Indifferentism, Infallibility, and Other Nonsense

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

I’ve been trying to stay away from Catholic commentary, but there’s a story that keeps coming across my social feeds, and I can’t let it pass without comment.

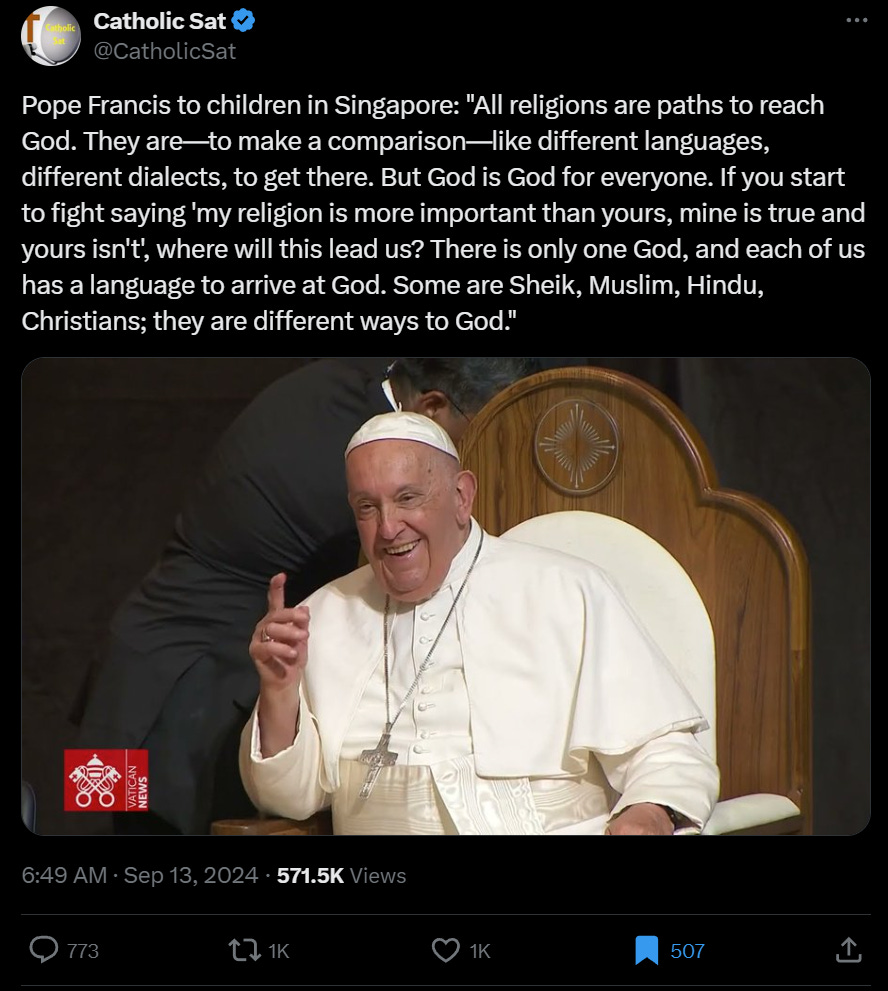

Here’s the setup:

This, of course, is getting lots of negative attention among orthodox Catholics. Indifferentism is, as a number of them are noting, a heresy.

Not too long ago, I would have been among the first to grab a torch and a pitchfork and prosecute these scandalous remarks!

In fact, almost a decade ago, I wrote an article about Francis’s dalliances in this regard, entitled, Why We Can’t Be Indifferent to Indifferentism.

Here’s my opener:

Why does it matter if people convert to Catholicism? Isn’t being Methodist good enough? Is a lapsed Catholic — a part of our religion by baptism — beyond hope? What about a nominal Christian who believes in doing good, even though she rarely darkens the doorstep of a church? And what about all those of other faiths – Hindis, Buddhists, Jews, Muslims, and so on?

The answer to the question is simple: yes, it matters; more than anything else in this life. Though you don’t often hear it expressed in such clear language these days, the Catholic Faith is the True Faith, the one Church established by Christ for the remission of sins and the salvation of souls. We profess as much in the Creed, when we say that we believe in “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” and when we “confess one baptism for the remission of sins.” One Church. One Baptism. Not many. Without these, there can be no salvation.

I went on to cite scriptures and papal documents like Unam Sanctam and the writings of great saints, backing the premise that “Outside the [Catholic] Church, there is no Salvation.”

My goal was to try to counter these kinds of statements from Francis, who has been uttering them for his entire pontificate.

