I said above, I never intended to become an essayist, an analyst, or a news reporter. In college, I was accepted as a Psychology major; I switched on orientation day of freshman year because something about the idea didn’t sit well with me. I was concerned I would internalize too much about other people’s difficulties and traumas, and that they would haunt me. The idea of being a clinician when I was unable to adequately compartmentalize had begun to scare me off, despite my desire to understand and help people. (Looking back, I have no doubt I made the right choice.) So I decided, on the spot, that I would major instead in Communication Arts, with a concentration in Radio and Television production. I’d always enjoyed acting in plays; I loved putting together my own little television and radio shows when I was a kid and could access to the equipment to make them, and it seemed like a natural fit. Later, I’d add a theology degree as a second major since I was spending all my extra credits on those classes anyway. But I gave a wide berth to the other concentration in my major: journalism. I wanted to tell stories, not just document them. The idea of being a nosy, pushy reporter was repellant to me.

Ironically, as the years went on, my concern over the state of both the Church and the World took a front seat. I couldn’t conquer my own fanaticism about these issues and its effect on my creative work, but I could harness and exploit it as a columnist and essayist.

And that small shift in direction took on a life of its own.

You may recall something I wrote in my piece about midlife crises and changing work that fits perfectly with my Hoffer-derived epiphany today:

I experienced this with 1P5: my work ended up eating its way into every area of my life. And because my work was about religion, going to church felt like work, too. Those were the conversations people would want to have with me after Mass, or at barbecues or cigar nights. The things I experienced at my parish or in my spiritual life became part of the work. And the crisis in the Church loomed over me day and night, with me feeling like I had to go all in to fight it. My boundaries were blurred.

My whole life, I’d been taught to prioritize God and my Catholic Faith above all else. When I worked other jobs, I felt like I was missing my true calling. When I made it my (more-than) full-time job, everything about it was imbued with this same sense of importance; and thus, it knocked everything else — including my family, in many important respects — off my plate. My dynamic with the Church lacked the requisite balance of a healthy relationship. But backing off meant feeling like I was falling short, too.

At the risk of being repetitive, let’s see that quote from Hoffer again:

The fanatic’s disdain for the present blinds him to the complexity and uniqueness of life. The things which stir the creative worker seem to him either trivial or corrupt.

Yeah, I’d say that’s a solid fit for my problem, and my mind is still reeling a bit from the revelation that my experience here is not unique. Everything that wasn’t about the Church and her acute crisis felt like it was just not of critical importance — including the people I loved. So you can only imagine what this did to my ability to engage in creative pursuits. Even now, as I’m breaking free of some of my old ways of thinking, the idea of making art or telling fictional stories feels petty and unimportant with so many big things going on in the world. It’s as though any effort I’d make in that regard would be wasting my time and God-given talent, which was, dontcha know, given to me so I could fight for Him and His Church and against our enemies in the Culture War.

More from Hoffer:

“Our writers must march in serried ranks, and he who steps off the road to pick flowers is like a deserter.” These words of Konstantine Simonov echo the thought and the very words of fanatics through the ages. Said Rabbi Jacob (first century, A.D.): “He who walks in the way … and interrupts his study [of the Torah] saying: ‘How beautiful is this tree’ [or] ‘How beautiful is this ploughed field’ … [has] made himself guilty against his own soul.”6 St. Bernard of Clerveaux could walk all day by the lake of Geneva and never see the lake. In Refinement of the Arts David Hume tells of the monk “who, because the windows of his cell opened upon a noble prospect, made a covenant with his eyes never to turn that way.” The blindness of the fanatic is a source of strength (he sees no obstacles), but it is the cause of intellectual sterility and emotional monotony.

I’m dumbfounded, honestly. This is rich stuff, and I’m still processing it. But with respect to St. Bernard, I think it’s mostly correct. It reminds me, in a way, of Kurt Vonnegut’s brilliant short story, Harrison Bergeron, about a totalitarian society where everyone is forcibly made to be equal by the introduction of physical and mental handicaps. Every time someone tries to think for themselves, to accomplish more, to stand out, they are brutally knocked back into their designated place.

