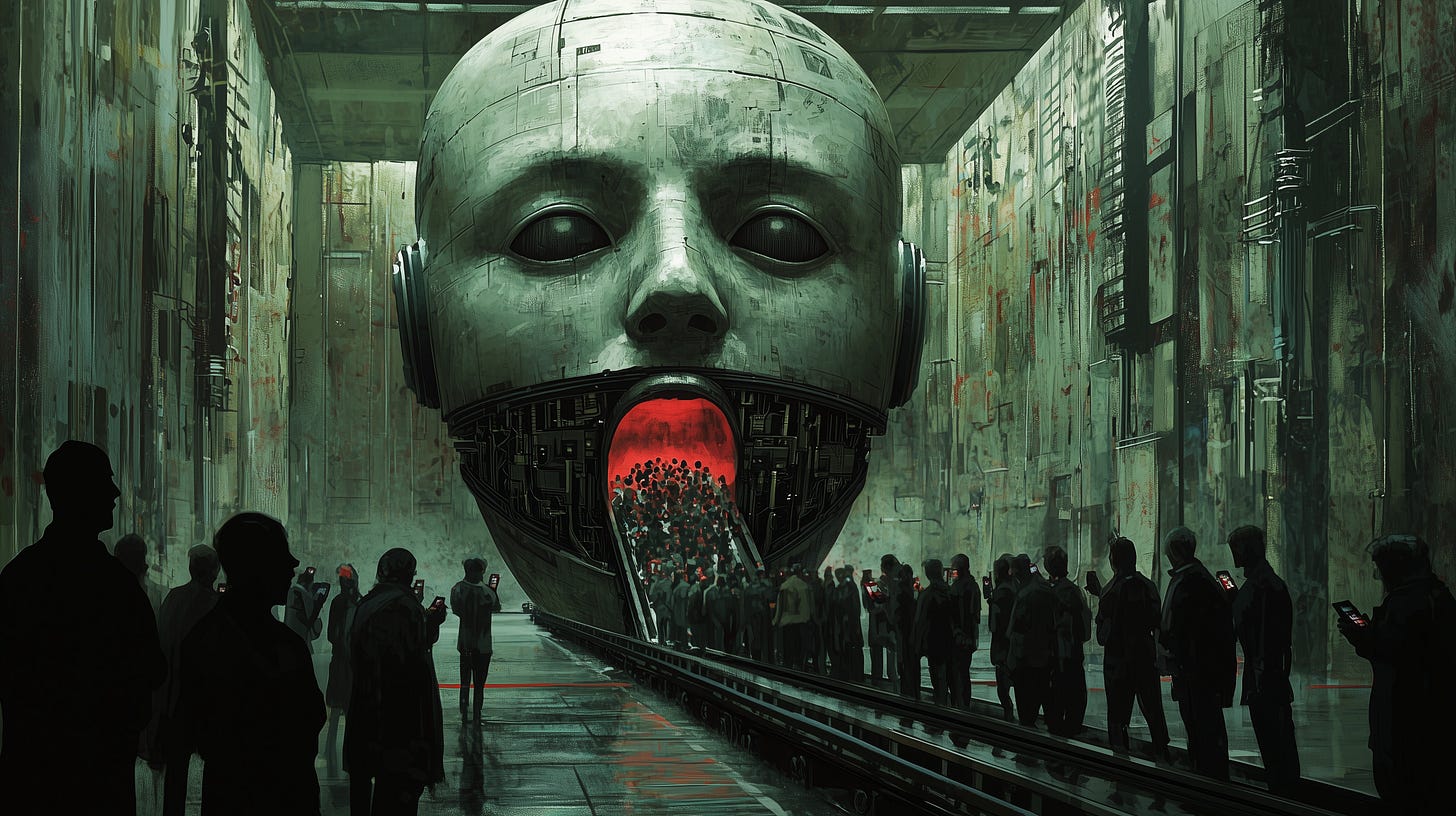

The Algorithm is Eating Us

The following is a free post. If you’d like access to all subscribers-only features, our full archives, podcasts, and every post, you can subscribe for just $8/month or $80 per year, right here:

Writing is how I make my so if you like what you see here, please consider a subscription so I can keep doing this!

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy me a coffee to help keep me fueled up for writing, you can do that here:

Alternatively, I would gratefully accept your patronage at my Paypal. Your contributions have been a huge help during a very financially challenging time. Thank you!