In an ironic twist, these endless Bergoglian heresies and scandals ultimately unraveled my ability to believe in papal infallibility. Having come to “obstinately” (ie., “unable to believe no matter how much you threaten me”) doubt one Catholic dogma, the belief in which is allegedly necessary for salvation, I lost confidence in all Catholic dogmas. If one could so obviously be wrong, why should I trust any of them?

As I explained elsewhere this morning:

Papal infallibility was my personal silver bullet. It was the thing that unraveled everything else. Not just because it’s useless and tautological at best, but because it pretends to protect against this very thing (see below) until tested. To make such nonsense a dogma & have a pope like this? Woof.

And don’t even start with “it isn’t ex cathedra.” If it has to be ex cathedra — which most theologians agree has almost never been used — then it’s utterly worthless.

You can’t call it “infallibility” and then have the pope be the main guy spreading fallible, false, heretical ideas. You can’t teach Catholics that he can’t err in faith and morals and have him do exactly that, every day.

As I became increasingly convinced that papal infallibility couldn’t even be real, let alone a required belief for salvation, I wound up in the awkward position of moving from apologist to critic.

And so began my deconstruction process, which started with this singular dogma but wound up questioning everything else as well. At the end of that road, I found myself facing more fundamental soteriological dilemmas. The biggest of these was my growing sense that the only salvific belief that would validate the supposed omnibenevolence of God taught by Christianity would be…universalism.

There is simply too much left in doubt about the supernatural world for us mere mortals to make sufficiently informed and culpable decisions so as to determine our eternal fates. Multiple world religions (and some offshoots) claim exclusivity of membership as necessary for salvation, but none can prove that they are the True Path™. And in any case, a God who truly loves every soul he creates infinitely and desires its salvation would not allow the vast majority of creation to perish in the fires of hell, as most of the Christian tradition and many of the greatest saints have asserted.

And yet “the fewness of the saved is scriptural,” Massa damnata is the consensus position across the history of Christian religion, and the exclusion of not just non-Christians but non-Catholics from salvation has been codified in the most authoritative terms, perhaps most fervently by Pope Eugene IV at the Council of Florence:

The sacrosanct Roman Church, founded by the voice of our Lord and Savior…firmly believes, professes, and proclaims that those not living within the Catholic Church, not only pagans, but also Jews and heretics and schismatics cannot become participants in eternal life, but will depart “into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels” [Matt. 25:41], unless before the end of life the same have been added to the flock; and that the unity of the ecclesiastical body is so strong that only to those remaining in it are the sacraments of the Church of benefit for salvation, and do fastings, almsgiving, and other functions of piety and exercises of Christian service produce eternal reward, and that no one, whatever almsgiving he has practiced, even if he has shed blood for the name of Christ, can be saved, unless he has remained in the bosom and unity of the Catholic Church.

As David Bentley Hart so adroitly explains in That All Shall Be Saved:

This is not a complicated issue, it seems to me: The eternal perdition—the eternal suffering—of any soul would be an abominable tragedy, and therefore a profound natural evil; this much is stated quite clearly by scripture, in asserting that God “intends all human beings to be saved and to come to a full knowledge of truth” (1 Timothy 2:4). A natural evil, however, becomes a moral evil precisely to the degree that it is the positive intention, even if only conditionally, of a rational will. God could not, then, directly intend a soul’s ultimate destruction, or even intend that a soul bring about its own destruction, without positively willing the evil end as an evil end; such a result could not possibly be comprised within the ends purposed by a truly good will (in any sense of the word “good” intelligible to us). Yet, if both the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo and that of eternal damnation are true, that very evil is indeed already comprised within the positive intentions and dispositions of God. No refuge is offered here by some specious distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent wills—between, that is, his universal will for creation apart from the fall and his particular will regarding each creature in consequence of the fall. Under the canopy of God’s omnipotence and omniscience, the consequent is already wholly virtually present in the antecedent.

Nor, for the same reason, does it help here to draw a distinction between evils that are positively willed and evils that are providentially permitted for the sake of some greater good. A greater good is by definition a conditional and therefore relative good; its conditions are already and inalienably part of its positive content.

Moreover, in this case, the evil by which this putative good has been accomplished must be accounted an eternally present condition within that good, since an endless punishment is—at least for the soul that experiences it—an end intended in itself. This evil, then, must remain forever the “other side” of whatever good it might help to bring about. So, while we may no doubt hope that some limited good will emerge from the cosmic drama, one that is somehow preponderant over the evil, limited it must forever remain; at such an unspeakable and irrecuperable cost, it can be at best only a tragically ambiguous good. This is the price of creation, it would seem. God, on this view, has “made a bargain” with a natural evil. He has willed the tragedy, not just as a transient dissonance within creation’s goodness, leading ultimately to a soul’s correction, but as that irreducible quantum of eternal loss that, however small in relation to the whole, still reduces all else to a merely relative value.

