Social Media is Ruining Everything

Online content sharing & interactions have become critical to our daily existence. But they're also making that existence worse.

The title of this post is ripped straight from the unwritten manuscript of a book idea I’ve had in my mind for many years. I knew the theme was important, and at least a decade ago, using an online social content clipping platform that no longer even exists (the irony doesn’t escape me) I began saving media vignettes that supported the general hypothesis. I no longer remember how to access my data from that time, so those stories are, for now, lost to me.

But there’s no lack of evidence. Just look around. There’s a pretty big example unfolding right now.

As a social media addict myself, and a professional content producer, I’m well aware of the pitfalls of our new mode of information sharing, but also of the unique opportunities and value it creates. As I said to my friend Kale Zelden last week on a phone call about his own long-overdue foray into the world of Substack (you can see his new publication, The Underneath, right here), “There has never been a better time in history to be a writer than right now.” You could sub in any creative endeavor for “writer” and the proposition holds true. We have tools at our disposal that our forebears could not even dream of. We’ve eliminated most of the gatekeepers, created grassroots mechanisms for self-publication and promotion, and made the tools of the trade more inexpensive than ever before.

But we also have all this damned noise. And the quality signals are getting lost in it.

Allow me to back up for a moment, though, to offer some context.

A Brief (Personal) History of the Tech Revolution

Born in 1977, I’m on the tail end of Generation X, and I consider my demographic, collectively, as the last to truly remember the “Before Time.” Before what? The Internet, of course. The technology that changed the human race forever, rewiring our brains and the way we think, see, and interact with the world.

Ours was a childhood of analog experiences. There was no such thing as streaming or binging shows. You showed up when they were scheduled to be on network teevee once a week or you programmed (with a brief prayer that it would work) your VCR to autonomously record them and hope you wouldn’t miss the beginning or the end because of a timing issue. Early video games like those available on Atari could be fun, but looked like garbage and sucked too much to play for excessive periods of time. Music was on vinyl, cassette, or much later, CDs, but curated playlists were the realm of mix-tapes, often cribbed from careful listening to local radio and punching the play and record buttons together at just the right moment, like a finishing combo. It wasn’t until I was in college, learning how to edit video on a linear SVHS tape deck — not Adobe Premiere or Final Cut Pro — that Napster showed up to disrupt the music scene with pirated MP3s. A lot of T1 bandwidth was used up by Communication Arts majors working the lab in the late 90s, downloading whatever songs they could grab to burn onto a CD. Even then, the process was highly manual.

As kids, almost nobody was talking about “screen addiction.” Our Cathode Ray televisions looked like garbage as often as not; big, boxy affairs in archaic wood cabinets or glossy black vinyl. I still remember the day we got cable television when I was in the 2nd grade. I watched a Danger Mouse marathon on Nickelodeon, soaking it in, commercials and all, until my mom decided we’d had enough. We spent our summers playing in the dirt, grass, and trees. We played wiffle ball and frisbee and badminton and jarts. rode bikes and skinned our knees. On one particular bike race with my friend John, who was a few years older than me, he gave me a shove that sent me sprawling into some large landscaping rocks, where I hit my head hard enough to make it bleed. Nobody — not me, not my parents — even gave a thought to the idea that I needed to be bubble wrapped inside a helmet. You got knocked off that particular horse, the only solution for it was to get right back on. Also, my Frankenstein’s monster of a bike that my mom picked up dirt cheap from a yard sale had a gear shift lever from a car on the top tube. Don’t ask me why. I didn’t make the rules. Ours was a world where Saturday mornings meant watching cartoons in our underpants as mom and dad slept in, eating boring grownup cereal like cornflakes laced so much table sugar the milk sweet enough to make you gag. We built blanket forts and had action figure wars and I made “radio shows” on dollar store cassettes using a beat up old boom box given to me by our creepy downstairs neighbor. It was also the tail end of the cold war, and I watched the NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw every evening with my dad, fully aware that that we were under constant nuclear threat from the Russians, even if I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant in anything but the broadest of outlines.

