Kenneth Darlington is a Bellwether

Public empathy for a man who has had enough is an indicator of where things are

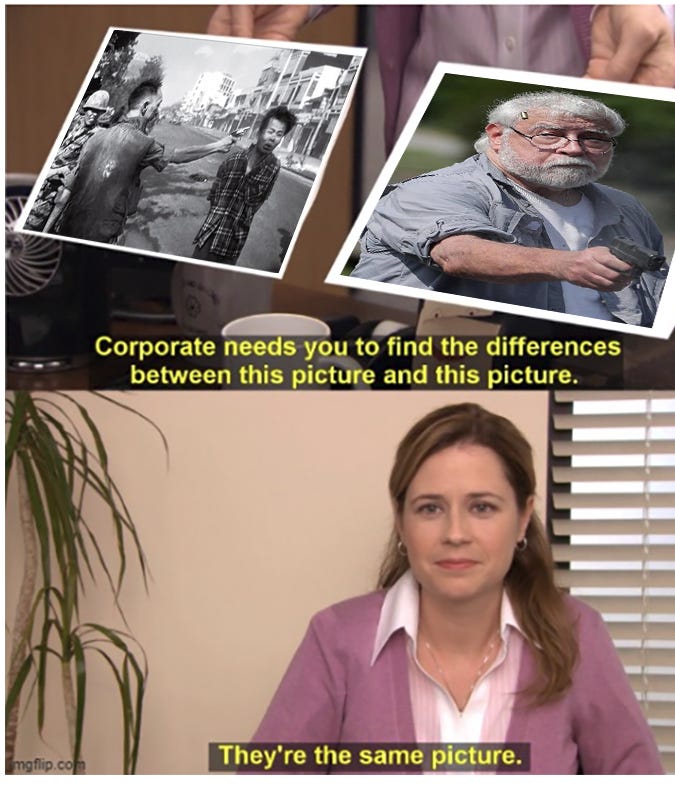

There’s a photograph making the rounds today. The clarity of the image is jarring. A moment of fatal violence frozen in the act. It shows an older man in a rumpled gray fishing shirt with roll-up tabs over a worn out white undershirt. The man holds a semi-automatic pistol in his hand, his finger squeezing the trigger. A haze of smoke surrounds the weapon. A single bullet casing gleams in the sunlight, frozen in the air in the middle of its ejection arc, next to the man’s right temple. His hair is white and tousled; his beard white and neatly trimmed. He looks dead-eyed and implacable through his glasses at his target, his mouth twisted up ever so slightly into an expression of resignation.

He does not look angry.

He barely even looks annoyed.

He simply looks like a man who has had enough, and no longer cares about the consequences.

The man’s name is Kenneth Darlington, and this week, he killed two climate protestors who were blocking the Pan-American highway after they refused to move.

Kenneth Darlington is a bellwether.

News reports say these particular protestors on this particular road — the Pan-American highway that connects Panama to the rest of Central America — “have caused up to £70million in daily losses to businesses and schools have been shut for more than a week across the country.” Evidently, they’ve been going on for weeks, and elsewhere “a demonstrator was run over and killed on November 1 by someone attempting to cross a roadblock during a protest in the west of the country. A fourth protester was also killed.”

There is a moment, in one of the videos taken of the event, where you can see Darlington switch from attempted negotiation to a shrug that clearly indicates, “Fine. If you want to do it the hard way, we’ll do it the hard way.” An instant later, his hand emerges from his pocket with a pistol, and he begins escalating his demands. None of the video clips I’ve seen have audible dialogue, and the conversation is presumably in Spanish, so I cannot do more than guess about what is being said.

Although the scene is modern and the context is entirely different, the moment is somehow iconic and immediately redolent of another famous photograph of a man with a gun.

Saigon Execution

Eddie Adams was an American Marine combat photographer turned photojournalist who was covering the Vietnam War for the Associated Press. During the Tet Offensive in 1968, as Adams was making his way up a street in Saigon, he saw the local chief of police, General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan, point his .38 at the head of a prisoner who had already been arrested and cuffed. The prisoner, a member of the Vietcong named Nguyễn Văn Lém, was accused of having murdered a South Vietnamese Liuetenant Colonel and his family, including his wife, mother, and six of his seven children.

