Untethered

Loss, Freedom, and Family Legacy

The following is a TSF free post. If you want access to our comment box & community, subscribers-only posts, The Friday Roundup, and the full post archives including this one, you can grab all of that for just $5 a month (or even less on an annual plan) by subscribing right here:

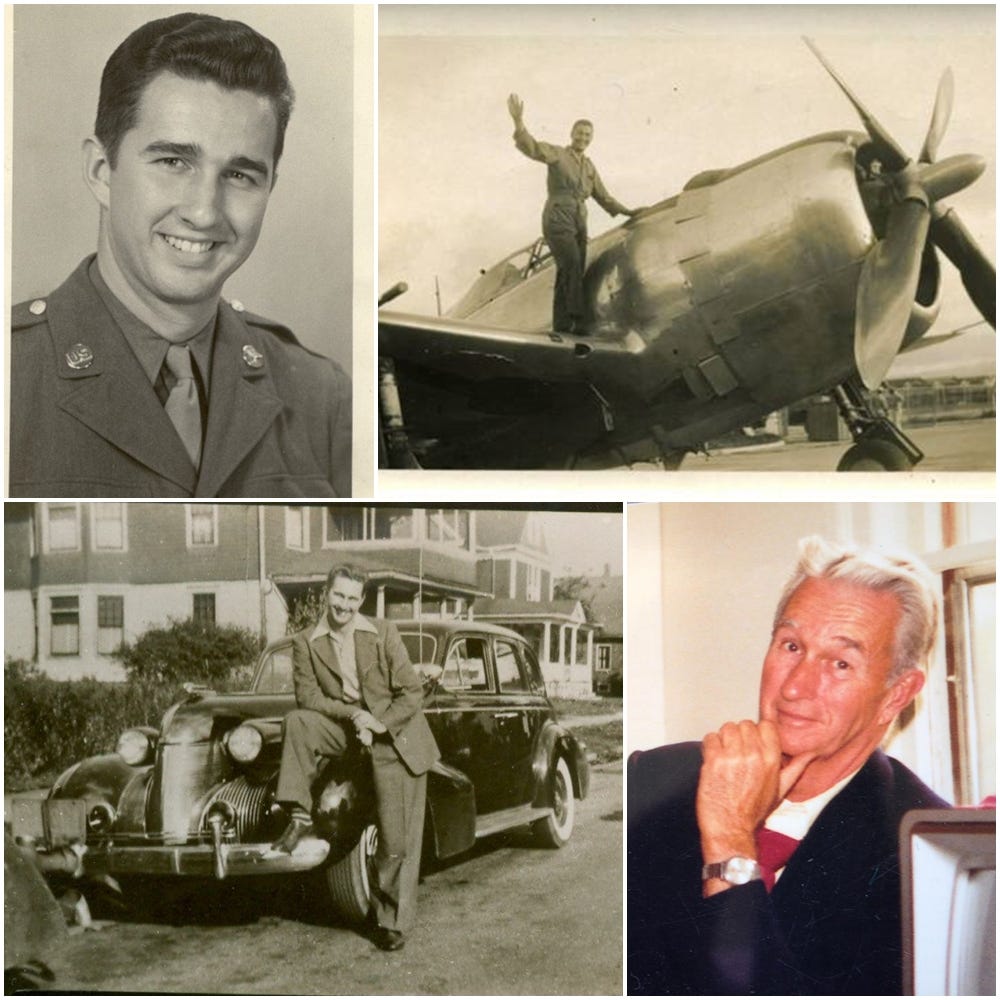

My maternal grandfather, Bill Emmons, died on June 6, 1992. He was just 71 years old.

I was 14, so he seemed much older to me at the time.

I had a little boombox I used to bring with me, because I could record on it. (Even then, I was always making some kind of media.) In the days leading up to his death, and on the day of the funeral, I recorded status updates on cassette tape. It’s interesting to go back and listen to those old clips. To hear adolescent me, with his cringe-inspiring Upstate New York accent (which has long-since disappeared from my voice without me intentionally suppressing it), talking about the emotions he was going through, and the ones he was struggling to process.

“I loved my grandpa.” Younger me said, my voice not yet having fully dropped. “And I’m gonna miss him. And crying’s OK. But I’ve been holding it back so long. I’d just like to go somewhere and just be able to…to cry. As much as I want. But I’m losing my emotion here….”

