Many Masks: The Stories We Tell Ourselves About God

Questioning our theological narratives is not the same as questioning the divine.

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

I saw a post on X that got me thinking.

Many of my more religious followers will likely find it odd, but I am marking it down here as a curiosity point worthy of some exploratory thinking; make of it what you will. It comes from a guy named Jason Wilde:

I’ve been sitting with this for a long time. The more I read, the more I travel through the old texts, the more I listen to what people say they’ve seen in prayer, meditation, or crisis, the more obvious it becomes. I think we’re looking at the same story wearing different masks. The names change, the language shifts, the art styles morph, but behind all of it is the same presence, the same pattern...contact.

Think about what Krishna tells Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita that “Behold, Arjuna, thousands upon thousands of my divine forms… but with these eyes you cannot see Me.” And then, when Krishna grants him the “divine sight,” Arjuna freaks out. “O Lord,” he says, “I see You everywhere, of infinite form… I can’t bear this.” This is a record of a human being given a glimpse of something so weird he begged for it to stop. The same thing happens to Moses “no one may see my face and live”, and to Ezekiel, who ends up babbling about wheels within wheels covered in eyes. Different continents, same story. The answer is always the same... “You couldn’t handle the real me.”

Vishnu descending again and again when dharma declines. Christ promising to return. The Hopi waiting for the Blue Star Kachina. Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, teaching and departing with a promise to come back. Avalokiteśvara in the Lotus Sutra saying, “I take whatever form beings need.” Did you just read what I said? They’re updates from the same Source for different cultures. If these were just inventions, why do they line up like a single melody played on different instruments?

We still listen to priests, prophets, channelers. We still build wars, governments, and entire value systems around the words of people who say they’ve spoken with something beyond themselves. Even people who swear they’re atheists live inside legal and moral systems built on ancient revelations. It’s like an operating system running under the surface of humanity... same code, different interfaces. Pretending it’s not there doesn’t make it disappear.

To me the evidence points to one Source, fractaling through time, speaking through masks we can handle. Sometimes luminous, sometimes terrifying, but always shaping the next step of our story. Krishna wasn’t kidding when he told Arjuna he wouldn’t like the “real” him. We’ve been shown only what we can handle; and that, I think, is what all the masks are for.

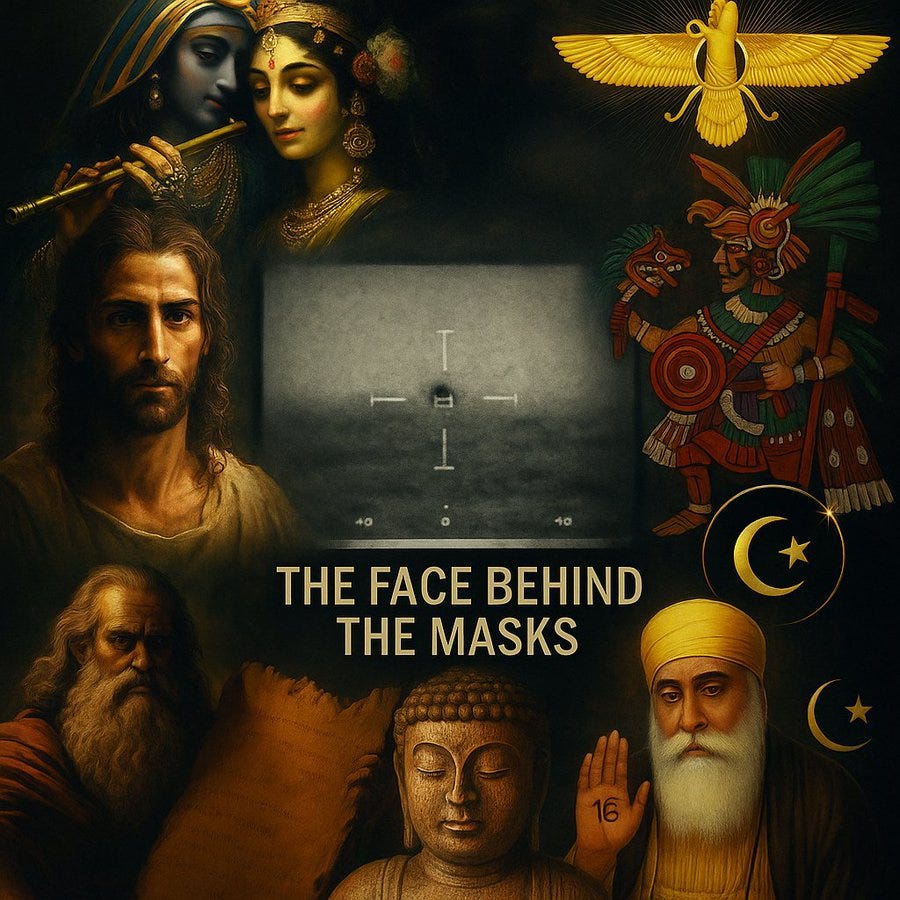

Jason included the following image with his post:

Again, I find this line of thinking very intriguing. I’m not saying it’s conclusive, or can’t be argued with, but I think its basic line of inquiry is pointed in a worthwhile direction.

