What is Neurodivergence & Why Are We Celebrating It?

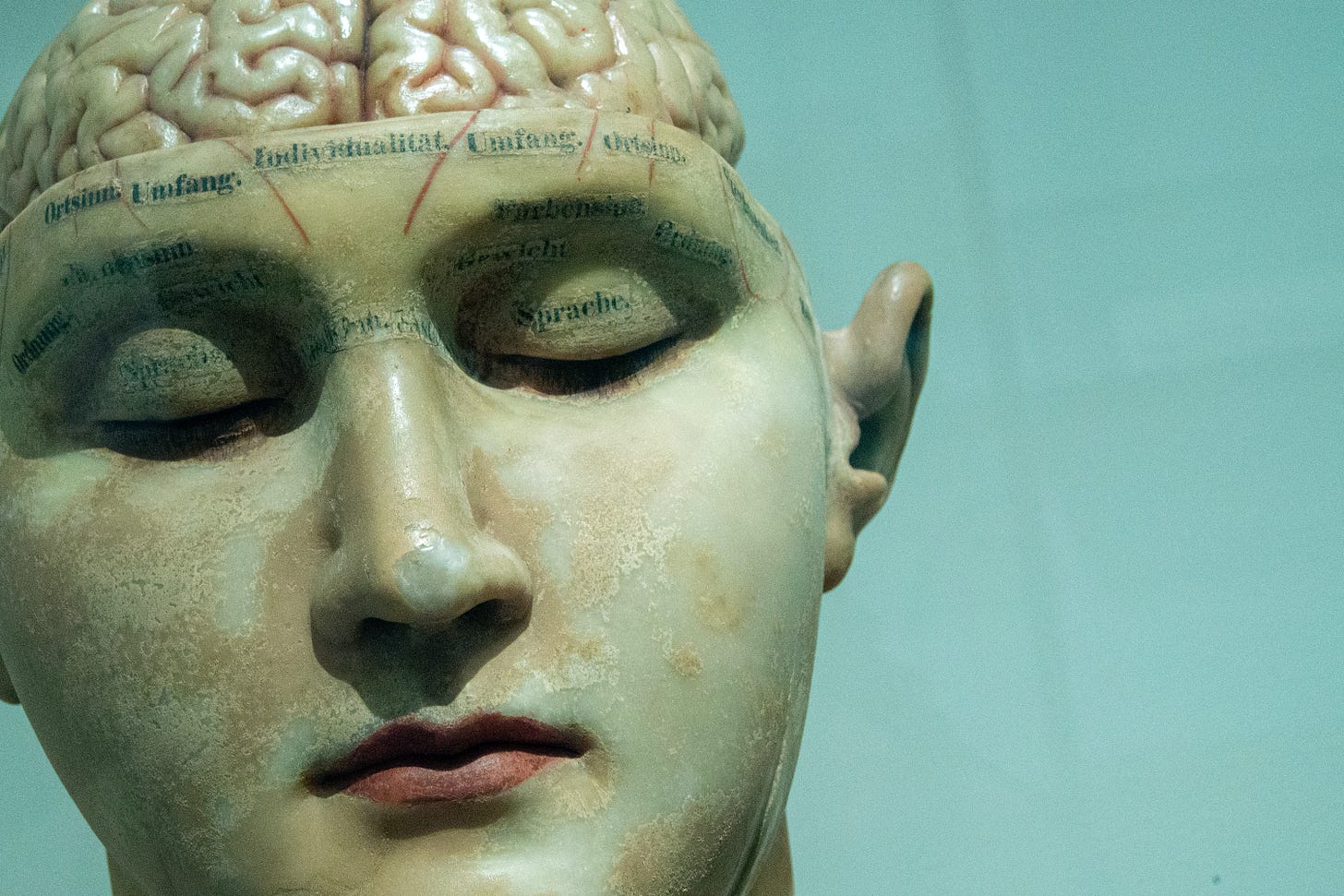

For people whose brains work differently, gifts are often curses, and curses can be gifts.

“Neurodivergent” is a word you see thrown around more and more these days and not, as the word itself seems to imply, in a negative connotation.

