No Time to Be Human

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

If you find value in my writing, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Prefer one-time support? You can leave a tip (click “Support TSF” below). I have removed the PayPal and Buy Me a Coffee links in favor of one that goes directly through Stripe, which processes my subscription payments. There are issues with those other platforms that make Stripe the preferential option.

Thank you for reading. You keep this work going. And I want nothing more than to write as often as possible.

The road that enters the subdivision where my family currently lives is a beautifully landscaped and winding road under the dappled light that filters through a canopy of lush, green trees. The median is decorated by mature hedges, perfectly shaped and kept perfectly trim, punctuated by what I refer to as “Sesame Street Lights.”

If you grew up watching the show, you know exactly what I mean:

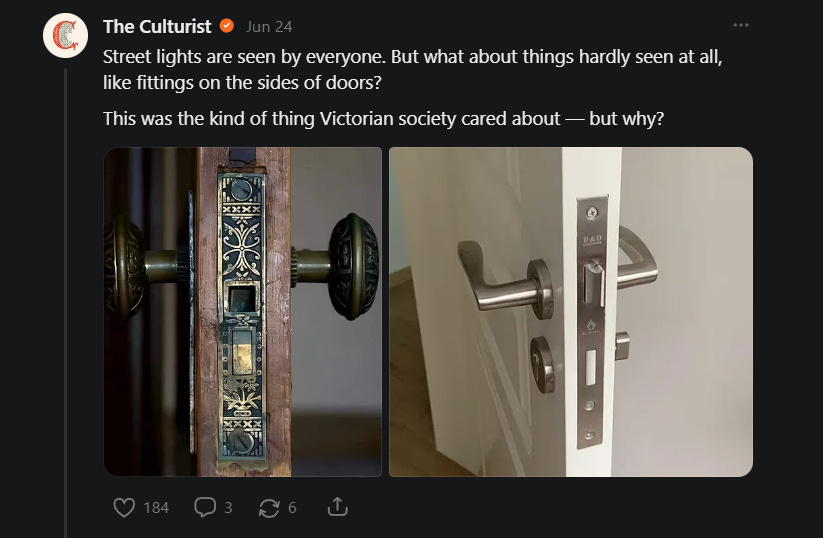

I was reminded of this imagery this week when I came across the following thread in my Substack feed, from The Culturist:

There are other great pictures in the thread. Like this incredible strike plate for a simple doorknob:

I would posit to you, gentle reader, that the reason we no longer make things like this is because we have completely lost our ability to experience and make proper use of time.

Those of us who are older remember the last remnants of the world that was. The one before everything was cheap and disposable and we had our faces glued to screens all day.

We remember cold, rainy springs, the bright yellow of daffodils illuminating a gray-brown landscape of dormant and dead things, the trees at last budding their fresh green leaves, that turned darker as the sun returned with its warmth.

We remember a seemingly endless summer spent outside. Climbing trees, riding bikes, playing hide and seek or capture the flag, building forts, making guns out of sticks, wandering the streets and back alleys of our neighborhoods, hanging out with friends, eating popsicles on the front steps, and drinking from the hose.

We remember autumns of leaf piles and pumpkins, trick-or-treating well after dark, and Thanksgiving tables loaded with homemade foods, with the company of family and friends.

We remember winters with deep piles of snow, and sledding, hot chocolate and hearty stews and maple sap boiled on the red hot surfaces of wood stoves.

These have become content cliches for the nostalgia farmers of the internet, but they were real experiences, nearly universally shared, in all their unique and regional variations.

I’ve related my origin story almost as many times as the never-ending series of Batman movies, but I’ll do so again: I was born in Upstate New York, but spent the most formative years of my childhood, from about age 5 to age 11, in a little town called Stafford Springs, Connecticut. I lived on Fiske Avenue in a home built in the early years of the 20th century, and I would also walk the half mile or so to the old red brick public library, where I’d spent countless hours going through the books.

We watched some television in those days, but not a lot. The Cosby Show. The Dukes of Hazzard. Saturday morning cartoons. The evening news and Sunday football with Dad.

We got our first personal computer when I was 10 years old — an IBM clone running on an 8086 processor with two 5.25” floppies, no hard drives, a 4-color CGA video chip, and a whopping 640K of RAM. I wouldn’t experience the internet for the first time until five years later, and when I did, it was so basic it hardly warranted hours of aimless scrolling.

Nobody had a cell phone, because they weren’t invented yet. Nobody had to check their email at night to see if there were any urgent messages from work.