That is what the blindness of fanaticism feels like, only the imposition of impediments comes from within you.

The fanatic is also mentally cocky, and hence barren of new beginnings. At the root of his cockiness is the conviction that life and the universe conform to a simple formula—his formula. He is thus without the fruitful intervals of groping, when the mind is as it were in solution—ready for all manner of new reactions, new combinations and new beginnings.

This, too, looks familiar to me. Whether the fanaticism is rooted in religion, politics, or some other ideology — the position a person holds on COVID, for example, or vaccinations, or election fraud all come to mind — autonomy is traded for ideological automation. Rather than curiosity and questions there are dogmas from which no one may dissent. Rather than critical thought, there is only the race to identify, expel, and marginalize the unclean. Those who have failed to check the right boxes. Those who have failed to go all in for the cause. Those who have insufficiently toed the line. For the fanatic, the purity spiral is the quintessential virtue, because fanaticism cannot exist without a very clear set of boundaries: either you’re in or you’re out; either you’re one of us or you’re an embarrassing failure, a pseudo-member of the club, an unwanted hanger-on.

Fanatics don’t evangelize much, because evangelization is a dance of give and take, where subtle nuances and disagreements play out over time — often long stretches of it. For the fanatic, there is no patience for a gradual, deliberate turning toward belief; there is only a desire for zealous, total buy-in. If you can’t be persuaded to jump in head first, you’re nothing but another target of criticism and shunning, both of which build up the fanatic’s inner world by a process of intense, targeted exclusion. The minute you begin evangelizing, though, you’ve got to let go of the white-knuckle death grip you have on some of your convictions, at least long enough to establish common ground with someone who doesn’t share them. And remember, the fanatic “fears compromise and cannot be persuaded to qualify the certitude and righteousness of his holy cause.” This is one of the reasons that religious folks of this kind are so desperate to suppress dissent, or even probing questions: they cannot risk even considering that they may not be everything they have allowed themselves to believe.

This is, I suspect, at the heart of what's wrong with the ultra conservative/traditionalist ethos. This is why, as a group, these folks are obsessed with the kind of tabloid “gotcha” journalism and scandal reveling they’re increasingly associated with. Polarization suits them. Bad news is good for business, because it strengthens the dedication to the cause. By identifying and condemning the other, they think that in contrast, they define and elevate themselves.

Don’t get me wrong here — there’s a need to stake out moral positions, to condemn evils, and root out corruption. There is a real culture war. But when we place everything in terms of a conflict against hostile actors, we wind up losing ourselves to the conflict, and we generate little but scorn towards those outside the tribe. As Hoffer says, we must "warn, advise, urge, glorify, and denounce." These become our only real purpose. We act as though we are the immune system for our system of belief, searching for and destroying any ideological pathogens that threaten to infect it.

To return to the primary theme of fanaticism vs. creativity, I can’t imagine how to find art in this environment. And without art, we will never inspire; without inspiration, we’ll never change anything. You cannot persuade the non-fanatic to join your cause unless you can show him the truth, beauty, and goodness, it contains; but you cannot properly understand or convey truth, beauty, and goodness if your life is about little else except checking statutory boxes to the exclusion of love, creativity, and understanding.

A friend of mine put it rather brilliantly recently:

We've fallen into a kind of deconstructed concept of the Faith. We've erased all the other kinds of knowing and clung to propositional knowing, so when we say "I believe..." we mean exclusively intellectual adherence to particular creedal propositions, and never think that it might involve something more.

Whereas … before we had to respond to the Protestant revolution, we would say, "Credo..." and mean a great deal more than a mere intellectual assent. We would mean, "I love" and "I'm dedicated to" and "I prioritize." So now when people have some difficulty with this or that doctrinal proposition, it becomes an all or nothing thing.

[…]

[This] renders the religion of the God of Love into a loveless, lifeless set of creedal intellectual proposals. And it's the lovelessness that has crippled us. And turned Traditionalist Catholicism into a kind of ideology of intellect, with heavily fascistic overtones.