It’s a funny thing, saying the phrase, “The Algorithm.” As you roll it around in your mouth, it tastes by turns esoteric and profound and smart and cliché.

But almost none of us know what it actually means. We construct our mental picture of The Algorithm in broad strokes, like a contour drawing made without looking at the paper. We gain a proprioceptive view of the general shape of the thing, but it’s distorted and featureless.

In other words: our understanding of The Algorithm is functional, but incomplete.

We are vaguely aware that The Algorithm is some gnostic bit of tech that drives our technological experience. It is the cascading green text behind the Matrix, the unseen hand that shows us the posts it thinks we want to see on each and every platform. It re-arranges our Netflix recommendations and our YouTube homepage based on things we’ve previously watched. It picks the next song in our playlist when we run out of pre-selected tunes.

It may as well be referred to as “SilentGPT,” the enigmatic quasi-mind that lurks and watches, like some digital voyeur, learning who we are and what we like and how we interact with things. And then, using formulas and mechanisms we neither know nor understand, it uses this information to try to keep us coming back, looking for another hit of dopamine, like the addicts we have all become.

And yes, if we’re online, we’re addicts. All of us. Our experience has been designed to ensure it.

But unless we belong to the caste of tech priests and know the intricacies of the sacred code, we don’t know what The Algorithm actually is, or where it lives, or how it performs its magic. Our experience of The Algorithm is seamless, unobtrusive, and almost entirely invisible. As we sit at our desks in the morning, sipping coffee and scrolling through our feeds, or lie in our beds at night, watching videos as they come up next in a queue we did not create, we have a tendency to assume that we are in the driver’s seat. It was our fingers that swiped, our choice of who to follow that helped select that content.

This is, of course, an illusion. There’s a lot more to what gets put in front of us than that. Making it feel like it’s our idea is part of the game.

Until now, it’s all been working fairly well. If you have a phone that tracks such things, just take a look at how much time you spend online. The proof is in the data.

Of course every platform has its own algorithm, and not all algorithms are the same. Facebook, for example, has become so aggressive in showing me things it thinks I will like that I grow irritated at its suggestions and log off not long after I jump on. Instagram — a Facebook company — is much the same, tuning the feed in real time based on every interaction. It feels creepy and imitative in a way that shatters the illusion of choice. YouTube can be similarly manipulated, but if you don’t want more videos on how to get rid of back hair after you’ve already figured that out, you can simply delete any related videos from your history, and the recommendations re-adjust.

It is only together, amidst the amalgamated experiences of every different local algorithm that the overarching, symbiotic thing known as The Algorithm comes into being. Like Voltron, it is a machine that is more than the sum of its separate and distinct parts.

“It’s All Junk!”

Lately, I have begun to notice The Algorithm more than usual. Like a veteran alcoholic who has become careless about keeping his habit hidden, The Algorithm has begun to coalesce into something more perceptible, its invisibility cloak shifting into the spectrum of visible light. In much the same way as a gyroscopic toy pushes back against the hand movements of the user, I can feel The Algorithm tugging me in the opposite direction as I attempt to pull away.

If you pay attention, you can feel it trying to distract you, shoving things in your face it believes you’re interested in whether you want it to or not. Maybe you were going to just drop in for a ten-minute check on the news, or to look for something you had saved, and the next thing you know you’ve been scrolling for an hour and don’t even remember why you’re there.

I am reminded of a scene from the 1986 film, The Labyrinth, in which the protagonist, Sarah (Jennifer Connelly), is making too much progress in her quest to find the goblin city, where her baby brother is being held captive. Intent on stopping her so he can keep the little child as his own, Jareth, the Goblin King (David Bowie), coerces a reluctant minion into giving Sarah a magically-drugged peach. In a moment of hunger, she enthusiastically takes it from the weak-willed Hoggle, whom she believes to be a friend.

As soon as she takes a bite, she knows something is wrong. “This tastes strange,” she exclaims in consternation, a look of fear spreading across her face. “Hoggle, what did you do?!”

