If God is Not, Is Everything Permissible?

If you struggle with belief, is it because you're secretly a moral monster?

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

I came across a Fulton Sheen meme today, and it got me to thinking. Here’s the meme:

Archbishop Sheen was a brilliant rhetorician, but he knew his audience, and that they would just eat up this idea.

But considered objectively, it’s unjust.

Catholicism tells us that faith is a gift, a supernatural virtue God gives as he wills. We can correspond to the gift, but we cannot summon it. “Blessed are you, Simon Barjona, because flesh and blood did not reveal this to you, but My Father who is in heaven." (Mt. 16:17)

People can't just manufacture faith.

St. Thomas argued that natural reason could lead us, via syllogistic thinking, to the understanding that God exists, but not WHO God is. (I’m not sure I agree with him, but that’s another post.)

As the Sheen quote above demonstrates, there is a theme in Catholic thought that if a person is an atheist, or an agnostic, it's because of some malice towards being beholden to moral authority, or some besetting sin. And while it's certainly true that an atheist or an agnostic is unlikely to concern himself with strict observance of the Church's precepts and moral law, it doesn't mean that he is an atheist or an agnostic because he is a moral monster.

About 12 years ago, I had a coworker who was a very intelligent and very intentional atheist. It was a small office, and he and I worked mostly alone in the same space. When we had downtime, we'd sometimes spar from our respective desks, him with his atheistic arguments, me with my Catholic ones. We seemed fairly evenly matched; he complimented me as the most capable apologist he'd met, I knew him to be probably my superior in intellect and logic. One time I asked him about the old Dostoyevskian proposition, “If God is not, then everything is permissible.”

“That’s not how it works, man.” He told me. “I still have people I love. I don’t want to hurt them. I have to function in a society, so I can’t murder or steal. There may not be eternal consequences for my choices, but there are consequences.”

For the longest time, I didn’t believe him. I thought it was impossible. If you weren’t going to get in trouble for what you did wrong in this life, it was party time.

Much later, when my own faith first started to slip through my fingers against my will — something I’ve had other Catholics tell me was impossible — I was afraid. I begged God to help me not to lose it. To help me to understand. To believe, to figure out how to love him, all of it. I still ask him for a lot of these things today, if less frequently, and less fervently. I’m not sure, after years of pleading with someone who never answers, if I’m just talking to myself.

When I hit a low point, living separated from my wife, trying to drink away the pain, not actively living a debauched life but also not making any effort within my limited circumstances to observe the precepts of the moral law, I thought I was sliding inexorably towards the exact kind of moral monster I always thought I was going to be without faith. Someone who sinned gravely, habitually, without compunction.

But then, something happened.

The conflict in our marriage, the anger with which I had habitually treated both my wife and children, the loneliness I felt, my pain-coping, self-deceiving mantra of, “It doesn’t matter, nothing matters,” all of it led to a decisive moment. A breaking point. A moment where things had gotten so bad, so out of hand, that they crystalized into an instant where there was a chance I could massively course-correct right then or lose everything that ostensibly mattered to me that very day.

The details of that moment and how I arrived there are personal, and I won’t share them here. They belong not just to me, but to the woman I gave my life to, love above all others, and whom I failed in so many ways. I am ashamed of how I arrived there, even if I can remember the excruciating path that brought me to it with a sense of false justification. I wonder how hard it would be for the me of today to convince the me back then that I was being a fool. Was my heart so hardened, my vision so blind, that I could not be made to see?

A night came when I knew, in a deeper way than I have ever felt, that I was losing her. I hadn’t been talking to God much at that time, but I spent the night in feverish, desperate prayer. On the day that followed, I found myself on my knees, sobbing, begging for forgiveness. And she, to her surprise, forgiving me, despite not being sure why, or what that would mean. She said she was done, and her change of heart was a miracle. I have wondered, if it was, why God never answered all the other times we had begged for one in our 17 years of marriage — years filled with fighting and turmoil and struggle we could not seem to overcome on our own.