I remember that feeling, like being emotionally constipated. Like my grief needed to come out, but just wouldn’t budge. I remember going out to the tree fort I’d built in our back yard and just lying on the weathered platform, looking up at the sky, wondering why the tears wouldn’t come. Why I couldn’t feel the depth of loss and grief that everyone in my family seemed to be feeling.

I dreamt about him for years afterward. He was the only grandfather I’d ever known, since my dad’s dad had died before I was born. I knew he was a good man because of how much he was loved, but most of the time I got to spend with him came after he was already suffering from long-term diabetes, a stroke, partial blindness, and a swollen blood vessel in his brain that put pressure on a nerve, causing him to occasionally hallucinate.

“I know there’s not a ship in the living room,” he once said, “but I’m looking at it. I can see it running all the way over there,” as he pointed toward the dining room on the far side of the house from his chair. Another time, he yelled at me for watching something inappropriate when the only thing I had on the television was a live feed of a NASA mission.

He was often stern with me, and it was worse when, as in the example above, it was the fruit of misperception. I was old enough to be annoyed, but too immature to get it. By the time I got to be around him much — my family had lived hours away from my grandparents for the first 11 years of my life, making it only possible to have occasional visits — he was already diminished, and unable to teach me the things you’d like to learn from your granddad.

The first time I realized what kind of man he must have been was when I saw the long line of people coming to pay their respects when he died. During viewing hours over the course of two days, people never stopped coming. Hundreds of them. I was shocked, at one point, to see a girl from my high school in line. We didn’t know each other, but I knew her face. Turned out, her father had worked with my grandpa.

I didn’t know what to think.

My grandfather had not lived a grandiose life. He was one of nine children, born in Binghamton, NY, and died in the same town, having lived there for most of his life, except for a brief stint in West Virginia after the war, where he’d met my grandmother. He had served his country as a Sergeant in the US Army Air Corps during World War II. He’d wanted to fly planes, but he’d been hit by a car while riding his bike as a boy, and it had damaged his vision enough that he had to settle for being a mechanic instead.

But he loved being a mechanic. Loved working on cars. Legend had it that in his golden years, when his vision was bad, he could just listen to cars go by and identify them by the sound of their engines. He met my grandmother because she drove into the gas station he was working at after the war in her Model T, which would have already been a classic at the time.

As the story goes, he asked his buddy, “Wow, do you see that?”

“The car or the girl?” his buddy asked.

“I’m talking about the girl. You can keep the car!” my grandfather said.

He was always buying cars that needed work and fixing them up for sale to help support his own family of eight children. He worked as a mechanic or in auto parts until he physically couldn’t do the work anymore. They were never wealthy, but I never heard them complain about money, either. They had each other, and they taught me, despite their own dysfunctions, what it meant to be part of a family where love comes first.

He was also the kind of man who would stop to help anyone he saw broken down on the side of the road, no matter what he had going on. He was, I realized as I stood there watching hundreds of people come to pay their respects, a man who had touched countless lives, in ways I knew nothing about. It left an indelible impression on me, and it’s one that I still think about to this day.

It was my first glimpse of what real legacy is. I have never wavered in my belief, since we laid him to rest 32 years ago, that the quality of my own life will most accurately be measured by those who mourn my passing because of the ways in which I touched their lives.

And as I type this, just 25 years younger than my grandfather was when he died, I am acutely aware that I have not done nearly enough to measure up.

I was reminded of all of this last week as we buried my father-in-law.

He was a well-known man in his community. He born only 12 years after my own grandfather, and lived in the United States for 78 years, after emigrating in 1946. He spent most of that time in Tucson, Arizona, running his small commercial properties and working as a handyman for friends and family and the members of the Chinese community. Whenever he walked into a restaurant or a store, people knew him. If it was a Chinese restaurant, you’d think he owned the place, the way he’d walk in and start bellowing out greetings and orders in Cantonese. He was an elder in a Chinese association formed to help immigrant workers facing discrimination in business. He had 3 children, 16 grandchildren, and I don’t even know how many great-grandchildren.

We weren’t able to have a wake for him, but he was buried with military honors at the National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona. As I did the head count at the funeral to update the restaurant where we were having the reception, I was really suprised.