But as Hoggle waddles away in shame and self-recrimination, Sarah is transported into an illusion of a masquerade ball, where the charming Jareth takes the role of a dashing and mysterious suitor. Sarah is decked out in finery, and she makes her way through the crowd to Jareth, with whom she begins to dance. She has been made to forget that he is her enemy, so cruel as to keep a toddler hostage. At some point, Sarah, who is unusually self-aware, begins to notice that something is wrong. She looks around, and is overcome by the surreality of it all. She pulls away from Jareth and pushes through the crowd, grabbing a chair and hurling it, shattering the glass container of the illusion. She awakes in a seemingly endless scrapyard, where she encounters a character known as “The Junk Lady.”

And this is where the uncanny metaphor for the algorithm begins. When you watch this scene, think of The Junk Lady as an embodiment of The Algorithm: seemingly helpful and benign, but something sinister lies beneath:

Throughout the entire scene, Sarah is trying to recover from the magical hangover that has stolen her memory and sense of place. She knows there is something she is supposed to be doing, but in all the distractions being thrown at her — all pulled from her own likes and preferences and favorites — she struggles to figure out what, exactly, it is. As one of Jareth’s goblins herself, The Junk Lady’s task is not, in fact, to help Sarah, but rather to surreptitiously distract her from the mission to rescue her brother before time runs out.

And for a moment, it almost works.

But then, suddenly, Sarah realizes she has simply gone from one layer of illusion to another, and all of her toys and the comfort of her own bedroom are merely being used to trap her and make her complacent.

How many times a day do we find ourselves starting from a waking dream, only to realize we are wasting time, having forgotten what we set out to do in the first place?

There is much to admire about Elon Musk, as an inventor and industrialist and visionary. In some very important respects, I think his acquisition of Twitter as the de facto public square may have saved free speech, and in so doing, steered our country away from the most self-destructive trajectory it has ever been on. On the other hand, Musk has become a bit like Jareth, The Goblin King, and The Algorithm is his minion. He bought a business for noble purposes, and did so at great expense. Like any business owner who has sunk a fortune into his investment, he wants that business to make his money back. His stated mission has been “to maximize unregretted user-seconds. Too much negativity is being pushed that technically grows user time, but not unregretted user time.”

So The Algorithm feeds us our favorite toys. “Here’s some political news you like, yessss? You like that don’t you?” “Oh, looooook! Here’s that funny video account, you want that don’t you? Yessss.” As we sit there, being buried under a pile of things The Algorithm already knows we want, we may, if we’re on our toes, find ourselves having a very familiar dialogue:

User: “There was something I was looking for…”

The Algorithm: “What the matter my dear? Don’t you like your toys?”

User, realization setting in: “It’s all junk!”

And for us, to shatter the illusion is to return to the real world.

The Internet was a Servant Before it Became the Master

In over 30 years on the internet, I have watched this relatively-young technology grow, develop, improve, and eventually, metastasize. It is still deeply useful, but it has also transformed into something that can hurt as much as it helps.

It is an indispensable tool. A venue for connection. It allows me to share my writing with thousands of people, it allows friends and families to stay in touch, it makes it possible for businesses and artists and communicators to reach customers and colleagues in ways never possible before.

I grew up in a very small, rural town, and the internet, for me, was my ticket out of hicksville. At age 15, I was one of the first 200 users in my county when the internet originally became available in the early 1990s.

But we are a long way from those halcyon days, when AOL was still mailing coasters to every American and the screeching static of modem handshakes was the hallmark of every attempt to get online.

Do you remember what the internet was like before Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube? It’s actually a little bit difficult to think back to how we spent our time online before these platforms existed. We might go to a few websites, check some emails, and then be done. If we were news junkies, we might spend time on a site like The Drudge Report, but there were only so many links you would click; only so many articles you could read, and then there was nothing left to do.

So you’d log off and go back to your normal existence.

In those days, the internet could only be experienced intentionally, not passively. Going online was a process that required specific steps. Data throughput was low, graphics were low quality and video was virtually non-existent.

Blogging was fun for early adopters, but even there, you could only spend so much time in the comment boxes before you ran out of stuff to reply to. Nobody had yet devised the “infinite scroll” technique, where new content loaded as you moved down the page in a never ending display that kept you pinned in place for far longer than your intended stay.

But all of that changed when social media arrived.

In the early days, Facebook was for posting about what you had for lunch and playing Mafia Wars with co-workers and friends and sharing photos of your kids with your relatives. But the iterations came quickly, and before long you weren’t just seeing the stuff your friends were posting, you were the seeing stuff the platform was suggesting.