Adams didn’t know the backstory on any of this when he raised his 35mm camera to take a picture of the scene that was unfolding before him. He also didn’t know that that the family that Lém had allegedly just killed was that of a friend of Loan, or the Loan was actually going to pull the trigger. But he captured the moment anyway, and the world will never forget.

The photograph froze the moment the bullet exited Lém’s head, his face contorted from the impact. It was an image of summary justice, brutal and succinct. It made its way to the front page of newspapers everywhere, and the sheer unabashed violence of it turned American sentiment definitively against a war they never fully supported. In a New York Times article on the 50th anniversary of the photograph and the event it captured, politics reporter Maggie Astor explained the cultural ripple effects of that one image:

It was a shocking sight for Americans, who had been assured by President Lyndon B. Johnson and his top general in Vietnam, William C. Westmoreland, that the enemy was on its last legs.

Meredith H. Lair, a Vietnam War expert at George Mason University, said the offensive “caused people to question whether they’d been fed lies by the administration, and to question whether the war was going as well as they’d been led to believe, and to question whether the war could be won if the enemy was supposed to be cowed and appeared so strong and invigorated.”

If the broader Tet offensive revealed chaos where the government was trying to project control, Adams’s photo made people question whether the United States was fighting for a just cause. Together, they undermined the argument for the war on two fronts, leading many Americans to conclude not only that it could not be won, but also that, perhaps, it shouldn’t be.

The photo “fed into a developing narrative in the wake of the Tet offensive that the Vietnam War was looking more and more like an unwinnable war,” said Robert J. McMahon, a historian at the Ohio State University. “And I think more people began to question whether we were, in fact, the good guys in the war or not.”

A police chief had fired a bullet, point-blank, into the head of a handcuffed man, in likely violation of the Geneva Conventions. And the official was not a Communist, but a member of South Vietnam’s government, the ally of the United States.

“It raised a different kind of question to Americans than whether or not the war was winnable,” said Christian G. Appy, a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. “It really introduced a set of moral questions that would increasingly shape debate about the Vietnam War: Is our presence in Vietnam legitimate or just, and are we conducting the war in a way that is moral?”

Adams himself, who won some 500 photojournalism awards over the course of a 45-year career, saw his legacy defined by the potency of that singular photograph. In a short reflection entitled, “Eulogy,” at Time Magazine — which listed his photo as one of the 100 most influential photographs of all time — he wrote:

I won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for a photograph of one man shooting another. Two people died in that photograph: the recipient of the bullet and GENERAL NGUYEN NGOC LOAN. The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world. People believe them, but photographs do lie, even without manipulation. They are only half-truths. What the photograph didn't say was, "What would you do if you were the general at that time and place on that hot day, and you caught the so-called bad guy after he blew away one, two or three American soldiers?" General Loan was what you would call a real warrior, admired by his troops. I'm not saying what he did was right, but you have to put yourself in his position. The photograph also doesn't say that the general devoted much of his time trying to get hospitals built in Vietnam for war casualties. This picture really messed up his life. He never blamed me. He told me if I hadn't taken the picture, someone else would have, but I've felt bad for him and his family for a long time. I had kept in contact with him; the last time we spoke was about six months ago, when he was very ill. I sent flowers when I heard that he had died and wrote, "I'm sorry. There are tears in my eyes."

I don’t remember for certain the first time I saw the photograph now known as “Saigon Execution.” It was likely in a special edition of Time Magazine’s most influential photographs I found at my grandmother’s house when I was a boy. It’s an image that has always stayed with me.

And today, when I saw the photo of Darlington, with the bullet casing soaring past his head as he stares, emotionless, at his victim, I was left with an eerily similar feeling.

As the meme says, “they’re the same picture.”

I don’t know who the photographer of the Darlington photo is, or if they’ll receive critical acclaim for their uncanny shot. It’s early, yet, in the life of this image, and it’s not the 1960s. We’re drowning in imagery, much of it violent, little of it leaving the kind of lasting impression that photos from the front lines did decades ago.