Maybe it really was a miracle. Some of you are no doubt thinking that as you read this. That possibility is one of the things that keeps me from giving up entirely on belief. It’s certainly something I can’t explain. But if I’m being really honest, it’s also something I resent. When I imagine a conversation I might have (and have had) with God about it, I want to say: “All this time I begged for you to help, all this damage we did to each other and our children, all the far-reaching consequences of our inability to stop the constant ugly bickering, and you chose this moment, when things were this far gone, some broken in ways that can never be mended, to prove that you knew our efforts were insufficient and you could have fixed it all along?”

It almost feels like being taunted.

But my own misgivings aside, what I know is this: I changed that day.

When it really hit me what I was losing, what I had taken for granted, what I had failed to honor and uphold because I was just so tired of feeling hurt and rejected, I felt this overwhelming sense of, “Nothing else matters but the people you care most about. Not the Church, not the observance of religion, not the expectations of others on who you should be as a husband or father or man, only the way that your family them feel your love.”

That day, my rage, which had until then been a daily, unpredictable habit for my entire adult life, died down to little but cold embers. Previously, I could rarely make it a week or two without a huge blowup, no matter how many Communions or Confessions I made, no matter how many rosaries I prayed. I had battled other habitual sins, too, that no amount of tearful pleading before the Blessed Sacrament had helped me to curtail.

And then, just like that, I was able to stop.

Fear of God was never enough to keep me from my given sins. Love of God was never strong enough to move me away from them. But love of my wife, and children, who I very well could have lost? Nothing was worth that cost.

From an empirical standpoint, I do not believe it was the sacraments that helped me. I’d been away from Mass during COVID and had been observing the Sabbath from home, such as I could. My confessions had begun being further and further apart, and though I did go, right around the time I was forgiven, I’d also gone countless times over the preceding years with no similar effect. Later that year, even when I went to Mass a time or two, I didn’t receive Communion, because my anger at the Church, and at God, and my inability to accept certain required beliefs made me feel as though I could not in good conscience say I was in full communion.

But nevertheless the changes stuck. Oh, I’m far from done with the work I need to do to become a better man, but my kids no longer know me as the dad who blows up all the time. My relationship with my wife, though still healing, is healthier than it has ever been, and we have a new baby to show for it. Those habitual sins I couldn’t kick, no matter how frequent my confessions? I haven’t returned to them even once in the better part of two years.

And yet, even with COVID restrictions lifted, I’m no longer practicing. My faith is too damaged. My anger, which has gone from most other areas of my life, is still too intense when it comes to the Church. The toxicity of my experience of Catholicism, and all of its neuroticism-inducing effects, is all I can see.

What do I mean by this?

I wrote about this on social media last week, and I’m going to borrow from it here. I don’t know that I have a better way to explain it.