I wasn’t aware of the term, at least not consciously, until this week, when the following tweet caught my attention:

For whatever reason, my brain registered the word, recognizing I’d heard it many times before, as a concept I more or less understood without ever having seen it defined. Vague and ephemeral, it filled a particular semantic gap; the sort of thing you know without knowing you know it.

Today, I read a piece by a writer named Freddie Deboer at UnHerd entitled “Mental Illness Doesn’t Make You Special,” and I felt the term lock into place as a new and necessary part of a functioning lexicon. (The pop-vocab words we need to know to be literate in “current thing-speak” is always growing.) And I want to talk more about that piece in a minute, because I think it touches on something really important.

But first, what is neurodivergence, specifically? And why does it matter?

According to AACP publishing, which is “committed to publishing high-quality, inexpensive books for family members, professionals, and individuals on the [autism] spectrum,” a distinction must be made between neurodiversity and neurodivergence:

The definition of neurodiversity is "a concept where neurological differences are respected as a normal and natural variation in human diversity." In other words, neurodiversity refers to the variety of different ways that people's brains function.

The concept of neurodiversity is not new. In the 1990s, a sociologist on the autism spectrum Judy Singer popularized the term. Singer rejected the notion that people with autism are disabled. She believed that their brains just work differently from others.

[…]

Now that we know what neurodiversity is, let's talk about what it means to be neurodivergent. There is no one-size-fits-all definition for neurodivergent. However, neurodivergence typically refers to people who exhibit neurocognitive differences such as the way the brain processes, learns and behaves in comparison to how the neurotypical population does.

Simply put, being neurodivergent means that your brain functions in a way that is different from the neurotypical population. It doesn't mean that you are sick, defective, or abnormal.

In fact, researchers have discovered that neurodivergence can provide a lot of benefits.

This shift in the neurodiversity paradigm has resulted in a new way of looking at neurodivergence. Rather than considering it an illness, practitioners now consider it as a variety of learning and information processing techniques.

According to AACP, types of neurodivergence include:

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (AHDH)

Deyslexia and Dyscalculia

Dyspraxia

Tourette Syndrome

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Psychosis and Schizophrenia

These categories obviously cover a lot of ground, making “neurodivergent” something of a Swiss Army Knife term. But atypical mental states do exist, and are arguably increasingly common, so we’ll work with it.

Now let’s take a look at Deboer’s piece. [Full disclosure: I’ve changed the book link in the following from a UK store to my own US-based Amazon Associates account, for which I am paid an infinitesimal commission on any sales]:

Marianne Eloise wants the world to know that she does not “have a regular brain at all”. That’s her declaration, on the very first page of her new memoir, Obsessive, Intrusive, Magical Thinking. The book catalogues her experience of a dizzying variety of psychiatric conditions: OCD, anxiety, autism, ADHD, alcohol abuse, seasonal affective disorder, an eating disorder, night terrors, depression. By her own telling, Eloise has suffered a great deal from these ailments; I believe her, and wish better for her. But she would prefer we not think of them as ailments at all. And that combination of self-pity and self-aggrandisement is emblematic of our contemporary understanding of mental health.

There’s a cynicism in Deboer’s piece that shows up right out of the starting gate that leaps out in that last sentence. When I first read it, I was open to the idea that it was deserved — after all, we’re nothing if not a culture in the throes of self-love manifested as grotesque self-promotion — but I don’t think it’s entirely fair, and it colors his overall view of the phenomenon.

He continues for a couple of paragraphs, skeptically, at times snarkily offering anecdotal examples of people who see their neurodivergence as a net positive.

And then he circles back to Eloise, for the first time making his cynicism stick to something deserving: a portrait of youthful self-indulgence and self-obsession that is all-too-recognizable to internet denizens of the 21st century:

Against this backdrop, Eloise is a marketing department’s dream come true: hers is a story of the young, beautiful, dysfunctional — and successful. Eloise is the perfect 21st-century woman, from a certain internet-enabled philosophy of human affairs. She is an admirer of witchcraft and believes that women have a mythical connection to water. She does a lot of drugs and becomes bisexual. She uses Tumblr and travels the world, vacationing in Lisbon and the south of France, and moves to Los Angeles to be an actor, taking care to embed that period of her life in a self-defensive patina of irony. She lives an enviable life of obvious socioeconomic privilege, which she does not have time to recognise, as she’s too busy cataloging her psychiatric maladies.