If there's no love, there has to be cops.

Love keeps order way better, but people don't like it because it's wild. It's untamed.

So in the absence of anything to offer other than the set of Creedal Proposals (along with the threats that back up adherence) they offer nothing but regulations and thought policing.

Traditionalists and conservatives, both in the religious and secular spheres, have demonstrated a profound lack of imagination. Everything is couched in theological terms. Everything we might find entertaining or interesting is strained like a gnat through the filter of our ideology. "Would Jesus watch that? Would Mary?"

Human tragedy and comedy and redemption arcs are messy. Cardinal Newman was right when he said it would be foolish to attempt a sinless literature about a sinful man. What might we be able to produce if we stopped trying to make Jesus video games and started making real art?

I'm not kidding about the Jesus video game, by the way. Someone actually thought this was a good idea:

All I can think of, watching that trailer, is Hank Hill's famous admonition:

Somehow, in reaction to a rapidly secularizing world, we've developed this weird, distorted theotropic response. We've become puritans. We use our boycotts as status symbols. We take so much pride in withdrawing from the world that we can't possibly hope to contribute something of value to it. The catacombs might be the place where we nurture our faith, but they're not where we stake a claim on the world.

If we think we’re going to successfully make art that matters again merely by creating characters, stories, or images that serve only as dogmatic sock puppets, without any ability to process real human emotion and drama, we’re fools. Almost everything we try to make these days is sanitized for our protection, which only leads to bland, uninteresting work that nobody outside the fully converted has an interest in — and often, not even they do.

Looking back at history, we see how many of the greatest artists of Christendom were in fact moral degenerates in many respects. Questions swirl around Michaelangelo’s sexuality. Bernini was an adulterer who arranged the mutilation of the face of his unfaithful mistress. DaVinci was accused of committing criminal sodomy as a youth, but the charges were dropped. Beethoven made use of prostitutes. Schubert — whose Mass in G was my first experience of true sacred music, and moved me to tears — is believed to have died of syphilis (and the toxic mercury used to treat the disease at the time) as a result of his profligacy. Examples abound of this sort of thing. It should be noted here that the most profound, critically acclaimed, and enduring piece of Christian art in the modern world is the film, The Passion of the Christ, which was conceived of, produced, co-written, and directed by Mel Gibson, one of the most compelling and yet clearly troubled artists in the world today.

I don’t understand, exactly, this relationship between those more given to moral digressions and the creation of art, but for a time, at least, the Church seemed to accept it, or at least not to allow it to be an impediment, and a symbiotic relationship between the Church and artists, however unorthodox, produced countless treasures still revered to this day.

Maybe it’s just that men who have suffered, fallen, and sinned have a different perspective on how the world works than those who haven’t do. Maybe it’s that bohemians and prodigals are less fanatical by nature, and thus more open to creativity and “fruitful intervals of groping” — grappling with the realities of the human experience in a broader spectrum, helping us to see the story of fallen man redeemed from the eyes of men not so sure about their own redemption, or more acutely aware of mercy and forgiveness.

Or maybe it’s none of the above, and something else entirely.

But we should really try to figure it out before we fade into complete obscurity.

Another dynamite essay, Steve, thank you. There's a lot to unpack and think about, as you said. Fanaticism is something I encountered a lot in my former career, and the literature I studied on the problem was directed to different ends obviously.

You make a lot of important points on your own I want to consider at length. I thought of a line from an old movie -- I think it was Sean Connery who said it -- "the line between faith and frenzy is all too brief."

My experiences in the field were that none of the fanatics I encountered were ever truly dedicated to something they had perfect confidence in. Nobody is fanatically shouting that the sun is going to rise and set tomorrow, for instance. "When people are fanatically dedicated to political or religious faiths or any other kinds of dogmas or goals, it's always because these dogmas or goals are in doubt."(R. Pirsig, ZAMM, 1970)

That was certainly true in my experiences in the Middle East, Ottawa, London, Paris, and Washington DC.

Brilliant. I just subscribed.