But the initial reactions to the Darlington photo are, I think, the most telling indicator of its cultural import. If “Saigon Execution” turned a nation against a failed war, the responses to “Panamanian Execution” tells the story of a world that has already turned against a system that allows bullies and self-styled victims and corrupt politicians and insane ideologies run roughshod over the normal, everyday people just trying to get by. It shows a man who seemingly embodies the ethos of Bill "D-Fens" Foster, the everyman-pushed-too-far antihero played by Michael Douglas in the 1993 film, Falling Down.

Let me be clear, even though I know it’ll be missed by many who read this: WHAT DARLINGTON DID WAS WRONG. I am not looking to valorize him, I am looking to contextualize him.

Darlington is an inkblot test. We don’t know enough about him or his motivations to say with any semblance of clarity why he did what he did. He could be a straight up, old-school hitman for all I know.

What matters here, for our purposes, is what the thing he did absent any of that information makes us feel.

For many, however much they may not want to say it out loud, that feeling was something like, “Finally. Someone stopped playing by the rules and letting these idiots walk all over him and took matters into his own hands. They should have cleared the road. He sent a message that needed to be sent long ago. You can’t just walk all over people and expect them to do nothing about it indefinitely.”

If you felt something this — and I certainly did — that doesn’t make you a murderer, or even a murder-sympathizer. It makes you a normal human being who senses innately and deeply that your rights have been being trampled on for a long time, and the rule of law is NOT on your side in trying to fix it.

I wouldn’t have shot those people, nor would you. I do not — at all — want these men to be dead. But I also absolutely do not want anyone like them blocking any road, or destroying priceless art, or on my lawn, or in my face, or at my kid’s school, or bothering me or my family in any way. And I absolutely want them to understand that the things they are doing will not be tolerated.

People ignore or dismiss the significance of the public reaction to what this man did at their own peril. If we are not careful, much larger segments of our declining society may follow in his footsteps. Men with nothing to lose should not be provoked. Create an entire society of men with nothing to lose, and you’ve got a powderkeg.

Something in Darlington’s expression, in the nonchalance of his violence, has created a deep, uncomfortable resonance in the minds of many people who have also had enough.

Enough of the exorbitant cost of groceries and gas and rent and mortgage and car payments. Enough of feeling like their kids are being indoctrinated and brainwashed by an education system and culture hell-bent on upending decency and traditional values and even reality itself. Folks who have had enough of living in fear that if they speak up on controversial issues that affect them and their families like crime and immigration and jobs and college admissions and affirmative action and gender identity issues, they’ll be unfairly labeled a racist or a “phobe” and get cancelled online and likely lose their jobs in real life.

It captures the mood of people who have lost faith in both experts and institutions, who have lived under the moral busybody tyranny of a medical and public health establishment that tried to coerce them into taking an unproven vaccine with untested side effects - or else. People who watch every day as new surveillance footage emerges of people robbing stores or committing random, savage attacks on innocenet people in places where nobody is allowed to stop them, where police do nothing in the face of violent mobs, or see protestors line their streets cheering on the genocide of an entire nation while their Jewish neighbors or their children are forced, once again, to hide in attics. People who have to dodge the zombie-like, drug addicted homeless people who overrun their cities, or find men who identify as women exposing themselves in public locker rooms with their wives or daughters, or men who identify as women doing the same thing on their daughters’ sports teams, or raping their daughters at school, but they’re not supposed to say anything about any of it, because again, they’ll be labeled a “bigot” or a “transphobe” and shunned or harassed.

It touches a nerve with those who believe, with good reason, that the electoral system is rigged, that fraud and manipulation are the hallmarks of our “democracy,” and that the outcomes of political races are pre-determined by shadowy interests. People who are tired of being lied to, to their faces, about transparent political agendas to protect politicians who are caught red-handed committing crimes if they hold the “correct” political views, but also to destroy those who don’t:

People who are disgusted by the bloodthirsty demand for lax abortion policies on the part of their neighbors and colleagues, who don’t want their children drafted to fight in someone else’s pointless war, who are sick and tired of everything in the culture being oversexualized and designed to ideologically capture their kids or preach at them from a perspective that undermines their fundamental values, and at least a dozen other things I haven’t mentioned besides.