What then, we might well ask, does this make of the story of salvation—of its cost? What would any damned soul be, after all, as enfolded within the eternal will of God, other than a price settled upon by God with his own power, an oblation willingly exchanged for a finite benefit—the lamb slain from the foundation of the world? And is hell not then the innermost secret of heaven, its sacrificial heart? And what then is God’s moral nature, inasmuch as the moral character of any intended final cause must include within its calculus what one is willing to sacrifice to achieve that end; and, if the “acceptable” price is the eternal torment of a rational nature, what room remains for any moral analogy comprehensible within finite terms? After all, the economics of the exchange is as monstrous as it is exact.

I wrote, in the above-cited piece on indifferentism:

Love does not mean unconditional acceptance. It means desiring the good of another, even when they themselves have turned away from it. It means telling someone that they’re doing something that is hurting them, even when they don’t want to hear it. It means dying for the faith rather than compromising it. It means judging acts (but not souls) and offering fraternal correction, in order to help others to avoid eternal judgment.

The problem with our current approach to ecumenism and interfaith dialogue is that they amount to religious indifferentism, leaving us complacent in the idea that others are fine where they are, and can get to heaven through natural virtue and partial truth, but without conversion. Such thinking is tragically wrong, and inevitably stifles the zeal for souls that leads to evangelization.

What I would say to the younger version of me who wrote this is:

Don’t you see that your entire faith is predicated on fear? Fear of hell, fear of losing the state of grace, fear of God’s implacable wrath against you or your loved ones? Don’t you see that you are not so much driven by “zeal” to save souls from the devil, but from God, whom you fear far more? You are so worried that if you don’t get people to think “correctly” and believe “correctly” and act “correctly” according to these religious mandates even you struggle to believe that they will suffer horribly for failing to do so. You have the kind of messiah complex an oldest child has who has to protect younger siblings from abusive parents. You’ll do anything you can to keep them from making themselves an unwitting target of paternal rage.

For me — and I would argue for most Catholics raised within a catechetical, doctrinally-orthodox milieu — Catholicism is nothing if it’s not about the institution, the rules, and the clergy. Be obedient, be docile, be humble, resign yourself to suffering, do these things, don’t do those things, pray like this, worship like this, receive like this, this is reverent, this is irreverent, this is pious, this is sacrilegious, etc., etc., ad infinitum.

But taken logically, all of it leads to (or reinforces) these underlying fears:

God is watching, he is angry, and you’d better do something to assuage him. You don’t deserve him, he owes you nothing, look at all he’s done for you, you’d better grovel. Oh, but also he loves you so much, but then again remember if you eat that burger on a Friday of Lent or skip Mass on a Sunday and then and die in a car accident on your way home from lunch, he’ll send you to hell forever.

You’re so busy trying to keep your own ass (and those of the people you love) out of the fire, you’ve got precious little time to figure out whether you actually believe in a loving God whom you would find lovable.

People who grow up in emotionally or physically abusive homes often find that they can get into relationships but have no idea how to give or receive love. When your religion is just an echo of that same abusive dynamic, it deepens a sense of desiring but never feeling deserving of love, and knowing that the object of your intended love may very well turn on you in a heartbeat.

You are never safe.

If God is real, I struggle to see how he is loving or personal, inasmuch as we have all these religions warring over a mutually exclusive claim about who has the One Weird Trick that will get you to heaven, and God does nothing to clarify which one is correct. Countless people who want to believe and ask God for faith get no answer, which also undermines the idea of his omnibenevolence. (This is the Divine Hiddenness Argument in a very compressed nutshell.)

But let’s say he is perhaps one step removed. Benevolent but relatively indifferent. Non-hostile but non-helpful. Undeniable but personally inscrutable.

Wouldn’t it then be the case that every religion that seeks to understand him would be a path in his direction? Granted, it wouldn’t get you very far, and the particulars would still clash from religion to religion, but they’d all be chasing down a deeper truth to a greater or lesser degree.

This, too, feels like a mediocre explanation.

It’s simpler to believe that God isn’t real, particularly when you can’t seem to find any actual evidence for him (and especially not for these very exclusive and specific faith-based claims about him).

I like the idea of a God who lets us all find our own way to him by different paths. If he’s going to be mysterious and intangible, it would seem he’d at least give us a wide latitude for error in our attempts at discovery. It just seems so incredibly odd that a God who would care enough to want us to find him wouldn’t make finding him a whole lot easier. For those who might object that all they need to do that are the scriptures or the sacraments, I respectfully disagree. Those things act to affirm existing belief through repetition, authority, and the imagined effects of graces that can be neither seen nor measured. If there is more than a placebo effect at work, it would be very difficult to prove it.