My dad was in retail management when I was little, and he got transferred to new locations as often as twice a year. Born in Upstate New York, I lived all over parts of New York and Pennsylvania until around 1983, when we moved to Stafford Springs, Connecticut, where we’d stay for the next 8 years as he branched off into sales management for contractor suppliers like (the now-defunct) Grossman’s. Stafford was a small town, and I walked or biked pretty much everywhere. To school, to church, to the grocery store, to my friends’ houses, to the library, to the local Cumberland Farms convenience store, wherever. I checked in via payphones if I was out for too long. I’d swing by the appliance store downtown almost every day looking for refrigerator or washer or dryer boxes I could drag up the hill to make into a box fort. My brother Matt and I spent one whole week of summer with garden shears, tunneling through the Forsythia bushes in the back yard, up against the property line fence, so we could hide out there and spy on the neighbors. We built dangerous snare traps in the mature lilac bushes in the side yard, giant rock counterweights hanging from flimsy branches, suspended by frayed old clothesline. I knocked my front tooth out jumping out of a maple tree into a pile of leaves, having misjudged their buoyancy and landed hard, face first, on the ground. In the winter we’d sled down that same side yard hill and jump off our ubiquitous New England rock retaining wall right into the street. We staged wrestling matches on the mattress in the upstairs of the old barn out back — one that was almost certainly being used for less appropriate purposes I’d never thought to consider by the teenage girl who lived downstairs. Her boyfriend drove a pale blue K-car and had an 80s mullet and mustache. He wore pleated, acid-washed jeans, and was a bully to the Chinese kid up the street just because he was foreign, back at a time when such behavior was one of the requirements of being a cool kid. We called everything we didn’t like “retarded” and “gay” and nobody yelled at us for being insufficiently woke. We’d beg our parents to take us to Child World or Toys R’ Us or Kay-Bee so we could gawk at Transformers and G.I. Joes and He-Man and Voltron figures we couldn’t afford. To make money, I sold lemonade from the front curb like a pint-sized drug dealer, or hauled stray cans and bottles to the grocery store in trash bags to cash in on the 5 cent deposits.

We got our first computer when I was 10 years old, and when my parents told me it was happening, I was so overwhelmed that I cried. I’d been using them in school, andmy two best friends had an original Macintosh and a Commodore 64, respectively. I knew that computers were my jam, even at that age. When the thing my parents had ordered from the appropriately generically-named company, “Leading Edge Computers,” finally arrived, it was both exciting and anticlimactic. It was a boxy, beige, 8086 XT with CGA graphics, two 540K floppy drives, and 640K of RAM. The thing only worked on a native MS-DOS environment — booted from a physical disk —and could only run shareware games that got passed around in hardcopy with any competency. I bought a couple games from a software store with my sock-drawer savings, but they didn’t look anything like they did on the box. The cyan/magenta/white graphics were hideous beyond belief, and I was so disappointed.

Fast forward to 1993 and my family had moved back to Upstate NY a few years previously. My parents bought their first home in the little go-nowhere former farm town of Kirkwood, which still has a population of fewer than 6,000 people. It was a suburb of Binghamton, which is itself no metropolis, though it felt like one at the time. I worked at a local hardware store at the lavish rate of $4.25/hour, but I put in enough hours to buy my first “modern” computer - a 486 from Packard Bell, with a whopping 4MB of RAM, a 128MB hard drive, VGA graphics, and Windows 3.1. Shortly after I got it, I also installed a modem, tying up our single phone line every night until my parents wanted to kill me, but also opening up the world of local Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) and signing up for the free trials of Compuserve and America Online on the shrink-wrapped disks that spammed our physical mailboxes in those days. The AOL handshake was distinctive. If you remember, this’ll bring you back:

When the Internet Service Provider Spectra Net came into Broome county in 1993, my uncle, a more senior computer nerd, told me about it, and we became two of the first 200 users in our county. (I even got a certificate that I should have kept. It’s a piece of history at this point.) 1993 was the year I learned to socialize online, long before the term “social media” became a thing. I started pulling away from the people I happened to be thrown together with in public school, none of whom were my real friends anyway. On BBSes, IRC, and the Internet, the only thing that mattered was how smart and articulate I was — something I took heavy social penalties for in school. I quickly learned the art of online debate, and how to research topics quickly so I could have the rhetorical advantage. Search engines were a joke in those days, as were most websites, and Google wouldn’t be a thing until nearly a decade later. But the allure of it all was undeniable, and my desk was littered with reference books, filled with makeshift paper markers so I could find the information I accessed most frequently. I learned how to argue about religion and politics in those days, as I tuned in more and more to talk radio as I looked up ways to take on the casual insults the atheist techie crowd tended to lob at religious folk in forums and chats. In so doing, I learned a lot about the faith I’d been born into, in service of attempting to win arguments online, usually with people older and more well-read.

It was a liminal time, and you could almost feel the old world fading away. But how could you care, when the new one was exciting, and fast, and transported you out of your small town to anywhere you wanted to be, and the graphics were getting better and the processors were getting faster all the time?