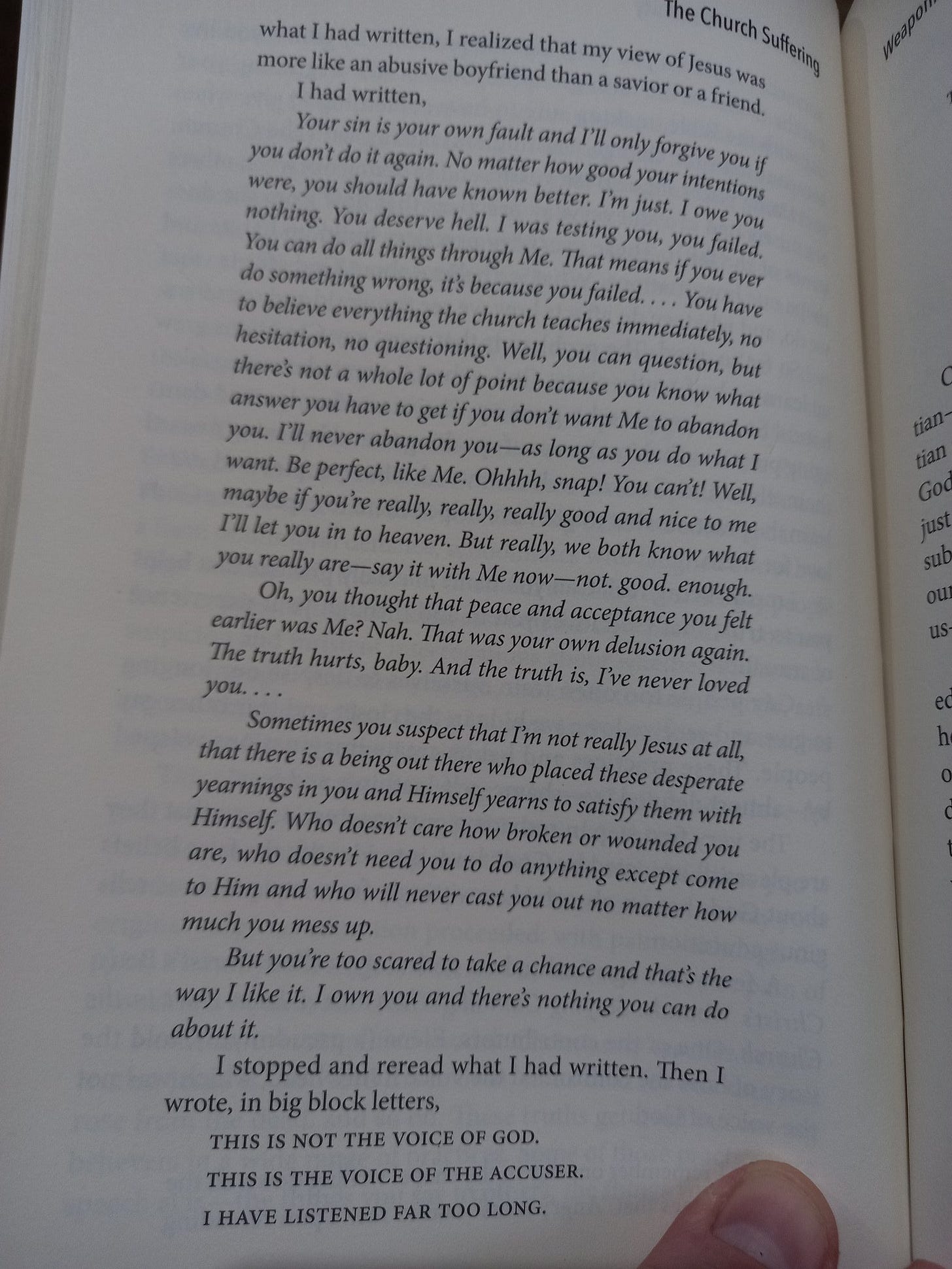

An online friend sent some images from a book he's reading in the hopes it would be helpful to me as I navigate the agita of my interminable existential crisis. This image sort of stopped me in my tracks:

So much of this mirrors my own constant thoughts, and the battle going on inside me. And that raises an interesting set of questions.

I feel as though concluding that these kinds of thoughts represents listening to "the voice of the accuser" is an obvious coping mechanism. It's the thing you have to tell yourself if you're desperate to keep believing.

But what if it's not the accuser, though?

What if the reason so many people have these exact thoughts is because it's the logical conclusion of some of the themes that are constantly reiterated in Christian faith, particularly Catholicism? What if it is the result of what I call the "Catholic beaten dog syndrome"?

I can't tell you how often, in my online discussions with other Catholics, I hear some variation of the phrase, "We deserve worse. We all deserve hell." Imagine hearing such a thing from a child. "We deserve worse than the beating dad gave us. We deserve death by his hand."

That'd be pretty chilling if you got that from a kid. You'd immediately be on the phone with the cops, or child protective services, or anyone you think could rescue them from what sounds like an abusive situation. But this is how so many of us have been taught the faith.

And this is a corollary to the idea that without the sacraments, without God, we automatically become moral monsters. It’s just not true.

Now you can make the argument that if we learned the faith that way, we learned wrong. That this isn't who God is. But many of the saints seem, in their writings, to reinforce the view that yes, he absolutely is.

I was certainly raised to see God as an omnipresent surveillance deity who was watching even when my mother wasn't, and would punish any misdeed I didn't get caught doing in this life. That and many other things in my upbringing made me deeply neurotic & scrupulous.

But I can't exactly just point the finger at my mom, who was my primary formator as a child, when you can find countless saints and catechetical materials that also pushed themes like this with greater and more terrifying zeal. My mom didn't make this stuff up.