She crams them into every last anecdote: apparently nothing happens to her that she does not ultimately attribute to those maladies. Eloise’s love of swimming as a child is, for instance, laboriously explained in terms of her neurodivergence. I’m talking thousands of words. It seems never to have occurred to her that a love of swimming is not exactly rare among children, or that she doesn’t have to justify her joy at being in the ocean by making it “deeper”. Again and again, she holds perfectly mundane attitudes and behaviours up to the reader and says “Isn’t this special?”

[…]

It is perhaps comforting to see every last detail of one’s life as the product of some uncontrollable force. “I am this way because I was born this way,” Eloise writes, in a remarkably bald denial of personal responsibility. As a pawn of the various interior forces that do combat in her brain, she is adamant that there is nothing wrong with her, that her suffering is all in service to some deeper way to live, and that she is proud of the very conditions she asks us to treat as a perpetual get-out-of-jail-free card for her behaviour.

The implication is that the neurodivergent might just be better than other people. As with introverts, social media users have developed a discourse around neurodivergence that is nakedly self-celebratory, a bragger’s genre. Eloise has clearly endured a great deal of hardship, but like her culture she seems to feel that this hardship can only be given meaning by being woven into a journey of self-actualisation. Eloise writes that her life is “underpinned and ultimately made whole by obsession”. Can you imagine a sadder statement: an adult telling you that there is nothing to distinguish her or give her value but her psychiatric conditions, conditions she shares with millions of others?

The thought floated through my mind as I was reading all of this, despite noting the validity of Deboer’s criticisms, that perhaps those who are neurodivergent and proud of it are merely making lemonade out of lemons. They were dealt a bad hand, and they’ve chosen to see it as a net positive — although it doesn’t let them off the hook for claiming a multifaceted victim status that excuses their every poor choice, or for lobbing the accusation of “stigma” at everyone who doesn’t buy in.

On the flip side, I wondered what the alternative mentality would look like. What would someone who didn’t try to turn their neurodivergence into a hashtag do? I didn’t have to wonder for long. Deboer offered up his grim view on a platter:

What I find tragic about those who buy into the neurodivergence narrative is that they become their illnesses. And yes, there are alternatives. Eloise and people like her seem never to consider one of the possible ways that they could have dealt with their myriad disorders: to suffer. Only to suffer. To suffer, and to feel no pressure to make suffering an identity, to not feel compelled to wrap suffering up in an Instagram-friendly manner. To accept that there is no sense in which her pain makes her deeper or more real or more beautiful than others, that in fact the pain of mental illness reliably makes us more selfish, more self-pitying, more destructive, and more pathetic. To understand that and to accept it and to quietly go about life trying to maintain peace and dignity is, I think, the best possible path for those with mental illness to walk.

And all I could think was, “what a dour and pessimistic way to deal with a difficult reality.”

I don’t think pain should be painted in pretty colors and worn as a badge of honor, or flashed like a signal for attention and affection, though the latter thing is certainly understandable, since one of the core components of deep pain is a feeling of loneliness: “I suffer in a way that others do not understand. They cannot feel what I feel, and I hide it behind this smile, this attempt at normalcy.”

“What can I not doubt?” asked Jordan Peterson in his book, 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote to Chaos. “The reality of suffering. It brooks no arguments. Nihilists cannot undermine it with skepticism. Totalitarians cannot banish it. Cynics cannot escape from its reality. Suffering is real, and the artful infliction of suffering on another, for its own sake, is wrong.”

“If the worst sin is the torment of others,” he continues, “merely for the sake of the suffering produced— then the good is whatever is diametrically opposed to that. The good is whatever stops such things from happening.”

Suffering is an inescapable reality. But it needn’t merely be swallowed whole. That is likely to create isolation, resentment, and all too often, a person who wants to visit their own suffering on the world.