Every platform had its own algorithm by the twenty-teens, and they became increasingly sophisticated, logging clicks and likes and replies and eventually, even how long you stopped to look at something, or, when camera-enabled phones allowed eye tracking, where you were looking on the screen. As advertising opportunities targeted to increasingly captive audiences grew, so too did the amount of personal data the algorithms collected and hoarded.

These days, every time you like something, you instantly get more of it in your feed. Like The Junk Lady from the Labyrinth, it just can’t stop force-feeding us stuff it thinks we’ll like. And by and large it does a pretty good job, holding up a mirror to our preferences and making us feel like we’re right where we belong. It coaxes us subconsciously, convincing us to keep scrolling, keep clicking, and keep sharing. The ads pile up, and the revenue comes in.

The Metastatic Algorithm

In recent weeks, I’ve begun noticing a shift, especially on X, my platform of choice. Every time I jump on, I feel as though someone is ramming a funnel down my throat and pouring in content I supposedly wish to see.

I like a Coke Zero now and then, it’s true, but I want it by the glass, not the gallon.

The Algorithm has no temperance. It has no moderation or restraint. It no longer provides a sumptuous meal, tailored to the user’s tastes. It will not settle for mere habit, when only compulsion will do. At every stoplight, in every grocery store checkout line, in every quiet moment throughout the day, it wants us reaching for our phones like phantom limbs.

It demands gluttony and nothing less.

And its pet humans have learned how to please it. And profit from its favor. They have adapted to its methods and means. It is a colossal, predatory fish, trailed by countless remora, seeking the scraps left in its wake. Everywhere you look, all you see is engagement farming. More clicks means more money, which requires more outrage, more shock value, and more controversy. As I scroll through my feed, almost everything I see is bait. Even the valuable information is presented in a way that is psychologically designed to maximize its “shareability.” (I’m currently revising the manuscript of a book I wrote about how to do exactly this, because I’m part of the very system I came here to lament. Everyone’s got to eat, and this is how the game is played.)

When we are manipulated into feeling a certain way, we feel compelled to react accordingly. When we look at the boneheaded replies to a controversial post, we want to jump in and start arguing. When we see something that incenses us, and our first instinct is to share it so others will feel what we’re feeling, too. When we see people piling on some poor schmuck who has made some very public mistake, we, too, are compelled to extract our pound of flesh.

Everyone else has an opinion, after all, and why should their voices be heard over our own?

I’ve noticed that I’m having fewer of the actual thought-provoking conversations I go online to have, and more of the exchanges that leave me frustrated, annoyed, and feeling hopeless about the future. Exchanges that cost hours of time that could have been spent more productively.

Maybe it’s the nature of our current state of political discourse. Maybe it’s the state of our extreme political polarization. Maybe we’ve simply reached a terminal phase of grifting clickbait, which becomes less potent over time, and requires more and more dishonesty and exaggeration.

Finding the good stuff in an ever-growing sea of hyperbolic nonsense is no easy task.

The Algorithm was made to feed us, but now, it is feeding on us. It is harvesting our psychic energy, selling us crap we don’t need, pulling us into arguments that go nowhere, and stealing our peace.

It was never supposed to be this transparent. It was never supposed to be so obvious. It was supposed to hide, just below the surface, convincing us to dance to a tune we thought we had composed.

But I can see it now, and I don’t like what it’s doing to me.

The Antidote to the Algorithm

I saw a post recently from a young woman who was getting rid of all internet-connected devices and moving to Europe. I didn’t save the post, so I don’t know what her motivation was, but I suspect it’s related to exactly what I have been describing.

She said that she already sold her computer, and was getting rid of her smart phone. Her next step was to move to Europe and build a life in the real world. She said she would only check her email and look for anything online in weekly visits to a public library. The rest of her life was going to take place in physical reality.

I respect it. Part of me desires it. But I can’t imagine actually doing it.

30 years of being online is a long time. My brain may as well be a cybernetic hybrid, with the computer components housed externally, rather than integrated with my wetware. Neuralink development promises even deeper integration, and despite my concerns, I must admit that this holds some appeal. It will offer real advantages, and I’ve been reading conceptual depictions of such a world since William Gibson invented Cyberpunk.