People who wind up stuck in traffic because of the idle rich protesting “Big Oil” who have nothing better to do than block their commute to the job that’s allowing them to barely scrape by, or the route to get their pregnant wife to the hospital to deliver their baby.

People who are sick to damn death of feeling like everything is going to hell in a handbasket and there is nothing they can do about it.

Powerlessness, hopelessness, lawlessness, unmitigated corruption, living every day struggling to get by while under endless ideological siege — these are the things that drive otherwise good and decent people to snap. These are the solvents that break down societal cohesion and reduce people to tribal barbarism.

A Symbol, Not a Hero

The question, “Who is Kenneth Darlington” has few solid answers thus far. He appears to be a 77 year-old retired lawyer and professor, who was born in Peru, has been living in Peru, but holds dual citizenship in both Peru and the United States. Prior to today, there’s not a lot of information about him easily accessible online. He had a legal profile on the website Martindale.com, which has been hastily scrubbed. The cached version is still available, at least for now:

His LinkedIn profile is little more than a placeholder. He shows up in some old Spanish-language news stories for an arrest back in 2005, for weapons possession. He was released on bail. At the time, he was mentioned as having been a spokesman for Marc Harris, an American CPA who ran a financial services group in Panama that engaged in fraud and money laundering. Harris was tried and sentenced to 17 years in jail, of which he served 13 before being released.

It’s difficult to know much else about the man. He’s been living in Panama, almost certainly completely offline, which makes the headlines saying he’s an “American” a bit of a comical overreach in an attempt to associate him with America’s gun culture. His previous arrest for weapons possession nearly 20 years ago also happened in Panama. He may be, for all we know, a bush-league player in organized crime. He is hardly a good old boy from the back country of the deep south.

But then, neither were Mark and Patricia McCloskey, two wealthy Missouri attorneys who sought to defend themselves and their home against a trespassing mob of “Black Lives Matter” protestors by standing on the lawn holding drawn weapons, demanding that the trespassers leave. For exercising their Constitutional rights, they were prosecuted and had their law licenses suspended, while none of the trespassers were even charged.

Over and over, the public is told that the good guys will be punished and the bad guys will go free. Men like Daniel Penny, the former Marine who stopped Jordan Neely, a frequently-arrested-and-released (42 times!) homeless man acting erratically and threatening people on a New York Subway. Penny subdued Neely by placing him in a chokehold, accidentally killing him. Although he did not believe he was killing Neely, asked bystanders to call emergency services during the struggle, and put Neely in a “recovery position” after he fell into unconsciousness, Penny still ended up charged with manslaughter.

"I was scared for myself but I looked around there were women and children, he was yelling in their faces saying these threats. I just couldn't sit still,” Penny said. Witnesses testified that they were in fear. The case has not yet gone to trial, but if Penny is convicted, what signal does it send to other good Samaritans who want to help protect the vulnerable from these threats?

I’ll tell you the message it sends: it doesn’t matter if you think the law is on your side, or you try to do the right thing, or you only want to protect your life, your family, or the lives of other innocents. They will come for you anyway.

And this is why some people are seeing Kenneth Darlington as a “hero.” Because they’re not willing to take any more. Because he’s a man who finally pushed back against the insanity in definitive terms. Because he clearly didn’t care what the consequences were, he just wasn’t going to play the game anymore.

Even among those who don’t condone what he did, many still find themselves identifying with why he did it:

These are just a few examples. If you search social media, you’ll find hundreds more.

Obviously, not everyone is empathetic. But many are. Overall, the sentiment I think I’ve seen most is a kind of unsurprised resignation: “Something like this was bound to happen,” they say, or “It was only a matter of time.” Expressions like this come up in quite a number of public comments.

People just sense it. They know that everyone has been pushed too far, and that at any moment, they could be the next one to have a “TMFINR” moment and lose their crap.

There is a zeitgeistian consensus that things have got to change, or more bad things are coming, and it won’t just be a few. Unrest is building.

Kenneth Darlington is a bellwether. A wake-up call. Sadly, he is one we almost certainly will not heed until it’s far too late.