My father worked for a company I don’t really remember anything about. In the evenings, he would go up to the little room with the bright yellow walls in our creepy attic that he used as an office. There, he would make sales calls for a couple of hours on a landline phone, usually until I was already in bed.

It was the first time I was aware of that anyone ever had to work when they weren’t at work.

There was a definitive distinction for most people between home life and whatever they did outside the home. They came home from work or school, ate dinner, had their recreational pursuits, maybe watched some television. If they were lucky, they had cable TV, which offered far better reception and more channel options than the old rabbit ears antennas we had to constantly fiddle with and adjust.

Time passed so much more slowly then. I don’t remember the feeling, now so common, of always being rushed. Not just because I was a child. I don’t remember my parents acting as though they felt that way either. Even when my dad worked late in the attic, it was after dinner, and at a reasonable pace.

There was time to simply live.

Over the next decade, that would all begin to rapidly change.

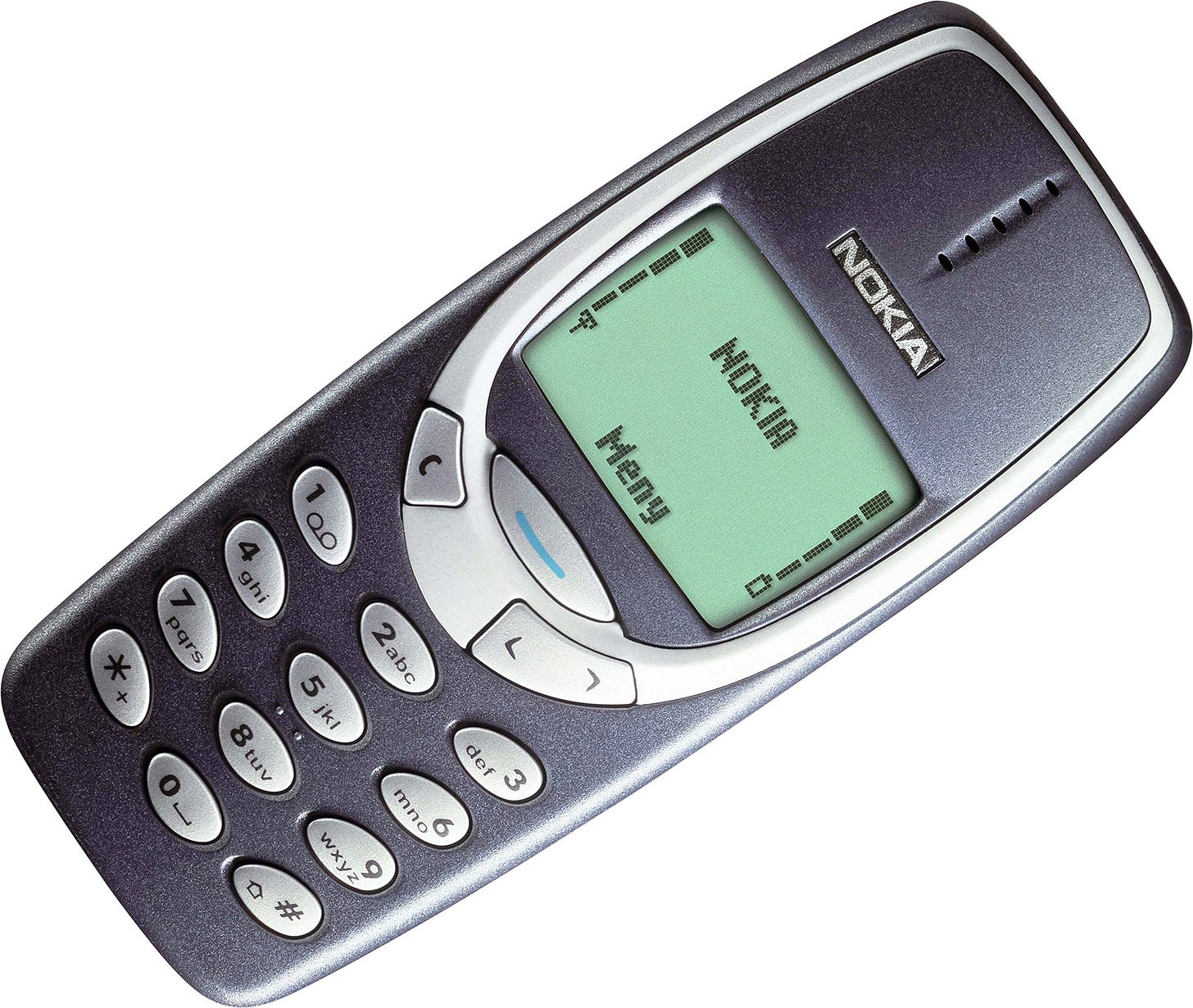

I was about 25 when I got my first cell phone. It was a little Nokia 3310, a blue brick of plastic with a green backlit screen and an LCD display. It looked like this:

The only game I remember being able to play on the phone was the “snake” game, where you had to maneuver the poorly-animated snake around the screen as it grew larger, trying to go for as long as you could without the thing running into its own tail.