I can’t imagine being a writer in 2025 and being totally offline. I can’t imagine not having access to the research and media creation tools I use every day. I’ve been typing everything for so long that when I bust out a notebook and pen to take old-school notes to avoid the distractions of the screen, my hand cramps up after only a few minutes. I haven’t used those motor skills with regularity in a very long time, and they have atrophied accordingly. The truth is, I type a hell of a lot faster, and with a lot less conscious effort, than I can write.

And yet, I’ve been growing increasingly aware that forcing myself offline as much as possible is necessary to my creative survival. I’ve been making myself read books (mostly eBooks, I’ll admit) as often as I can. After a few days of doing that, I was even able to push myself one morning to open my Kindle app instead of mainlining the latest news.

The book I’ve been reading is a fascinating novel called, There is No Antimemetics Division. The story is about a mysterious government agency whose job it is to track down and contain certain objects and entities that have the power to make people forget they exist. Yesterday morning, as I was reading it over my coffee, with the nascent strains of this post already coalescing in the back of my mind, I was struck by a connection.

In the following scene (spoiler alert), Marion Wheeler, director of the Antimemetics division, has become aware of SCP-3125, an antimemetic monster that has permeated nearly the entire world, but because of its antimemetic properties, cannot be seen — or at least, not seen and remembered. In fact, it aggressively hunts and kills anyone who becomes consciously aware of its existence. And Wheeler has just realized, on a visit to a secure bunker, safe from the monster’s influence, that she is going to have to find a way to kill it, even if it costs her life.

She does not remember ever visiting this bunker, which was purported to contain SCP-3125, because it is the only place on earth where the monster cannot go. The room has been painstakingly shielded from its influence. But because awareness of the beast means certain death, the protocol for visiting the bunker requires a memory wipe upon departure. No information is ever allowed to leave the room. So she is unnerved to sit there, watching a video of herself that she has no memory of recording, warning her about the danger and difficulty of the task:

Wheeler is at the core of Foundation antimemetic science. She had all the raw data readily accessible. There are extensive written calculations on the walls, but she doesn't need to read them, she can do them in her head. All it took was that slightest push, that slightest suggestion. Staring through the laptop screen, eyes wide and defocused, she understands how it all links together. She sees SCP-3125.

She feels dwarfed by it. She's encountered terrible, powerful ideas before, at every level of memeticity, and subdued them or even recruited them, but what she's picturing now is on another order of magnitude from what she knew to be possible. Now that she knows it's there, she can feel it like cosmic radiation, boring holes in the world with its thousands of manifestations and freely laying waste to anybody who recognises the larger pattern. It's not of reality, not of humanity. It is from a higher, worse place, and it is descending.

The other Wheeler presents her finished diagram. She has drawn a mutated, fractally complex grasping hand with fivefold symmetry. It has no wrist or arm, just five long human fingers pointing in five directions. At its core, there's a pentagonal opening which could be a mouth.

But the diagram was already there. It's plastered across the wall in the background of the video, plain as day, a meticulous collage in green, easily two metres in diameter and showing the same meme complex to a hundred times the level of detail. There are smaller diagrams of different elevations arrayed around it like spores, and its arms are spread wide around the seated Wheeler, who sits directly in front of the mouth, with her back to it.

Wheeler, watching, does not realise this, and does not turn around.

"How do you fight an enemy without ever discovering it exists?" the Wheeler in the video asks. "How do you win without even realising you're at war? What do we do?

SCP-3125 is a very useful metaphor for The Algorithm.

It is pervasive. It is an enemy we barely perceive, if at all. That doesn’t make it any less dangerous. It just means that it is designed in such a way that we don’t notice how it’s changing us.

It is relentless. It doesn’t need to eat or sleep. It doesn’t forget anything. And it’s fighting a war for your time and your focus, which it consumes and converts into resources. Because of this, it wants to hold you captive within the maximum possible number of “unregretted user-seconds,” so it can extract from you what it needs.

And the only way to beat it is not to feed it.

You have to go offline.

The Real World is Boring. It May Also be the Cure.

"That's a piecrust promise. Easily made, easily broken." - Mary Poppins

I have noticed the problem with social media before. I have gone on trips or worked on projects that kept me mostly offline, and have felt the difference.

You can always see the toxicity more when you come back after being away.