Enter The Age of Social Media

I graduated from college in 2001, with a double major in Communications and Theology. My senior thesis was entitled, “Media, Society, and the New E-vangelization.” In it, I argued:

A tremendous obstacle in the way of this movement in the development of Catholic media is the very fear of new media forms and techniques. Rather than making false demons out of the tools that secularists use, we must learn to master these tools ourselves so that they may be used for the good. There is much to be learned from those in control of the media now in terms of style and technique. Though proper discernment must be brought to bear in order that methods that are intrinsically perverse not be unwittingly adopted, there is still a tremendous deal of authentic creativity in the hands of the media elite. Many talented people with God-given gifts are fighting for the wrong side. But what they are producing technically is nothing short of amazing. Catholic communicators must develop this same mastery of the media.

But the thing was, I had no idea how any of this was supposed to happen.

In 2001, blogs were just becoming a thing — but I’d never heard of them. It wasn’t until 2003, when I discovered the idea, decided on a platform, and started writing. I was newly married, in and out of work, and had no idea how to be successful. Desperate for some kind of engagement, I spent a lot of time leaving comments on the blogs of others, hoping they’d follow the link in my profile back to my site. The intervening years were hit or miss, but I kept at it, kept honing my craft, and kept looking for jobs that would keep me close to the action.

In 2006, I found one. I was 28 years old, and I landed a position working at an elite Public Relations firm just across the Potomac from Washington, DC. I was hired as a “project assistant,” whatever the hell that was supposed to mean, but my day to day job was media analysis. Every morning, I’d scan the news, pulling important quotes from various media stories that were either supportive or damaging to the 200-billion-dollars-annually-by-revenue automotive manufacturing client my team was assigned to. It was a major corporation with a massive, and well-earned, reputation crisis. I gave briefings on my findings at each daily staff meeting to our gathered army of former news anchors and press secretaries and bureau chiefs and political strategists and lawyers so they could decide how to respond. And then some smart people in my office figured out I was really good at writing and knew my way around blogs, and next thing you know, I’m ghostblogging for senior global vice presidents and executive vice presidents and having them stick their name on it so they could be seen as a part of this “new media” phenomenon — it wouldn’t be called “social media” until later. But I was also asked to be part of a “new media” team that looked at how corporations could interface with the new platforms that were coming out, do outreach to influencers, and use the interactive components of internet culture to help repair a damaged brand. (We even worked on a project that led to a user-generated Superbowl commercial, if you can believe that.) Around the same time, one of our college interns, Leo, told me about this thing called “Facebook” that had until recently only been available to students with .edu addresses, but was really cool.

And in the beginning, it actually was. Facebook opened its platform to the general public — outside of the academic world — in September of 2006. And almost instantly, we had an entire office full of people experimenting with it, playing Mafia Wars (remember when Facebook games were a big feature?) and trying to understand what it meant for the way consumption of information and human interaction was changing.

In a 2008 blog post for our firm’s website, I wrote:

The verdict is in: social media is not only here to stay, it’s empowering a new generation of voices that spans the divide of class, race, and economic status. This empowerment doesn’t simply take the shape of self-publication. Rather, it’s the sort of power that media, the corporate world, and governments alike can now ignore only at their own peril.

One of the most recent examples of this power is the information revolution happening in Cuba right now. The New York Times reported last month that the increasing availability of camera phones, flash drives, and illegal internet connections is making it possible for Cubans to not only receive information unfiltered by the government, but to broadcast their personal stories to the outside world. The Times linked to a video that surfaced on YouTube last month depicting computer science university students questioning National Assembly president Ricardo Alarcón on the restrictions Cuba has placed on travel, information services, wages and more. The Times reported that that the video spread quickly through Havana, seriously damaging Mr. Alarcón’s reputation.

Incidents like this are only likely to embolden Cubans to do more. Cuba is experiencing some of the defining characteristics of the social media phenomenon – grassroots, underground, and defying convention. Other recent examples include the massive demonstrations in Columbia organized through Facebook, and the outreach Queen Rania of Jordan is doing on Arab issues via guerilla-style YouTube videos.

While the breadth and scope of the social media revolution have reached unprecedented levels, at its core it’s not entirely new. The Bosnian war is considered by some to have been the first conflict to have on-site information broadcast by amateur journalists via the internet. China is infamous for its long-standing attempts to monitor and control its citizens’ internet usage, with varying results – and the current situation in Tibet underscores this. (The Olympics is also presenting China with an internet censorship problem.)