The internet existed by then, but it was not something you could access on your phone.

I remember talking to Paul, one of my best and oldest friends, around the time cell phones were becoming ubiquitous. He insisted that they would be the downfall of civilization. I laughed, like I often do at the luddites in my life, asking him why he thought such an incredible invention would cause such problems.

I don’t remember what he said. So, with no small irony, I texted him earlier this week to ask him how he’d known, and what it was that he saw.

“In my opinion,” he replied, “society is built on relationships, and relationships are built on the ability to communicate properly with one another.

I think modern forms of communication have greatly deteriorated our ability to communicate with one another, and therefore are detrimental to our society and culture.”

He isn’t wrong.

I remember being in 6th grade, just beginning to really take an interest in girls, and spending hours on the phone every night, stretching the long, curly cord of our beige, landline receiver down onto the basement steps, or into the family room — wherever I could reach so I could close the door and talk without being bothered.

I can’t say I’ve ever seen one of my children have a phone conversation with their friends. They text. They message. The one exception would be the way my two adult teens sometimes play video games with their friends on the other side of the country, talking to each other over Discord or using in-game voice chat as they play. But they don’t just call to have a conversation. They talk about whatever shared in-game mission they’re on, or which boss they’re going to fight together, or which items they need to upgrade their weapons or armor.

A few months ago, my phone camera began breaking, and it just kept getting worse as time went on. I couldn’t access all the different focal lengths, and sometimes I’d get a blank screen with no image at all. But I need it for gig work, and its growing dysfunction made my life hell a week or two ago. I couldn’t perform the barcode scans or take the receipt photos I needed to complete my deliveries.

So I dropped $200 at the Apple store — money I didn’t have to spend — to get it fixed. I need the phone to make what money I can, and even though the phone is four years old and eligible, I can’t afford the $1100+ it would cost to get an upgrade.

I left it at the Apple store at 2:45PM. I couldn’t pick it up until 6PM the same night. It felt so weird to go home without it.

Like a phantom limb.

I had to figure out how to drive back using my van's ancient built-in navigation system, which hadn’t been updated in years. I couldn't text my wife from the grocery store to make sure I got everything she needed for the dinner we were making. I couldn't ask ChatGPT to look up anything I was thinking about on the road. I couldn't select music, or a book to listen to. I had to double check to make sure I had a physical wallet so I could buy the groceries we needed without just tapping my phone and using Apple Pay.

It made me realize that these damn things have an electrode in every aspect of our lives.

Try going somewhere without it. Just for a few hours. You’ll see what I mean. You have no idea how much you reach for it until it isn’t there.

We don’t allow ourselves to be bored anymore. We don’t have downtime. It’s not just doomscrolling, either. We feel an obligation to read the articles we’ve saved for later, watch the videos our friends and families send us, respond to the texts and emails we’ve been neglecting, and settle our feelings of FOMO by checking to see if any crazy news event has happened since the last time we looked.

We can no longer focus long enough to read whole books. Entire services are springing up out of the AI industry, offering to summarize texts so we can learn the basic concepts without actually reading them. Even audiobooks listened to while running errands or going for a walk feel like a chore if they’re not played at some multiplier of their native speed. Who has 9 or 10 hours to spend on a book? Can’t the author just get to the point?

Everything is being compressed so we can fit more in to every day. We wake up and go to sleep looking through little rectangles of glass to see what’s happening everywhere but right in front of us.

I had already begun writing this essay when I came across a Substack post entitled, “compression culture is making you stupid and uninteresting”:

It's the logical endpoint of an attention economy that treats human focus as a finite resource to be optimized and monetized. If attention is scarce, then efficiency becomes the highest value. If time is money, then anything that takes time without producing measurable output becomes waste.

Social media platforms discovered they could capture more attention by providing rapid-fire bursts of information rather than sustained engagement with complex ideas. Facebook’s algorithm doesn't reward posts that make you think deeply… it rewards posts that make you react quickly.