But over time, like someone working with antimemetic entities, you forget the very thing that poses the danger. You get lured back in. You become once again entranced. You tell yourself you’ll remember, that you’ll handle yourself differently this time, but you don’t. The familiar pattern is as comforting as an old quilt.

But something feels different this time.

Something more intense, more jarring is developing.

I haven’t even left social media to gain perspective, but I’m feeling its poison in my veins. Over the past week, in lieu of going off-grid, I’ve simply begun pulling back. I use it less, and I try to engage less with content that provokes a kneejerk response when I do.

This is difficult. I am a publisher of online content with no real-life friends anywhere nearby. I work from home in a house full of children and a very busy wife who has little to no bandwidth for the types of abstract discussions on which I like to spend my time. For me, going online is connection, community, a glimpse into the world outside these walls. It’s opportunity, entertainment, and the best way I know how to make a living.

I also have a bad case of FOMO - fear of missing out. It would be easier if it weren’t so useful. I don’t get my news from cable television. I don’t even have cable television. I don’t trust legacy media. I don’t like getting information that’s hours old when things are happening right now.

I remember life before the internet. While it certainly had its upsides, I spent a lot of time being catatonically bored and staring at walls. Or sitting outside and staring at the grass. Or just walking, to nowhere in particular, in silence.

The memories of the Before Time feel quiet, and calm, and slow. They have none of the hectic, always-on quality of everything today. The more you go offline, the easier it gets. There is value in the stillness, with the volume turned down. If you can stay there long enough, you might be surprised what you end up doing with the time.

But there are limits.

You can’t forget the world that you now know.

I don’t have the attention span or fortitude to read and write all day in isolation and I doubt I ever will. I know that boredom is the seedbed of creativity, but a guy can only take so much. I also can’t just post printouts of my writing in my yard.

So I return.

Tentatively, carefully at first, but always on the slippery slope. Before long, I’m back up to my eyeballs in that feeling again, so once again I pull back, or even leave for a while.

Is this life from now on? One foot in, one foot out, circling the drain forever?

I guess I should go online and post this so you can tell me what you think.

And just check the news, real quick…

Here's my cure: no X, no FB, no Instagram, no Whatsapp, no Snapchat, no TIKTOK. TMI, and my eyes cannot take it. Try to pray 2 hours a day. Mothers generally have to pray on the hoof, I am no exception. (Prayer can be meditative or contemplative, or recite the "oldies but goodies".) I do not watch TV, except old VHS tapes with the sound turned off on rare occasion. Why? To help me doze off on the couch (72 almost, I take naps). I watch youtube, often for know how (know how to quilt, know how to sew, know how to fix your own car, know how to make a souffle, know..., you get it). So what do I do instead? I do read online, but I keep it to a minimum: Drudge, Breit, RC Politics, Zerohedge, The Liberty Daily, The Gateway Pundit, Hotair, Townhall. Takes about 30 minutes (read the headlines, you get 90%). Generally, I make myself do leg lifts while reading online or pump iron in a seated position (3 lbs, lots of reps) OR I am eating (quickly, but not so quickly to be unhealthy).

Here is my trick: I keep a running log of my day on paper. Yes, I mark down hour by hour what I've done: what I've eaten, what activity I did, and I start the day out with a list every single day of things I should do. Anything not done in any given day is carried forward to the next day.

I'm not giving up my substacks, though. So keep on writing, Steve.

Here's a youtube channel idea for you, which I've suggested before and you might say: no way, but I think it would have an audience of old ladies and men like me or people who commute a lot as a driver. Summarize the best of X on any given day. "Well, why not read it yourself?" Because my eyes are shot and it's too much information and I am a luddite in some major respects and get frustrated with all these apps and websites, and I'm the driver. So do your "best of" summary, and it can be very limited and eclectic. There may be copyright issues--so you may have to paraphrase your contributors, or get their permission. Could be a deal-breaker. I have to drive a lot and I would listen to that, as I do other "thinker" podcasts (you know, the usual people like Rogan, other thinkers on Spotify). I think it would be a hit. A lot of people are trapped in their cars all day (on many days, I am on a LONG drive, because I travel to help various people and run chores).

If you don’t watch garbage 24/7-the algorithm can’t bother you. If we don’t eat shit food 24/7, we all won’t be so fat. It just takes a little discipline and the bad man will go away.