Instead, suffering can serve as a catalyst for transformation. Peterson again:

If you decide that you are not justified in your resentment of Being, despite its inequity and pain, you may come to notice things you could fix to reduce even by a bit some unnecessary pain and suffering. You may come to ask yourself, “What should I do today?” in a manner that means “How could I use my time to make things better, instead of worse?” Such tasks may announce themselves as the pile of undone paperwork that you could attend to, the room that you could make a bit more welcoming, or the meal that could be a bit more delicious and more gratefully delivered to your family. You may find that if you attend to these moral obligations, once you have placed “make the world better” at the top of your value hierarchy, you experience ever-deepening meaning. It’s not bliss. It’s not happiness. It is something more like atonement for the criminal fact of your fractured and damaged Being. It’s payment of the debt you owe for the insane and horrible miracle of your existence. It’s how you remember the Holocaust. It’s how you make amends for the pathology of history. It’s adoption of the responsibility for being a potential denizen of Hell. It is willingness to serve as an angel of Paradise.

One way suffering can be alleviated is to share in the suffering of others. To tell them that you understand their pain. To find the upside in the downside. To say, “yes, you have this tremendously debilitating thing that you are enduring, but look at what you have done with it! Look at how your pain has made you strong, has taught you empathy, has sharpened your wits, has deepened your gratitude for what is good in life.”

Even if the Eloise’s of the world are self-indulgent; even if their flaunting of neurodivergent attributes feels like a play for sympathy and attention, there is a real reason to believe that those who suffer from neurodivergence actually do derive something special in many cases. I am a firm believer in the idea that everyone’s strengths are also their weaknesses. That our gifts, or our curses, are double-edged swords. Isn’t it often the case that our pet sins are the flip side of our greatest assets?

I’ve been wanting to write about billionaire industrialist Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter since it first came to fruition, but in the service of that essay, I decided that I first wanted to learn more about. I’ve been reading his biography, written by Ashlee Vance. In one section, Musk reveals some of his own unique gifts: his unusual ability to hyperfocus, and to clearly visualize complex scientific concepts:

At five and six, he had found a way to block out the world and dedicate all of his concentration to a single task. Part of this ability stemmed from the very visual way in which Musk’s mind worked. He could see images in his mind’s eye with a clarity and detail that we might associate today with an engineering drawing produced by computer software. “It seems as though the part of the brain that’s usually reserved for visual processing—the part that is used to process images coming in from my eyes—gets taken over by internal thought processes,” Musk said. “I can’t do this as much now because there are so many things demanding my attention but, as a kid, it happened a lot. That large part of your brain that’s used to handle incoming images gets used for internal thinking.” Computers split their hardest jobs between two types of chips. There are graphics chips that deal with processing the images produced by a television show stream or video game and computational chips that handle general purpose tasks and mathematical operations. Over time, Musk has ended up thinking that his brain has the equivalent of a graphics chip. It allows him to see things out in the world, replicate them in his mind, and imagine how they might change or behave when interacting with other objects. “For images and numbers, I can process their interrelationships and algorithmic relationships,” Musk said. “Acceleration, momentum, kinetic energy—how those sorts of things will be affected by objects comes through very vividly.”

Vance’s book was published in 2015, a full six years before Musk would reveal in a Saturday Night Live monologue that he has Asperger’s Syndrome - otherwise known as Autism Spectrum Disorder.

In an interview with TED Curator Chris Anderson earlier this month, Musk admitted that his work may in fact have a link to the unusual functioning of his mind, saying that he “found it rewarding to spend all night programming computers, just by myself. … But I think that is not normal.” He also told Anderson that he “became ‘obsessed’ with physics and trying to figure out the meaning of life.” The more I read about him, the more clear it becomes to me that Musk’s unique talents are the function of a neurodivergent way of thinking, of acting, of processing information and relating to other human beings — one that has both made him the richest and one of the most ambitious and most successful men in history, but also deeply challenged in many of his interpersonal relationships. His way of thinking, even about love, comes across as deeply transactional:

At this time, Musk had just split from his second wife, the actress Talulah Riley, and was trying to calculate if he could mix a personal life into all of this. “I think the time allocated to the businesses and the kids is going fine,” Musk said. “I would like to allocate more time to dating, though. I need to find a girlfriend. That’s why I need to carve out just a little more time. I think maybe even another five to ten—how much time does a woman want a week? Maybe ten hours? That’s kind of the minimum? I don’t know.”