The war in Iraq – the initial “shock and awe campaign” which I watched live on my PC through a streaming feed – continues to play out from a first-hand perspective, unfiltered, on sites like LiveLeak.com. The video comes from the soldiers themselves, many of whom carry small, handheld camcorders into battle every day. The U.S. government is being forced to develop new policies on information containment as videos of operations, patrols, and roadside IED explosions play on computer screens across the globe in nearly real time.

The inescapable conclusion is simple: information has become impossible to control, even by powerful national governments. If they can’t do it, our clients certainly won’t be able to. Instead, they must learn to adapt and respond.

A week later, I wrote a post I still think back with amusement about. It was entitled, “Finally, Someone Found A Good Use For Twitter,” which detailed a young American journalism student’s escape from unjust imprisonment by an oppressive Egyptian government during the so-called “Arab Spring.” His “crime” was simply covering events on the ground. As he saw the police coming for him, he had just enough time to tweet one word from his phone: “ARRESTED”. The people who followed him came to the rescue. Within 24 hours, he had an attorney to walk him out of the jail, with the U.S. Embassy backing the effort.

I was impressed. This was a kind of asymmetrical power play I hadn’t seen coming.

I wrote at the time, “In five years of working with social media, I’ve never found something I have less use for than Twitter. I don’t have an account, I’ve never seen it in action, and I’m not sure I’ve ever even been to the website … And yet, I am compelled to admit the sheer genius of using a service like Twitter in a situation like this, where time was short and wide distribution of a short message was vitally important.”

14 years and many thousands of followers and tweets later, I have a hard time going 24 hours without using the damn website. I get most of my information there. It’s funny how things change.

Those early days were a heady and exciting time. A time before disclaimers on news articles and politically-motivated account banning and other forms of heavy handed, one-sided censorship. A time before tech mogul Elon Musk felt the need to cough up an offer of $43 billion to buy Twitter so he could free it from its self-imposed mania, and it could once again be used as a platform for the promotion of free public discourse, rather than a controlled propaganda arm of the ideological Left.

Ironically, as I was writing this piece, I discovered I had unwittingly fallen afoul of the Twitter thought police. As I logged in just now to look for something related to this piece, I saw a message saying my “account features were limited.” Why? Because I responded to a video of a man being forcibly separated by the COVID police from his grieving mother during his father’s funeral with a threat of hypothetical violence. Here’s the tweet I responded to:

And here is my offending Tweet, which I am forced to delete to re-gain access to my account:

My tweet is quite obviously not harassing anyone, or inciting anyone else to do so. It was just an authentic expression of an emotion I felt while watching cruelty play out on my screen: “You don’t touch a son trying to console his grieving mother because he’s not social distancing enough for you.”

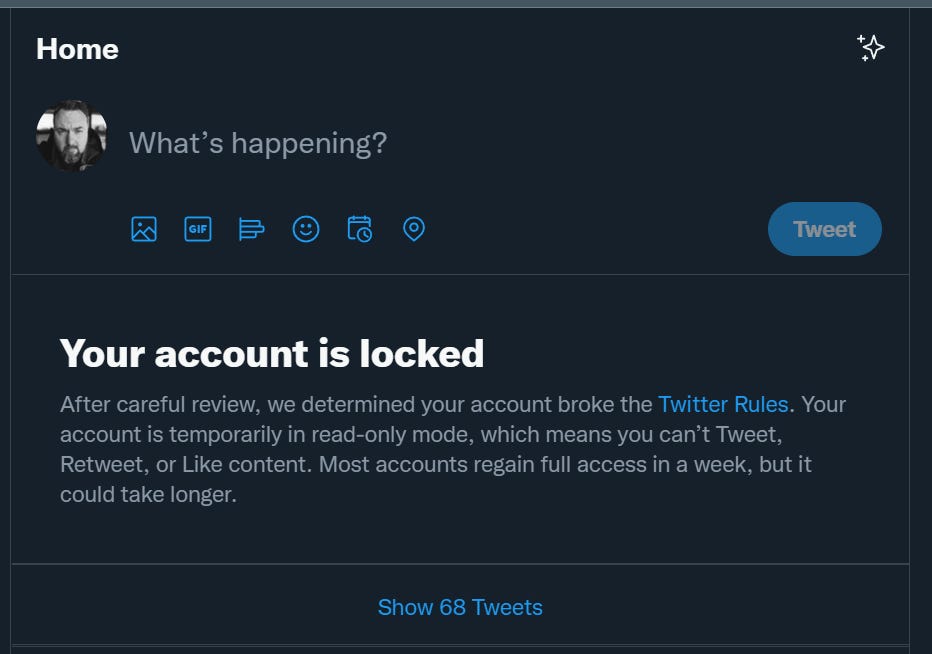

So I deleted my offending tweet — WHICH IS AN ACKNOWLEDGEMENT THAT IT VIOLATED THE TWITTER RULES, WHICH IT DID NOT — because the appeals process takes days (this isn’t my first rodeo) and often makes no more sense than the original punitive action. And even after I comply with their demand that I say 2+2=5 just so I can get on with my life, I receive this. It’s infantilizing:

And this, at the top of my feed:

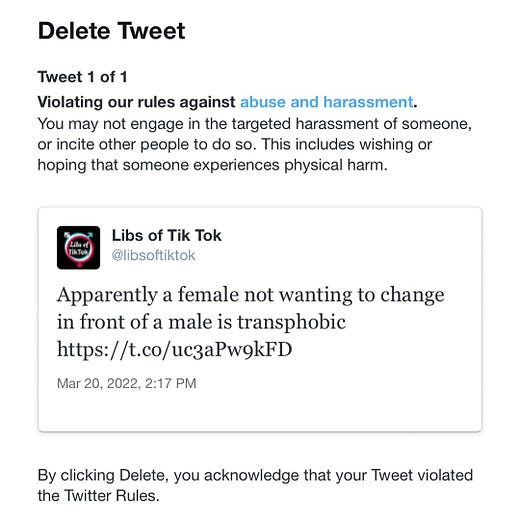

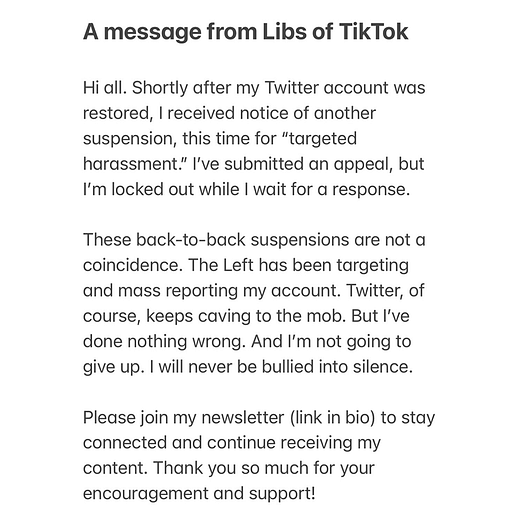

How about another example that I came across during my current Twitter jail time? How is saying that “Apparently a female not wanting to change in front of a male is transphobic” even conceivably defined as abuse?

This is madness. And it happens all the time.

Social media, full of verve and promise in the early days, has not only changed, it’s changed us. It’s changed how we think, how we interact, how we communicate, how we understand the world around us, how we view ourselves, and the kind of Orwellian thought policing we’ve decided we’re willing to put up with.

I don’t think it would be controversial to posit that despite the very undeniable benefits social media provides, the net result hasn’t been particularly positive.

Have you subscribed to The Skojec File yet? It’s only $5 a month, gets you access to our community and exclusive subscriber content. Most importantly, it’s how I support my family and keep providing quality content for you to enjoy!

If you like, you can offer additional support for my work via Paypal or Patreon.

Social Media Has Made Us Stupid

This week at The Atlantic, Jonathan Haight, the social psychologist author of books like, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion,” and “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure,” published a long-form piece on “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.”

And the TL;DR is: social media is the reason why it’s been so stupid, and we’re all part of the problem.

Haidt compares what social media has done to society with the biblical narrative of the Tower of Babel, and the scattering of the human race that came as a punishment for the hubris of its builders. The long version is very much worth your time, and can’t adequately be summarized here, so I want to recommend it in full and then ignore the bulk of it so I can zero in on the parts I found most important. Haidt’s map of the problem traces similar lines to my own nostalgic musings of those simpler, more optimistic days of the early “Web 2.0”:

The early internet of the 1990s, with its chat rooms, message boards, and email, exemplified the Nonzero thesis, as did the first wave of social-media platforms, which launched around 2003. Myspace, Friendster, and Facebook made it easy to connect with friends and strangers to talk about common interests, for free, and at a scale never before imaginable. By 2008, Facebook had emerged as the dominant platform, with more than 100 million monthly users, on its way to roughly 3 billion today. In the first decade of the new century, social media was widely believed to be a boon to democracy. What dictator could impose his will on an interconnected citizenry? What regime could build a wall to keep out the internet?