Other than my wife and children, only 25 people came. Almost all were family. Several were from my mother-in-law’s side, despite the fact that they divorced over 30 years ago. It was the smallest funeral I’ve ever been to.

I have my theories as to why. After spending the last 7 years with him in our care, 5 of those years with him living in our home, I know as well as anyone how complicated his legacy was. His estrangement from several close family members was not a secret.

But I’m not here to speak ill of the dead. Only to learn the lessons they have to offer.

My wife bore the responsibility for her father’s care with all the grace and magnanimity she could. Despite the fact that in his dementia, he always talked only about how much he loved his sons, almost as though he forgot the daughter who was actually taking care of him was there.

Despite the many disappointments, abandonments, and even betrayals she suffered at his hands over the years. Despite the deep pain she still carries because of these things. None of it stopped her from doing her duty. She gritted her teeth, held her chin up, and relentlessly looked after his best interests until the very end.

And now, after the book of his life has finally closed, with us having been so intimately intertwined with it, we feel rather intensely that the first volume of our own lives has as well.

“I’m untethered,” Jamie said to me this morning. “Even though everything he had is gone, even though he was totally dependent on us, there was just this feeling in the back of my mind as long as he was alive, like there was something there to go back to if I needed to. I know it wasn’t true, but it felt that way. And now, I’m just cut loose. Set adrift. There’s nothing tying me to anything here anymore.”

Arizona, for us, has been this strange, almost mythical place, that always pulled us back. She grew up here and only ever wanted to leave. I came here after graduating college in 2001 and wound up going home several months later, after 9/11 happened. She followed me there, and then together, we moved to Northern Virginia when she got a job in DC. We would wind up getting married there, and spending a number of years living in that area.

But we came back to Arizona over and over, moving here some half a dozen times, each time thinking it would be the last. More than half the time, our primary reasons had to do with seeing to the old man’s care, even when his ingratitude for our efforts seemed too much to bear.

In 2022, after our New Hampshire adventure turned out not to be what we were looking for, we came back to Arizona again, one final time. We put the kids back in school. His dementia having progressed to the point where we couldn’t keep him in our house any longer, we found a care home for Jamie’s dad to live in while we figured out what was next. Eventually, we bought an assisted living home of our own, and when a room opened up, we moved him into it - just a short time before he passed.

Almost like things had come full circle, and closure only came when we put him in the home we purchased to make sure he had a place to live out his final days.

And now, at long last, we’ve been set free.

Except for Sophie, our 18 year old daughter, who is finishing her senior year, the charter school our kids have been attending on and off since 2016 is no longer a good fit. Three headmasters and a lot of staff turnover later, it just isn’t the same environment they started in. Our kids were starting to act like public school kids, which was the last thing we wanted. So we pulled the five younger ones this past semester, and are beginning homeschool.

The housing market here was supposed to correct, but never did. In the area where we live, homes priced at $300/sq. ft. are at the low end of the scale. $600-$1,000/sq. ft. is not uncommon. Imagine paying $1.2 million for a lightly-renovated, 2500 sq. ft. 1960s ranch on a postage stamp lot, and you’ll get the picture. It’s wildly overpriced for our tastes, and not worth it to us to stay.

And this leaves us, once again, untethered.

Once Sophie graduates, we will be fully adrift. The friends we have here are wonderful people I’ve known since college, but whom we rarely see. Our lives and theirs are so busy, it’s hard to make time. When they were younger, our kids used to play together like they were cousins, but even those dynamics have changed. Their older kids are growing up and leaving the nest. They’ll have two in college this fall. Our younger kids are just not as close with theirs, ages and opposite sexes complicating the mix.

Nothing is the same.

We talk about going back. About returning to Virginia, to the place we started our lives together. To the only place my wife and kids have ever called home. Jamie has been feeling a pull to pick up where we left off in 2016.

But it’s different there, too. We’ve visited a bunch of times in the past two years, and it’s changed so much. Our relationships with the people we know there have changed. If we return, it will be on very different terms than when we left.

I’ve come to respect the desert, and to love the West Coast. There is a rugged beauty and a majesty to the Western United States that is unmatched anywhere else I’ve been. But as beautiful as it is, it doesn’t feel like home.

As we talked it through today for the hundredth time, I tapped into my new fascination with all things woo, and managed to identify the problem.