What if these themes paint a portrait of a God we are told is pure love, but whose described actions signify cruelty? What if, when we are finally pushed to a breaking point where fear just doesn't work anymore, we start to see through the fog of all this imposed angst? To see it not as truth, but falsity?

Among other things, I honestly can't reconcile a loving God with the massa damnata — the notion that most people go to hell. This is huge for me. It's not possible. And the massa damnata forms so much of traditional Catholic spirituality & thought. Fear of hell and how many people go there is a big gun to your head. It was always, and remains to this day, the biggest reason I can’t simply let all of this go and get healthy without it. It’s why I obsess about it. It’s why I can’t stop talking about it. I could die of a heart attack tonight, or a car accident tomorrow.

And where would I go then, my honest and sincere questioning no longer mattering before my alleged particular judgment?

You may not believe it, but this stuff all gets to me so much that there was a time when I actually stopped hanging out with good friends more or less permanently after a conversation where they just couldn't accept that there's a lot of traditional Catholic thought indicating unbaptized babies are excluded from heaven.

I thought a "trad" had to stand that ground. This is what this stuff does to you.

And when we conclude, "Oh, the reason I'm thinking these awful thoughts is because I'm being duped by the devil," we're doing the same beaten dog thing that says "I deserve worse" every time we encounter suffering. We're saying "I cannot trust my own faulty reason."

This is a function of being told constantly that we are worthless on our own, that we can do nothing without God, that our reason is faulty, that we just have to have faith (or we'll be damned), that any problem with our understanding of faith is because we're fallen.

Which is why, in my view, it matters so much to have experiences like I have had, where I’ve overcome vices and sins without the clear help of sanctifying grace. It leads to a conclusion that, “Oh, wait, I actually can do some things on my own.”

As a Catholic, I’d be forced to see that as a bad thing. But as a human being, it’s freaking empowering.

So the way I view it, there are only a few possible conclusions:

All of this stuff we’ve had packed into our heads about our own worthlessness, guilt, inability to do anything good without God, and the notion that we deserve hell for merely existing as fallen human beings is part of a cruel lie that has extorted unthinkable amounts of time, effort, and money from the faithful over the centuries while exacting total control over their lives. It’s a human invention, and the God who would do all this is made up. The good news about option 1 is that what it represents can be safely disregarded.

God really is this way, we’re all screwed from conception because of sins we didn’t commit, and all of this points to God being as awful as this makes him seem. In this scenario, we'd be wise to treat him like Zeus or Odin - a divine tyrant whose occasional benevolence is outmatched only by his capricious wrath, which must be appeased if we wish to survive with a chance of escaping eternal torment. He may not be good, but we can’t escape him, and so we’d better do what he wants.

God isn't like this at all, but is in fact incredibly loving and merciful, does everything possible to avoid damning people, and is simply not the being portrayed by the historical Church.

Of these options, 3 is the most obviously appealing. But it's also a problem.

If 3 is correct, then what do we do with Catholicism and all of its claims? I don't mean whatever this post-conciliar ape of Catholicism is, with all of its attendant deviations and diminutions. That doesn’t demand much of anything of anyone, which is why only a small percentage of the people who are a part of it really even bother. I mean the traditional faith, where so many are turning for authenticity?

The historical Church, her historical teachings, and the writings of her saints and doctors cannot simply be discarded in favor of some new, ersatz, Catholic-Lite™ version that's been sanitized for our protection. That's not how it works. We have a choice between versions to make.

C.S. Lewis's "trilemma" comes to mind here:

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.

The way I see it, either the Catholic Church was and is the true religion founded by the Son of God, or else she is a monstrosity. You can shut her up as false and evil, but let's have no patronizing nonsense about her being merely mistaken. She makes too many demands, too many grandiose claims, and thus has not left that open to us.

And this is why I focus so much on her claims when I discuss faith. A Church that had said all along, "You know, we love Christ and we're gonna do our best but we'll get a lot of things wrong, even big things, and we'll course correct when needed" would not pose such a huge dilemma.

That’s not the Church we got.