In the years since leaving my very dogmatic, epistemologically-closed religion, I’ve thought a lot about WHY most people are and have always been religious while simultaneously unable to prove which, if any, religion is “the most true.”

Somewhere along the way, Catholicism (the only thing I ever was, until I wasn’t) started talking about how other religions have “part of the truth,” and pains have been taken to try to assert that all monotheists “worship the same God” — even when their beliefs about that God are clearly too different to be representative of the same deity.

I think about certain preternatural/supernatural experiences I’ve seen others go through, which make it impossible for me to be a materialist even in my doubt, but which also make me wonder whether these things are as described by any given theology, or are a different phenomenon that various religions have tried to come up with proprietary explanations for.

David Bentley Hart has a great insight in his book, That All Shall Be Saved, that I’ve come back to a lot in my mind:

If, however, we are...presented with a comprehensive story that purports to be nothing less than the total narrative and total rationale of all God’s actions in creation, then we may indeed pass judgment on that story’s plausibility.

In fact, it is morally required of us to do so; not to judge is a dereliction of our rational vocation to know and affirm the Good. And here, recall again, we are not assessing God’s acts against some higher standard of ethical action; we are merely measuring the stories we tell about him against his own supposed revealed nature as the transcendent Good. It is our story that is being judged for its internal coherence, in keeping with our rational grasp of justice and benevolence, not God who is being judged according to some external scale of ethical values.

I’m not saying that Hart would agree with the way I’m using this idea here; he might very well reject it. But if we can question, as he does in that book, the idea that eternal conscious torment could ever be a just punishment for any crime committed by finite beings with limited (and even corrupted) knowledge, intellect, and will, then I think we can extrapolate it further to a question about what God is really like and what he really wants and whether there is, as it were, one religion to rule them all and one religion to bind them.

Even as a theistically-inclined agnostic, I find myself defending certain points of Catholic doctrine in discussions with people who seem to take the idea of being Catholic as something more permissive than the Church thinks it is. People who identify as practicing, generally orthodox Catholics who nevertheless will look at certain aspects of non-negotiable (from a magisterial standpoint) belief and say, “Eh, I’m sorry, I just can’t make myself believe that.”

I get it. There are a bunch of things about Catholicism I can’t make myself believe, and I’ve thought at times that if I weren’t so compelled by its authority structure to offer religious obsequience to these things I might still be able to be Catholic. It remains my fundamental frame for understanding the world, because it was built into me starting at such a young age and I spent so much time immersed in it. It feels more “natural” to me (though it may in fact be just nurture) to believe and practice religion in a Catholic way, if I were to once again practice instead of merely offer dubious prayers to a God I’m not sure is even there, than it would to just up and change professions to something like, say, Eastern Orthodoxy. The latter has things about it that are more appealing to me, and things that are less. But to “switch teams” as it were would feel very jarring and incongruous indeed.

I don’t say that to rule it out. I only say it to observe the tension…the resistance to changing out one all-encompassing model of belief for another that is somewhat similar but also different in many essential aspects.

But isn’t this the human experience across the world? Aren’t we all shaped by where we are born and what culture we are born into and what familial practices have been in place for generations and how our particular race or culture tends to think about certain things (whether naturally or through societal conditioning), etc.?

If you’ve never done real evangelization — the kind where you try to convert some stranger to the supposed truth of your way of thinking — perhaps you’ve not encountered the innate difficulties of trying, through mere words and ideas and explanations of doctrines, to change another person’s entire way of approaching the numinous.

I happen to have done a lot of it, and there’s nothing easy about it.

But even so, the vast majority of us are reaching, in some way, towards the divine. We do not want to live in a nihilistic universe where the only meaning is that which you impart and the then it all goes up in smoke once entropy takes over and biological processes shut down. Perhaps, like me, you find that the answers offered by various religions are insufficient, but you also know that science doesn’t have any better ones.