Imagine trying to fit the parameters of love into a spreadsheet!

Have you subscribed to The Skojec File yet? It’s only $5 a month, gets you access to our community and exclusive subscriber content. Most importantly, it’s how I support my family and keep providing quality content for you to enjoy!

If you like, you can offer additional support for my work via Paypal or Patreon.

In a podcast this month with Curt Jaimungal of Theories of Everything, Garry Nolan, an extraordinarily accomplished scientist, inventor, and Professor in the Department of Pathology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, talked about certain unusual workings in the human brain as relates to those known as “experiencers” — those who have seen or interacted with UFO/UAPs. During the discussion, he touched on the unique cognitive abilities of people with conditions like autism and schizophrenia:

Garry Nolan: We looked at schizophrenics and autism individuals because you know on the far end in the positive, in the fully positive sense of schizophrenics, is that often they can be very creative individuals. Because their minds let's say range a little bit further than than than others.

Curt Jaimungal: They see or make connections that others don't.

GN: That others don't. Exactly. And that's really the heart of intuition, you know, finding disparate datas and showing that they actually have a hidden connection behind the scenes.

And then on the other side of the of the… let's say problem, are autistic spectral disorder of which there are many different types of of autisms. But certain autistics, as you probably know, can be extremely high functioning and they have, again, almost… not a form of intuition, like they're, “Oh, I see things that other people don't,” it's they can come to conclusions that are remarkable, like mathematical conclusions, all right, people who are, you know, you can ask them what the square root of some extraordinary number is and they go like that [snaps fingers]. How, where, and why… how do they do that? What's the process in their brain that allows them to do that? So as it turns out that if you look at the MRIs of such individuals one of the areas of the brain that's called out repeatedly in both of them but in different places is the caudate putamen. There are what we would call at least from our, let's say ‘normative’ standpoint, defects in their caudate putamen, you know not, like wholesale rupturing or anything like that but you know smaller regions or things that seem to be… have gone wrong.

CJ: So it's a diminution of the caudate putamen, or is it an enlargement?

GN: Just, no, neither. Just kind of, let's say dysmorphias. Dysmorphias. Just kind of, like, changes and you know, in one sense if it's any of these things and I don't know that all of them or any of them are, or which of them are, if it's genetically determined it's evolution trying out something new. Because if it were a successful mutation that helped both that individual and their…let's say genetically related group succeed or compete better than others, it will be over the course of time selected for. And in a positive sense.

[…]

[W]hen we ever — and I'm not sure we're ever going to do it in the in the short term —when we get around to doing this with experiencers, or frankly, different classes of individuals with different kinds of extraordinary mental abilities — and by this I mean things like math or, you know, uh music, or etc., you know, are there brain structures associated with these, you know, high functioning individuals that you can call out? Because that tells us… it's not because you want to know what your child is the day they're born: are they going to be a musician, or a mathematician? But you, by doing this, begin to learn about how the brain is actually functioning. So that with these now, what are public data sets, that you can download off the net that have been vetted, people have been classified according to their intellectual capabilities, etc., now you can begin to show that certain — and this is one of the papers that we're just submitting — that certain brain structure organization sizes and tracts between them are, appear to be correlated with certain kinds of intelligence or certain kinds of abilities. And you know we're not the only ones doing it, not by far, but I haven't seen many papers yet that are taking it the same approach that we are with these automated segmentations. But you know, it's so easy to do that I expect there to be an explosion of research in this area. Because it's going to tell us something about how the brain is operating.

If you’ve never seen the kind of exceptional things that some autistic people can do, this short video about an autistic man’s artistic capabilities is fascinating:

Here’s another, from a musical perspective. A description in the video notes that “Lewis-Clack was discovered to be a musical savant. Even though he cannot see, or read music, he only needs to hear most songs once to play them back perfectly.”