Instead, we got a Church that claimed immense power, divine protection, total supremacy over both religion and the secular world, infallibility, indefectibility, and complete exclusivity over salvation. A Church that produced this infallible statement at the Council of Florence:

It firmly believes, professes, and proclaims that those not living within the Catholic Church, not only pagans, but also Jews and heretics and schismatics cannot become participants in eternal life, but will depart “into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels” [Matt. 25:41], unless before the end of life the same have been added to the flock; and that the unity of the ecclesiastical body is so strong that only to those remaining in it are the sacraments of the Church of benefit for salvation, and do fastings, almsgiving, and other functions of piety and exercises of Christian service produce eternal reward, and that no one, whatever almsgiving he has practiced, even if he has shed blood for the name of Christ, can be saved, unless he has remained in the bosom and unity of the Catholic Church.

Not even a martyr for Christ can go to heaven unless he has jumped through the proper bureaucratic hoops. That’s cold-blooded, I don’t care who you are.

The stakes are so damn high, for the Church to be wrong means the entire thing starts coming down like a building whose foundation has suddenly been obliterated.

At this point in my journey, I don’t know which conclusion is correct.

I do know that questions of faith or disbelief are not so simple, so cut and dried, as the late Archbishop Sheen would have us believe.

It’s not an open and shut case that if God is not, everything is permissible.

It’s possible for unbelievers to live a relatively moral life, because it benefits them and those they love to do so.

It’s possible for believers to be complete and utter shits, because their false sense of moral superiority derived from a totally unfalsifiable belief that they are righteous for checking all the right boxes justifies this in their petty minds.

It’s hard for me to say that a hedonistic atheist is a worse man than a prideful, judgmental believer. If Christianity is true, I’m not sure either has a path to eternal beatitude.

But I’d say a kind, loving, considerate atheist or agnostic is arguably a better man than a prideful, judgmental believer. An atheist who doesn’t steal from his family, or cheat on his wife, or beat his children is, at the very least, living a life of natural virtue that it actually behooves him to live.

Of course, if Christianity is true, the true saint — the believer who lives virtuously, with humility, with charity, with love, has the best shot of all.

I’m just not sure I actually know anyone like that. Because when push comes to shove, few of us are as good all the time or as bad all the time as we tend to believe.

I basically subscribed just so I could comment my support. (I’ve been following along free for some time.)

I have been through two major crises of faith in my life and they were both brutal. As an adolescent, I moved from cradle Catholic to a very liberal denomination of Christianity that wouldn’t qualify as Christian by most definitions, then two years ago I moved from my liberal denomination back to Catholicism. The second move involved the loss of many, many friends and my entire faith community, which I was deeply embedded in.

Anyway I have a lot of specific thoughts on doctrine blah blah blah blah blah (my favorite writer on most of the sorts of issues you raise is Larry Chapp over on his blog Gaudium et Spes 22), but honestly I just wanted to comment to say that Fulton Sheen can go pound sand.

Despite—hey, maybe partially because of—the fact that I disagree with you on just about everything, I think you are one of the most morally courageous writers I have ever encountered. It takes *a lot* to risk—and lose—as much as you have done for the sake of goodness and truth. Faith can *absolutely* shatter without our consent. Many of the best people I know either struggle with faith or lack faith entirely. Few (although some, to be sure) of the best people I know are devoutly practicing Catholics.

I think the love we have for the people right in front of us is the fullest and most important expression of the love of God for us, and ours for God. I think your revelation about your love for your family is part of that. This is very far from being a moral monster; quite the opposite. Despite my experience with crises of faith I don’t think I’m a particularly qualified advice giver but I guess I do feel qualified to say that clinging to that love of your family, and learning to love them better and better, is probably the best thing for you to be doing. I’ll shut up now. Your posts are just so raw that it was impossible not to want to try to say something comforting.

tl;dr you’re not a monster and I don’t believe in a God who would say you are.

More great stuff Steve, I have two thoughts, 1.) The Fear of everyone going to hell, and the dragging out of crazy quotes from saints (which are undoubtedly wrong) is a real thing in trad community’s, and I think the reason is, those folks are rightfully worried that the Church threw the baby out with the bath water, but no one in the trad communities will acknowledge is there was massive amounts of bath water that needed to be thrown out. They feel every concession is an afront to the true faith, which is plainly wrong. 2.) I think you did get some answered prayers, and from what I’ve watched from afar, a lot of the reason may have been that your old job wasn’t good for you, which is a huge problem for a lot of men