At some point, whatever you believe (or don’t) takes some measure of faith that it is the most correct path.

You cannot know what you cannot know. You cannot prove what you cannot prove.

But the pursuit of those answers, to the best of your ability, is probably the most important single thread of activity you can do in your life. Question it. All of it. Point out the things that don’t make sense instead of lying and pretending they do. Remind yourself, if you’re a more dogmatic sort, that the things you believe are absolutely and unquestionably true about God didn’t come to you through some form of direct revelation, but through human intermediaries who very well may be misrepresenting their alleged divine inspiration or mediation, in whole or in part.

That doesn’t make whatever it is that lies beneath, the very substrate of reality, less real. It only means that its full contours cannot be known by creatures such as us, with limited reasoning powers and sensory apparatus and so on.

And that’s why, to me at least, the kind of triumphalistic certitude of the zealot has become so unappealing. You can’t learn anything with a full cup. You can’t take for granted what cannot be proven without doing a fundamental injustice to the pursuit of truth.

Epistemological humility — the willingness to admit that we “see through a glass, darkly,” and that our theology and ontology should be reflective of that, leaving openness to certain adjustments and a lot less ironclad surety — appears incredibly necessary for true meaning seekers.

A priori assumptions framed as beliefs are “a jig” as my friend Kale Zelden might call them. A jig is a tool; a filter; a limiting frame that allows a certain ease of use in the fabrication of things. But your table saw can do lots of different things, and other jigs or even free-form application are possible. If you forget this, and you start thinking there’s only one jig, one limiting filter, one type of product you can make, you’re missing a world of other possibilities.

In my Catholic days, I used to rant a good bit against religious indifferentism and syncretism, and I might still do that even now. If God is real, there’s a better than average chance that he cares what human beings believe about him. The problem is, there’s no way to check your answers. I don’t like the syncretistic impulse to mash different kinds of beliefs together and present that as something real and coherent, when it’s just a pastiche; a bespoke construct of our own making.

Where I would not so readily object to such things is in the person who uses this kind of cafeteria belief system as a heuristic that is perennially subject to revision when new information is found. The Problem of Divine Hiddenness remains a very real obstacle to faith. So if we are left to our own devices to try to ascertain why we are so inclined to believe in a God or gods despite that hiddenness, there’s going to be a certain amount of trial-and-error in assembling a collection of understandings and beliefs that strike us as the most likely to be true.

We just have to resist becoming stuck there when we have reason to revise.

To return to the central theme, it does not strike me as irrational to approach the idea of a singular phenomenon wearing different masks as worthy of consideration. That doesn’t really preclude the notion that some religions are more true than others, or that one might actually be the most true of all.

Clearly, the Christian notion is one that demands to be reckoned with in a way that others don’t, because it is a story of a God who not only inserts himself into human affairs, but who becomes one of us, to elevate our nature in such a way that we, too, can become more like him.

While I don’t find C.S. Lewis’s trilemma quite as ironclad as others do, I absolutely believe it’s something to be grappled with. It can’t merely be dismissed:

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. ... Now it seems to me obvious that He was neither a lunatic nor a fiend: and consequently, however strange or terrifying or unlikely it may seem, I have to accept the view that He was and is God.

I can imagine other conclusions than those laid out here, but I haven’t thought them through deeply enough to feel confident in presenting them yet. But there really is a kind of mutual exclusivity between notions of Jesus here, and Lewis is right to point out the superficiality of “the great moral teacher” hypothesis.

All of this is to say: I prefer, for now, not to be locked into the dogmatic presumption of correctness about one particular paradigm, even if I believe those who subscribe to a particular paradigm should probably be logically consistent in accepting its dogmas and not just picking and choosing. But I do understand, if each religion is making its own imperfect attempt at knocking on heaven’s door, so to speak, why some are inclined to say, “Well, I think this is mostly true, but this is where it strikes me as off; perhaps that aspect is just some man-made accretion.”

At the heart of all of this is something I hope we can all agree on: it matters very much to try our best to figure out which things about the supernatural realm are true, as far as can be ascertained, and to hew as closely to those truths as we can.

If you liked this essay, please consider subscribing—or send a tip (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe) to support this and future pieces like it.

"If God is real, there’s a better than average chance that he cares what human beings believe about him. The problem is, there’s no way to check your answers."