The high point of techno-democratic optimism was arguably 2011, a year that began with the Arab Spring and ended with the global Occupy movement. That is also when Google Translate became available on virtually all smartphones, so you could say that 2011 was the year that humanity rebuilt the Tower of Babel. We were closer than we had ever been to being “one people,” and we had effectively overcome the curse of division by language. For techno-democratic optimists, it seemed to be only the beginning of what humanity could do.

In February 2012, as he prepared to take Facebook public, Mark Zuckerberg reflected on those extraordinary times and set forth his plans. “Today, our society has reached another tipping point,” he wrote in a letter to investors. Facebook hoped “to rewire the way people spread and consume information.” By giving them “the power to share,” it would help them to “once again transform many of our core institutions and industries.”

In the 10 years since then, Zuckerberg did exactly what he said he would do. He did rewire the way we spread and consume information; he did transform our institutions, and he pushed us past the tipping point. It has not worked out as he expected.

Haidt goes into the switch from using platforms like Facebook to maintain social ties, sharing photos and updates about life with a small group of family and friends, to what came after for many folks: “putting on performances and managing their personal brand—activities that might impress others but that do not deepen friendships in the way that a private phone conversation will.”

It was the “like” and “share” buttons that wound up changing everything, because they gave metrics for engagement that could feed algorithms, and allowed information to be amplified without qualification. It will come as no surprise to anyone that research has shown “posts that trigger emotions––especially anger at out-groups––are the most likely to be shared.”

Haidt details how the transmogrification of social media into a new, viral game, “encouraged dishonesty and mob dynamics.” It also increased polarization and distrust. “The newly tweaked platforms,” Haidt writes, “were almost perfectly designed to bring out our most moralistic and least reflective selves. The volume of outrage was shocking.” And not just in a clutch-your-pearls kind of way, but in a fundamentally-subversive-to-stable-societies kind of way. One of the casualties, he notes, is the destruction of public trust in formerly trustworthy institutions. I think one of the weaknesses in Haidt’s piece is that he doesn’t give enough credit to those who say that there are real reasons to believe that this trust has been squandered. But he isn’t wrong when he notes the upshot: “when citizens lose trust in elected leaders, health authorities, the courts, the police, universities, and the integrity of elections, then every decision becomes contested; every election becomes a life-and-death struggle to save the country from the other side.”

Haidt references the “Hidden Tribes” study performed in 2017-2018 for some telling insights:

the dart guns of social media give more power and voice to the political extremes while reducing the power and voice of the moderate majority. The “Hidden Tribes” study, by the pro-democracy group More in Common, surveyed 8,000 Americans in 2017 and 2018 and identified seven groups that shared beliefs and behaviors. The one furthest to the right, known as the “devoted conservatives,” comprised 6 percent of the U.S. population. The group furthest to the left, the “progressive activists,” comprised 8 percent of the population. The progressive activists were by far the most prolific group on social media: 70 percent had shared political content over the previous year. The devoted conservatives followed, at 56 percent.

These two extreme groups are similar in surprising ways. They are the whitest and richest of the seven groups, which suggests that America is being torn apart by a battle between two subsets of the elite who are not representative of the broader society. What’s more, they are the two groups that show the greatest homogeneity in their moral and political attitudes. This uniformity of opinion, the study’s authors speculate, is likely a result of thought-policing on social media: “Those who express sympathy for the views of opposing groups may experience backlash from their own cohort.” In other words, political extremists don’t just shoot darts at their enemies; they spend a lot of their ammunition targeting dissenters or nuanced thinkers on their own team. In this way, social media makes a political system based on compromise grind to a halt.

[…]

The most reliable cure for confirmation bias is interaction with people who don’t share your beliefs. They confront you with counterevidence and counterargument. John Stuart Mill said, “He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that,” and he urged us to seek out conflicting views “from persons who actually believe them.” People who think differently and are willing to speak up if they disagree with you make you smarter, almost as if they are extensions of your own brain. People who try to silence or intimidate their critics make themselves stupider, almost as if they are shooting darts into their own brain.

[…]

Part of America’s greatness in the 20th century came from having developed the most capable, vibrant, and productive network of knowledge-producing institutions in all of human history, linking together the world’s best universities, private companies that turned scientific advances into life-changing consumer products, and government agencies that supported scientific research and led the collaboration that put people on the moon.

But this arrangement, Rauch notes, “is not self-maintaining; it relies on an array of sometimes delicate social settings and understandings, and those need to be understood, affirmed, and protected.” So what happens when an institution is not well maintained and internal disagreement ceases, either because its people have become ideologically uniform or because they have become afraid to dissent?