“The energy here is wrong,” I said. “There’s no lifeforce in anything. The desert is too sparse. Too much rock and sand and not enough living things. The places we like here are where they have green grass and mature trees. The places where they do everything they can to make you forget that you’re in the desert. But you can feel it. Something is missing.”

We’ve had a rare run of overcast, rainy days here this past week, and it’s been a balm for the soul. It’s the kind of thing that makes you want to stay, because it’s gorgeous here when it rains. There’s a smell that comes from the resin of the creosote bushes that grow in the Sonoran desert that is released after a storm, and it’s aromatic in the best sense of the word. This morning, mist descended from the clouds over the McDowell Mountains. My wife called from the car to tell me that it looked like something from Lord of the Rings.

“Maybe we just need to take breaks,” Jamie said. “There’s so much development here. So much opportunity. We’ve got ESA funds for homeschool. We’ve got a business here. Maybe we need to take trips to places where we can get our weather fix.”

“Our lives are busy,” I said. “We need weather we don’t have to schedule. I want to be surprised by rain.”

“Or by snow!” she replied.

“Exactly. I want nature to throw stuff at us unexpectedly that just changes your whole mood. I don’t want to have to wait through 278 days of sun to get a good rainy day.”

Our kids tell us all the time that they miss weather, and seasons. They say they don’t want to live here after they grow up.

I don’t want to live somewhere they’re going to move away from when that time comes. I want them to come home to visit. I want them to have a reason to live nearby. As much as I don’t want to move, ever again, I suspect one last big relocation is in the cards.

I think Volume II of the book of our lives, the one that’s just opening to the terror of a blank page, is going to be about legacy. We spent the first half of our lives trying to outrun our childhoods. To deal with our wounds. To figure out who we are. We aren’t really fully done with that. But we’re getting close. And from here on out, the most important thing is the family community we want to build with our kids.

For various reasons, neither of us have that with our siblings or their kids. We didn’t, and don’t, have it with our parents. The family I always wanted to be a part of, the one I felt that I was a part of for a while, growing up, is something we’re going to have to build. You don’t luck your way into a family like that. You have to be intentional about it.

If you’re not, it too easily falls apart.

“We’re all each other have,” I told my kids the other night. “When you guys grow up, I want you to still be friends. I want your kids to play with each other’s kids. I want all the cousins to know their cousins. And I want you all to come home to see us. We want you in our lives.”

I don’t feel like I’ve done much right in my 20 years of marriage. I have been, in many respects, a deeply broken man trying to put himself together again, often at the expense of others. The process has been painstakingly slow. But I know I love my kids, and I don’t ever want to lose them. I know that our oldest daughter lives back in Virginia, and just gave us our second grandchild, and despite the tremendous turmoil in our relationship with her over the past 7 years, we want her to be a part of our life, too. Yesterday was my wife’s birthday, and as I drove Jamie around, doing our errands for the day, mother and daughter were face-timing each other, our 2 year old “baby” in the back seat of our car, her new little guy on her lap. We talked for a long time. It was the closest thing to normal I’ve felt in forever. We were a family again.

Jamie and I are nomad souls. Each for our own reasons, we have both lived untethered lives. But we crave roots. We have become aware of our cultivated lives of instability. We want to build cohesion, and family unity. We want to make a home that is permanent, solid, and stable. One that every child and grandchild can come back to, and feel safe.

We want them to feel as though they belong.

We want to build legacy. We want to know that when our time comes, there are no faces missing from the crowd of those we loved, because we pushed them so far away that they never came back.

It doesn’t matter how many are there to grieve our passing, it only matters that for those who do come, we made their lives better for the time we were able to share.

It’s past time to make it happen. The hour is late.

Steve, I want to recommend a Red State because as we see from the news, things are getting very shaky in the USA. I recommend FL. Okay, you will lose the seasons. So visit VA every fall to see the colors or at Christmas to feel Christmas chills. But you will be in a no-state-income-tax state in FL. IT that will not have a stolen election in 2024. (AZ is having wobbly election integrity in 2022 especially.) Where in FL? Daytona Beach. Cannot be beat. I KNOW THE BEST BEACH IN DAYTONA BEACH. If you wrote me privately, I can make some specific suggestions about an exploratory trip. I bop around FL quite a bit, especially Daytona.