And of course, we've built an entire economy around compression! Bloggers get clicks for "5 Key Takeaways" while deep exploration of messy complexity gets ignored. Podcasters are celebrated for "actionable insights" while wandering conversations that might actually lead somewhere unexpected are dismissed as waste. Authors are strong-armed into chapter summaries and bullet points because we've trained readers to demand the intellectual equivalent of fast food.

The result is a race to the bottom of human attention, where the most successful content is the most easily digestible, the most quickly consumed, the most immediately useful.

We've built a culture that worships efficiency over depth, optimization over exploration, answers over the sacred act of questioning.

And it’s killing our ability to create.

We can no longer imagine, because our minds are being stuffed full of external imagery and information, which suppresses our ability to conceptualize and visualize new ideas.

Our films and shows are almost all remakes. Popular books are often ideological (especially if they’re fiction) or variations on a theme. Most podcasts seem to recycle the same basic roster of guests — which is fine if they have something of interest to say, but at some point, we need new voices.

We do TikTok challenges instead of real creation. We learn how to imitate others who are successful at the things we want to do until everyone is doing the same thing and it doesn’t work anymore. When a viral theme emerges, everyone jumps on the bandwagon until it’s so played out, nobody cares anymore.

Our culture has become more mimetic than even René Girard ever likely anticipated.

In his book Happiness and Contemplation, the late Josef Pieper — the author of another relevant book you may have heard of — Leisure: the Basis of Culture — wrote that

Seeing, in itself, makes for happiness — and this, too, say the ancients, is a connection between contemplation and happiness. “We prefer seeing to all else” — these words are to be found in the first chapter of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. If we did not already know that joy in seeing must be counted among the most elemental, irrepressible, coveted joys of mankind, we could deduce it from the everyday phenomenon of “concupiscence of the eyes,” the hypertrophy of visual curiosity, the morbidity of the contemporary craving to see. We can deduce it from the extent of this degeneration which, it seems, is imperilling specifically our most elemental and precious powers….177 This, incidentally, may suggest that the greatest menace to our capacity for contemplation is the incessant fabrication of tawdry empty stimuli which kill the receptivity of the soul.... [emphasis added]

What does Pieper mean by receptivity? Earlier in the book, he offers this explanation:

The Latin words contemplatio, contemplari, correspond to the Greek words theoria, theorem.124 Cicero, Seneca, and undoubtedly many other less famous writers established the Latin words as coordinate with the earlier coined Greek words in the course of those comprehensive labors of translation which characterized the early history of the Latin West.

Theoria has to do with the purely receptive approach to reality, one altogether independent of all practical aims in active life. We may call this approach “disinterested,” in that it is altogether divorced from utilitarian ends. In all other respects, however, theoria emphatically involves interest, participation, attention, purposiveness. Theoria and contemplatio devote their full energy to revealing, clarifying, and making manifest the reality which has been sighted; they aim at truth and nothing else. This is the first element of the concept of contemplation: silent perception of reality. [emphasis added]

But how can we participate in the silent perception of reality if our minds are full of noise?

Writing at his Substack, White Noise, Tom White describes our problem with “The Great Distraction”:

Screens have become our first glance in the morning and our last look at night. We cradle our phones like talismans and rely upon them like pacifiers, whispering with every tap: please distract me, please numb me.

By doing so, we’re not only spending time, but also squandering ourselves.

The average human on planet Earth now spends an average of 6 hours and 38 minutes per day staring at a slab of glass, and teens log even more.

White links to a 2024 Pew Research study which says that “Nearly 1 in 5 teens say they’re on YouTube, TikTok ‘almost constantly’.”

He continues:

The dopamine spikes from TikTok or Instagram Reels give us the illusion of being entertained, but the cost is a fractured mind that can’t hold a thought long enough to create something meaningful. We are mentally overdrawn.

This wasn’t always the case. Per Patrick Collison, we used to “quickly [accomplish] ambitious things together.”

His personal site lists out a number of incredible examples:

P-80 Shooting Star. Kelly Johnson and his team designed and delivered the P-80 Shooting Star, the first jet fighter used by the USAF, in 143 days. Source: Skunk Works.

JavaScript. Brendan Eich implemented the first prototype for JavaScript in 10 days, in May 1995. It shipped in beta in September of that year. Source: Brendan Eich's history of the language.

The Empire State Building. Construction was started and finished in 410 days. Source: Empire State Building.

Back when attention was cheap, we shipped miracles. We used to build big things and complete inspiring projects quickly, efficiently, and impressively. These feats were not magic. They were the product of sustained, undiluted attention, the output of a culture that prized focus, urgency, and daring.