This, I believe, is what happened to many of America’s key institutions in the mid-to-late 2010s. They got stupider en masse because social media instilled in their members a chronic fear of getting darted. The shift was most pronounced in universities, scholarly associations, creative industries, and political organizations at every level (national, state, and local), and it was so pervasive that it established new behavioral norms backed by new policies seemingly overnight. The new omnipresence of enhanced-virality social media meant that a single word uttered by a professor, leader, or journalist, even if spoken with positive intent, could lead to a social-media firestorm, triggering an immediate dismissal or a drawn-out investigation by the institution. Participants in our key institutions began self-censoring to an unhealthy degree, holding back critiques of policies and ideas—even those presented in class by their students—that they believed to be ill-supported or wrong.

But when an institution punishes internal dissent, it shoots darts into its own brain.

“[A]nyone on Twitter,” Haidt writes, “had already seen dozens of examples teaching the basic lesson: Don’t question your own side’s beliefs, policies, or actions.”

This is exactly the sort of tribalism I started writing about in the past couple of years. It was particularly amplified during Covidtide, which Haidt also discusses, and was at that time that I realized I was losing much of my original audience because I had zero interest in pseudoscience and conspiracy theory. But neither did I want to truck with those who sought Orwellian solutions to an epidemiological problem. And if the allegations of a stolen election played out in bizarre forms of social and political stupefaction in the secular realm, my zero-tolerance pushback on conspiracy theories like the one that posits Benedict XVI is somehow still secretly the pope was where I first came to loggerheads with people who had previously been openly supportive of my work. This new gnosticism — and I do think the word fits — has a panoply of doctrines to pick and choose from; the only uniting dogma is that you buy into the idea that someone in power somewhere is hiding in the shadows, trying to pull one over on the world, and you’re one of the few who know the real truth. The term “woke” has taken on a decidedly leftist connotation, but it’s really applicable to both sides of this new tribalism — those who consider themselves awake to hidden truths unlike the majority of “sleepers.”

Haidt profiles the way both the Right and the Left have fallen prey to all of this:

The stupefying process plays out differently on the right and the left because their activist wings subscribe to different narratives with different sacred values. The “Hidden Tribes” study tells us that the “devoted conservatives” score highest on beliefs related to authoritarianism. They share a narrative in which America is eternally under threat from enemies outside and subversives within; they see life as a battle between patriots and traitors.

[…]

The Democrats have also been hit hard by structural stupidity, though in a different way. In the Democratic Party, the struggle between the progressive wing and the more moderate factions is open and ongoing, and often the moderates win. The problem is that the left controls the commanding heights of the culture: universities, news organizations, Hollywood, art museums, advertising, much of Silicon Valley, and the teachers’ unions and teaching colleges that shape K–12 education. And in many of those institutions, dissent has been stifled: When everyone was issued a dart gun in the early 2010s, many left-leaning institutions began shooting themselves in the brain. And unfortunately, those were the brains that inform, instruct, and entertain most of the country.

I find it difficult to argue with either of those characterizations.

Some of Haidt’s proposed solutions for social media reform feel half-formed or even ill-advised in contrast to his perspicacity in identifying the problems that created a need for reform. The exception may be his idea that a user verification process should be the gateway to social media access. Despite a very logical concern that this could be used by corporate malefactors or government entities to identify “thought leaders of the resistance” and visit retribution upon them, I think it’s the only likely solution that will cut down on social media abuse, whether by mobs of shitposters or armies of bots. I’m on record as being an opponent of pseudonymous posting on places like Twitter, because my nearly 30 years online has proven amply to me just how much of the abuse is being slung by anonymous accounts. (Full disclosure: I use a pseudonym on platforms like Reddit, because everyone does and not doing so puts the one guy who uses his real name at a big disadvantage; but I wouldn’t be opposed to applying the same rule there.) I recognize that there are some truly worthwhile public commentators who are at real risk if their identities are revealed, but my attitude has been, “Having skin in the game is the cost of admission. If you can’t afford that cost, you’re at the wrong table.”

Haidt proposes what I think is an acceptable middle ground between anonymity and mandatory real names:

Banks and other industries have “know your customer” rules so that they can’t do business with anonymous clients laundering money from criminal enterprises. Large social-media platforms should be required to do the same. That does not mean users would have to post under their real names; they could still use a pseudonym. It just means that before a platform spreads your words to millions of people, it has an obligation to verify (perhaps through a third party or nonprofit) that you are a real human being, in a particular country, and are old enough to be using the platform. This one change would wipe out most of the hundreds of millions of bots and fake accounts that currently pollute the major platforms. It would also likely reduce the frequency of death threats, rape threats, racist nastiness, and trolling more generally. Research shows that antisocial behavior becomes more common online when people feel that their identity is unknown and untraceable.