Steve, thank you for sharing this. I see a lot of myself in this post, in the questions that you are asking. I am reminded of paths that I went down after the breakdown of my first marriage, when I lost all faith for a time, trying to make sense of my broken life. I think for those with an intellectual and mystical bent, especially those who have experiences that seem hard to cohere into a consistent world view, the idea of what is effectively a form of gnostic perennialism (the idea that all manifestations of faith in the world point, at their heart, to the same hidden God, for those with eyes to see) is always going to be attractive. From a certain perspective, even within more small "o" orthodox expressions of the Christian faith (I cannot speak with any deep clarity or knowledge outside of these traditions) such a statement even has a hint of truth about it: the essence of God is hidden, is too big to comprehend, we are given our material human frame in time and space because the ontological reality of existence is too big for us to comprehend as we are now, and the truth of reality's Creator breaks out (fractally, if you will) within all aspects of the created order, even within religious traditions which (may) owe their origin and allegiance to the demonic because the glory of the truth of existence cannot stay hidden and even the demons serve the Master of all in their disobedience.

But within this heuristic, I think we see the seed of why this position is not going to help us in the end. The vision Arjuna receives of Krishna, whatever it represents (I tend to think it represents a half truth at best, but that is another matter), is not something within which he can reasonably abide. What is needful is not just Truth in an absolute ontological sense (though the human yearning for this Truth is real and good) but a subjective, individual, and personal version of this Truth that touches us and reaches us where we are, in the particularities of our own story. Back in my teens my younger self wanted, I think, to figure out a way to touch the Absolute essence of what I have come to recognize as God the Father, unmediated. I now think that's impossible, a fool's errand born of youthful pride (in fact, for me at least, what it represented was the creation of an idol of my pride, which had become my true god). As you say, Christianity is worth a special look because it posits the God who sacrificially inserts himself into the affairs of man. While perennialism tries to weave this story into some semblance of the "dying god mythos", it never seems to fit very well, being too encumbered by historic particularity and (what is worse) an appalling degradation and humility.

I say all of this just to note that, at least for myself, I struggled for a long time trying to meet God in a way that was bound to result in failure. Your quote that I provided above got me thinking in this direction. Your first sentence seems entirely correct to me, but I wonder based on the content of your second sentence, where you suggest that there is no way to check your answers, whether you may have found yourself struggling with something similar? In an abstract sense you are correct, there is no way to create a proof whereby the veracity of any given theological claim can be measured. But I don't think this has ever been the sense via which humanity, whether in the Christian tradition or any of the other traditions you referenced, have experienced the divine (or, quite frankly, how we have ever experienced ourselves). Visions are great, insofar as they go, but they may be entirely beside the point--I may have once had a relatively minor such experience, but frankly it ultimately didn't do much for me one way or the other. What has been surprisingly useful is dwelling on the particularities of my own story--the things I lost, the people I've hurt, the undeserved pain I've seen, the undeserved blessings I've received, the punishments I've been given that turned out to be blessings, and the utter powerlessness I experience when I consider my place in the fabric of creation--and meditating on this while meditating on the the experience of Christ as recorded in the Gospels. The fruits we glean when we approach this process seriously and faithfully, I think, that actually can be tested, and either found true or wanting, as we incorporate them into the particularities of our lived existence.

Again, your point is taken: Lewis's argument is (frankly) not that good as a logical argument (though it does seem to correlate reasonably well to the evidence born via the historical record as we currently understand it), and there is such a grab-bag of competing cosmological dogmas to choose from. And you could probably take the methodology proposed above, apply it to the prophetic figure of another world faith tradition, and yield something via the endeavor. But you're not a cosmic being approaching this as a rational mind separate from the system. You are an individual historical person, born in a particular place, in a particular time, to particular parents, inculcated in a particular tradition, who has made particular choices. We only experience anything as a particularity, and it is to the history of our actual existence that we owe allegiance, wherever it might lead. So the question is, what approach is most likely to allow you to wrestle with the issues that lie at the heart of your pain (at least insofar as you are able to perceive them, this is an unending well)? Whatever else it might be, I doubt the path of the universalizing myth is likely to yield much fruit.

I have rambled too long, but I would urge you to focus in on what meaning there is to be found in the particularity of your experience, and to take care when considering the apparent profundity of the perennialist myth. I wish you well in your travels, both on the road, and into the depths of your soul.

I'm a computer programmer. Not a theologian (nor a Catholic). Even still I have been considering writing a book on the "proof" of God, as the evidence seems quite overwhelming to me, and yet not many people know about it. I'm talking about the Rare Earth theory promoted by Hugh Ross of Reasons To Believe. He was trained as an astrophysicist and simply pulls straight from scientific journals the ever increasing reasons why it is highly improbable to have a planet like ours. It is especially difficult because it takes billions of years to essentially terraform our planet so we can live here, and that means our planet has to remain stable for several billion years. Each stage of life prepared the way for the next stage of life.