Of course, a God who doesn’t care which religious path one takes sets up other problems, too. For example, it’s very difficult to establish a functional civic order without a singular religious framework to anchor it — I’ll talk about that a bit more in a separate piece. Suffice to say that none of the American founders really envisioned what pluralism would like a few hundred years later. It’s not really working out.

To sum up, Francis is, in my opinion, actually espousing the better belief in this case. That said, it’s one that is all but impossible to reconcile with the perennial teaching he ostensibly has the responsibility to guard and protect. Those who say it’s a heresy aren’t wrong, in a technical sense. And yet the fact that this is a heresy is a damning indictment of the orthodox teaching.

Once you believe the Church can be wrong when she insists that she’s right, all bets are off.

It’s very weird for me to recognize that disagreeing with Francis and seeing the way he undermined the teaching on the papacy ultimately led me out of the faith, only for me to turn around and agree with him because I no longer feel obligated to “uphold the teaching.” Don’t get me wrong: I don’t believe he’s a good man, or that what he is saying is reconcilable with Christianity as we understand it. But neither is the eschatology/soteriology taught in orthodox Christian schools reconcilable with the loving, just, good God they purport to believe in.

It’s a paradox that can’t be resolved easily.

Interestingly, the Pope's articulation has a name: perennialism. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perennial_philosophy

The problem is that the various "paths" don't really work unless you actually believe in the path you are on, and are not just behaving instrumentally (ie, "I go to church because it's good for community, but I don't believe any of it" type of thing). And the beliefs of all of them differ quite a bit, and many of them have uncharitable things to say (or have done in the not distant past) about other religions, generally or specifically, which makes it hard to actually be a perennialist and a believer, in the full sense, in any one of the "paths". This is why I think many people who have that kind of perspective end up as UUs, because that is a form of religion in which they are not actually within a "path" (at least not one of the historical ones, which is what perennialism is about) but are trying to straddle them ... perennialists generally took a dim view of that kind of synthetic spirituality, but it seems to me that you can't really be both a perennialist and a true believer in one of the paths -- it's contradictory.

---

On universalism, it's an interesting argument. I have been troubled about this at times as well, but it has never been my main trouble.

My main trouble has always been the knot of theodicy coupled with omniscience and omnipotence, and the way the Book of Job "handles" this. Hart deals with this, in typical fashion for him, as an aside in the text you quote:

"No refuge is offered here by some specious distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent wills—between, that is, his universal will for creation apart from the fall and his particular will regarding each creature in consequence of the fall. Under the canopy of God’s omnipotence and omniscience, the consequent is already wholly virtually present in the antecedent."

Yes. Hart here is talking about how you can't separate God's generally benevolent will from his will for a specific person. A similar issue arises regarding theodicy itself, namely: an omniscient God would, when deciding to create creatures with free will and moral agency, at the very least know all of the potential outcomes of that, and the probabilities for them. One of the most common rejoinders to the problem of theodicy is that God granted wide moral agency in order to permit the possibility of choosing love, but this raises similar questions to what Hart is doing with respect to hell, namely what conception of morality could ever justify knowingly creating the possibility of Auschwitz (and knowing that it was a possibility, as well as the probability of it coming to pass) as a necessary potentiality to permit the choice to love? Certainly no conception of morality that I am aware of. As we know, the Book of Job's response to this problem is "the answer is above your paygrade, because you don't have the entire picture, only I, God, do" ... but is that really a satisfactory answer?

It seems to me that this kind of question has never really been satisfactorily answered -- answers have been given, but they all have a lot of problems.

Does that mean it's impossible to believe in God? No, I don't think so. I do think it means that there is much more mystery than cut-and-dried when it comes to God than we may prefer to think, or at least than many religious believers, of any of the various Christian denominations at least, would prefer to think most of the time. There's a lot of things that don't make a lot of sense, and that's where the faith part comes in.

Like Jeremy, I have more issues believing the universe is solely material and just spontaneously came into existence, or is itself eternal, than I do believing that there is a force behind it all. The extent to which any religion actually understands what that is, is an open question, it seems to me. But, even so, many of us can still benefit from belonging to a faith tradition, not instrumentally, but believing as we are able, despite seeing the problems and contradictions. It very much depends on one's own experiences and makeup. I do relate to your own struggles here quite a bit, as someone who grew up Catholic (12 years of Catholic school), even though my family, while practicing, was never particularly pious outside of obligations -- I still get the culture and the challenges it raises for many people.

I never understood why almost all of the pressure or responsibility is on the lost, broken, blind sheep to find the True loving Shepherd. That seems backwards to me.