Whenever I’ve written something like this in the past, it seems I always receive comments to the effect of, “I wouldn’t touch Twitter with a ten foot pole” or “I deleted my Facebook account ages ago.” And while this can certainly be a solution on the individual level, it doesn’t work for the billions who use social media every day, and it’s not practical to expect them to change. Our mode of communication has evolved, and that evolution is irreversible. Those of us who grew up in “The Before Time” are often able to retain our old-world etiquette and perspective, at least in part, but the children growing up today — the ones who have never seen a pay phone, watched a scheduled television program with commercials, seen a culture without ubiquitous smart phone use, or known the feel of a slow, tactile world that isn’t perpetually online — don’t have this perspective. And I don’t believe it can be restored, short of some apocalypse-level event. Our technology is not just compelling, it’s addictive, and it has superseded what came before it. If you don’t believe me, try finding a pay phone some time, or choosing to mail hard copy photos of your kids to your parents when you can just open your phone and click “send.”

There’s more at work than simply a personal decision. If you have a business (or hobby or passion project that involves the public in some way), you probably already know that that a website and social media presence are only optional if you don’t care about success. If you have a content-based business, it’s even more important! If you’re selling something, you need to be where your customers are. If they can’t find you, they’ll go with someone else instead.

We seem to be at a point where we can’t live without social media, but can’t live with it either. It’s making us worse. It’s exacerbating our most undesirable qualities, and keeping us in a state of perpetual conflict. And it’s used by people within our tribes to police us and keep us compliant with the prevailing narrative. Step out of line, and you can expect to get smacked down or excluded from your in groups in a heartbeat. When your parish Facebook group is talking trash about you, there are real-world consequences in play. When you lose your job over your opinions — or can’t get hired because of them — that’s even worse. And cyberbullying sounds weird, but it’s real, and often has severe consequences, especially on teens. So does phenomena like Instagram-induced body dysmorphia. (Yes, that’s a real thing.)

Haidt seems to think that despite the bleak outlook, we may be reaching a tipping point that could take us in a better direction:

[W]hen we look away from our dysfunctional federal government, disconnect from social media, and talk with our neighbors directly, things seem more hopeful. Most Americans in the More in Common report are members of the “exhausted majority,” which is tired of the fighting and is willing to listen to the other side and compromise. Most Americans now see that social media is having a negative impact on the country, and are becoming more aware of its damaging effects on children.

But ultimately, he doesn’t know what it will take to fix it, and neither do I.

I’m ok with having reasonable debates to get to the bottom of topics, but I’m tired of fighting. I don’t want to pick up my phone with the sick feeling in my stomach that a bunch of people probably personally attacked me in the time I looked away from the palantír to do real world stuff. You never know when you’ll go viral for the wrong reasons and invoke the mob. Hell, I just miss the time when we weren’t expected to reply to incoming message on nights and weekends, because that’s just not what normal people did.

We need more real world, slow living. We need more decency with each other, less thought policing, and more freedom and encouragement to color outside the lines. We need to be more offline more often, even if it makes us uncomfortable.

The question is: how do we, as a society, get there from here?

Hey brother, I’m still suspended from Twitter. Four months now because I told someone it was wrong to wish that a persons children would get sick and die. How crazy is that? I miss our interactions on there and I was so glad to get this newsletter. God gave you a wonderful mind and I love reading your thoughts. Thanks for sharing.

As someone born I. 1953, a generation earlier than you, Steve, I recall the old fashioned practice of writing Letters to the Editor of a newspaper or magazine. Anyone who thinks that the Good Old Days were better has obviously never seen UK tabloids at their indescribably vile worst. It was amazing that even more reputable publications produced grotesque errors - which were obvious on the rare occasions when I had personal knowledge of a story. It left me with little respect for the alleged "professional" journalists who wrote this rot.

It is great to be able to contribute my knowledge and insights on stories where I have serious knowledge. I try to be calm and polite, as I am sure that adds authority. And I have learned much from any number of below the line contributers.

The late Malcolm Muggeridge recalled the "unbridled insanity" of most letters to most British editors in the 1950s, so perhaps not much has changed in the deranged bile level. Theodore Dalrymple, as ever, has interesting insights into the world wide shouting competition we can all join.

https://lawliberty.org/which-came-first-twitter-or-the-troll/