White says that he believes “every technological breakthrough is first embraced, then abused.” Or, put another way: “Give a human a tool, and we’ll use it until it blunts the part of us it once sharpened.”

He then offers an insight I’ve written about before (but admittedly, I rarely stick to my own advice):

Boredom is a crucible. It’s where Newton saw the apple fall and where Edison brooded over light. Take it away, and you take away the soil where deep thought grows.

I can write all of these things because I know they’re correct. I know that I need to:

Spend more time offline

Not reach for my phone at every red light and grocery store line

Stop scrolling and go to sleep on time

Not look at my phone first thing to “wake up my brain”

Not let FOMO dictate my online behavior

Read real books without giving into the need to post something about them every five minutes

Stop chasing cheap dopamine and do real work

The list is certainly longer than this. But even as I write these things, some part of my brain is saying, “Yeah, but you’re not really going to do all that, right? Not yet, anyway. The way you do things now is way too enjoyable to change, even if the cost is never feeling satisfied with anything you do.”

We are caught in a recursive loop, and we need to find our way out, before something forces us to remember what it means to be human.

It reminds me of one of the most famous Twilight Zone episodes, “Time Enough at Last.” Here’s the plot synopsis from Wikipedia:

Bank teller and avid bookworm Henry Bemis reads David Copperfield while serving a customer. He is so engrossed in the novel that he attempts to regale the increasingly annoyed woman with information about the characters, and shortchanges her. Bemis' angry boss, and later his nagging wife, both complain to him that he wastes far too much time reading "doggerel". As a cruel joke, his wife asks him to read poetry to her from one of his books; he eagerly obliges, only to find that she has crossed out the text on every page. Seconds later, she destroys the book by ripping the pages from it.

The next day, as usual, Henry takes his lunch break in the bank's vault, where his reading cannot be disturbed. Moments after he sees a newspaper headline, which reads "H-Bomb Capable of Total Destruction", an enormous explosion outside shakes the vault, knocking Bemis unconscious. After regaining consciousness and recovering his thick glasses, Bemis emerges from the vault to find the bank demolished and everyone in it dead. Leaving the bank, he sees that the entire city has been destroyed, and realizes that, while a nuclear war has devastated Earth, him being in the vault has saved him.

Seconds, minutes, hours—they crawl by on hands and knees for Mr. Henry Bemis, who looks for a spark in the ashes of a dead world. A telephone connected to nothingness. A neighborhood bar, a movie, a baseball diamond, a hardware store, the mailbox at what was once his house is now a rubble. They lie at his feet as battered monuments to what was but is no more. Mr. Henry Bemis, on an eight-hour tour of a graveyard.

Finding himself alone in the broken world with canned food to last him a lifetime and no means of leaving to look for other survivors, Bemis succumbs to despair. As he prepares to kill himself using a revolver he has found, Bemis sees the ruins of a public library in the distance. Investigating, he finds that the books are still intact; all the books he could ever hope for are his for the reading, and all the time he could ever hope for, to read them without interruption.

His despair gone, Bemis contentedly sorts the books he looks forward to reading for years to come, with no obligations to get in the way. Just as he bends down to pick up a book, he stumbles, and his glasses fall off and shatter. In shock, he picks up the broken remains of his glasses and breaks down in tears, surrounded by books he now can never read.

I remember the sinking, awful feeling I had the first time I watched that episode. As a child, I was a voracious reader, and preferred it over many activities.

But today, we’ve sentenced ourselves to Bemis’s fate. Books have never been more accessible, and yet, few, if any, of us bother to read them. We are being absorbed into the algorithm. We are becoming slaves to the machine.

We have left ourselves with no time to be human.

If this resonated, consider subscribing—or send a tip to support future pieces like this.

Maybe the worst part of the late Gen X experience is realizing how much we’ve given up on our lifetime, and how little we got to enjoy the old world.

An excellent piece, Steve.

Just yesterday, in a conversation with a friend, I bemoaned the fact that lost forever are the collective moments of our childhood....

...the empty oatmeal box Mom handed the youngest to play with.

...the excitement of going to the mail box to see if the long awaited letter from a pen pal came.

...the anticipation of piling in the car, unfettered by restraints, with Dad's arm to protect us if he slammed on the breaks.

...the hours spent making roads for our Tonka trucks , which actually were built to last for years.

We've become a throw away society and the first to go are the people we use to love and care about in favor of technology. Our phone, our computer and our social media presence will not be there when we lay dying.