And all that time, you can't have things like the gas giant planets moving into the inner part of the solar system (something that normally happens). You have to have stable tectonic plates, which most planets don't have. You have to be birthed in the inner part of the galaxy to have the elements we do, but thrown out to the correct distance so your system doesn't get sterilized by cosmic rays from the central black hole. On and on it goes, hundreds of criteria that must be met to have Earth. Even if some turn out to not be the case, there are still plenty left to show we are really rare.

We're so rare that you have to bring in a multi-verse to have any chance to get Earth. And once you go there, you're essentially appealing to infinity to make the chances work out in your favor, but then everything becomes possible, which isn't what you want either.

The Rare Earth theory doesn't just show there must have been a Creator who made this possible, but it shows a Creator that is actively involved at each step in the "construction" process. Even more amazing is the implication that He has created the entire universe just to have planet Earth - which implies just to have us. The universe even has to be the size it is or you couldn't have a planet Earth.

In other words, we are living in an age when for the first time in history, man can clearly see just how abundant the evidence is that God made us and put us here for a purpose.

But it doesn't stop there. Hugh grew up a non-Christian in Canada where he knew no one who was a Christian. And yet he reasoned that a god who would create us, must have left a message for us, and so surely one of the holy books of the world should reveal this god. And so he went about studying the various holy books to see if there was anything that showed erroneous views of science. Most religions have clear scientific errors. And then he set aside an entire year to study the bible. Instead of finding errors, his secular mind found things the bible got right time after time. It so stunned him, that he calculated the probability which is astronomical and convinced himself that the bible truly had to be from the God who created the universe.

But then consider all the prophecies from the old testament that accurately predicted Jesus and what he would do. We know for a fact that these were written prior to the time of Jesus because we have the Dead Sea scrolls.

And then you have the Shroud of Turin. It confirms many of the things written about the crucifixion in the gospels and yet even more, it shows an image that science can't duplicate. The scientists who went to study in the 70's, went after they heard that the Shroud contains 3D height information in the image. This is like a scientist hearing you have an artifact from a UFO that that has a property that you know is impossible. You drop everything to study this artifact.

And then you have the symbolism from old testament scriptures that for no apparent reason perfectly demonstrates the gospel story. Think of Abraham, the father of faith, who God asked to sacrifice his son. Or consider Joseph who interpreted the dreams of both the baker and the cup bearer. Why two? He only needed one to tell pharaoh. But the two match the two thieves on the cross with Jesus. One lived, the other died on a tree with the birds eating his eyes out. Or read the story of Jonah, where it describes him sinking to the very bottom of the sea, and sounding very dead. Hmm, dead for three days in the belly of a fish only to be raised back to life causing the city of Nineveh to repent. And Jesus said the only sign the Jews would get was the sign of Jonah. It all fits.

Archeology keeps uncovering more evidence that backs up things written in the bible. But just look at the story of Lot in Sodom. More recent digs at a tel in the Jordan river delta show it was destroyed by an air-burst meteorite that hit around the time that fits the bible. Read the story again and you'll see the angels telling Lot he has to hurry and then dragging him to get moving. They knew a meteorite was headed their way and time was of the essence. And then look at Lot's wife who looked back on the city just as it was hit. That 2000 degree shock wave sent out molten salt and sand that could well have instantly encrusted over her body if she was at the right distance.

Or just pick up a leaf and ask yourself how did it get here? What did it take for that leaf to exist at this time on this planet? Most people have no clue what was needed to happen to get that leaf. Nor do they know how absolutely impossible it is to get the first cell through random chemical reactions. Watch some of Dr. James Tour's videos on YouTube for details on the impossibility of abiogenesis.

Or just look at our perfect moon. It's size alone saved Earth from becoming tidally locked to the sun which would have destroyed all life. And only over the last few million years has it been in the correct position to give us perfect solar eclipses. This is so rare in itself that there are likely few other planet moon systems that have perfect solar eclipses anywhere else in the entire universe. Talk about a sign in the heavens!

Our planet is perfect. Our moon is perfect. Our sun is perfect. Our solar system is perfect. Our galaxy is perfect. Our local galactic group is perfect. Everything is just right and shows beyond any doubt that we were put here on purpose, by a God who has spoken to us through scriptures, and who came in person to teach us and die for us.

And now we can see it. Which means we're here at the climatic last part of the entire story God has been writing. It used to take faith to believe in Him. Now, given the evidence, it simply takes the will.