There’s a moment in the video about Lewis-Clack where he says he is going to play a song in the style of Mozart. But did you know that many believe Mozart himself to have been on the autism spectrum? This belief, and Lewis-Clack’s own ability to memorize and play music he’s only heard once, helps to make sense of a story I heard in college about how Mozart, at the age of 14, walked into St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, where he heard a particular Mass composition that was uniquely beautiful. The piece was played only on special occasions, and the sheet music was not allowed to be taken out of the building. And yet, after hearing it performed just once, the adolescent Mozart went back to his lodging with his father and wrote it down note for note. We have his prodigious mental gift to thank for the fact that the piece in question — Allegri’s Miserere — is now widely known. And it’s an absolutely stunning composition:

At this juncture, I feel that I should explain that my own interest in this topic is both sociological — I want to know if whether neurodivergence should be celebrated or merely suffered, and in what balance — as well as personal.

I am not on the autism spectrum, nor am I a world-class artist or musician. I am, however, someone who falls within the category markers of neurodivergence. Although it seemed to fall rather short of being a differential diagnosis, in my 20s, my family physician diagnosed me as “probably” having both OCD and ADHD, at which time I was promptly prescribed a class of drug known as a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI), which I took for a brief time. I ultimately quit the drug cold turkey — something you’re not supposed to do, with good reason. (The room felt like it was spinning for days, and I’d been on it less than two months.) But I knew I needed to get off the medication. It was making me into an emotional zombie. In a sense, I felt that it was taking away not just the more volatile parts of my temperament and those that caused me so much anxiety, but also the things that made me me.

I’ve written in the past about my struggles with anxiety, anger, and depression. I am firmly of the belief that in addition to other environmental childhood factors, my half-heartedly diagnosed neurodivergent conditions, particularly the OCD (which is known to run in my family), are major contributors to the anxiety and neuroticism that have plagued me for most of my life. If you have a brain that tortures you almost constantly with obsessive or intrusive thoughts, if your internal monologue is one of ever-present chaos, if you feel guilty about random, sometimes disturbing things you can’t help thinking but also can’t just let drop, you know what I mean. For those who do not suffer from such conditions, much of this probably sounds bizarre. Comedian Bill Burr offers a humorous take on such thoughts — which everyone has to some degree — that glosses over the self-torture that often accompanies them in people with OCD who can’t let them go. For what it’s worth, I still find his treatment hilarious:

These and other aspects of neurodivergence are, I think it’s fair to say, unqualified negatives, and I wouldn’t wish them on anyone —although I have sometimes wished people in my life who have to deal with me could live a day with my brain so they could understand why I am the way I am. (Have I mentioned that my wife is a saint?)

But as with the Mozart story above, there really are benefits to thinking differently, too. The flip side of my not being able to forget things you wish you could stop thinking about is outstanding recall of certain kinds of disparate data, forged together in a weird pattern recognition that helps me sort out signal from noise. I can’t sit quietly and think my way through a problem because my brain is like a noisy train station, but because of this, I’ve learned to write my thoughts down to give them structure and form, drawing them out of the hot, kinetic soup of neurons firing uncontrollably to form a cohesive image, not unlike an immersion 3D printer.

Come to think of it, I’m not sure I would have ever become a writer if the process of writing didn’t calm the raging storm inside my head and give me a mechanism to attain clarity of thought. When I am “in the zone” on a piece of writing or research or creative project, my normal distractibility toggles over to a flow state so deep I’m mostly unaware of the passage of time, sitting for hours working at a single task as long as it holds my interest. I have found that I am also deeply intuitive (an ability research is also beginning to link with the caudate putamen), with a near-instantaneous ability to assess people or situations I encounter, and with uncanny accuracy. In general, I am also strongly creative, with aptitude in several artistic modes, though none as developed as my writing. I’m very fortunate that I live in a time where it’s possible to make a career out of these things. My skillset rapidly drops off in the area of anything very practical.

All of this is to say, I can tell you from personal experience that there are both upsides and downsides, though the scales never truly balance. I wouldn’t exactly celebrate the conditions that seem to enhance my gifts. At this point in my life, if given a choice, I think I’d have preferred to have enjoyed a lifetime of average normalcy over whatever exceptionalism I’ve had, tainted as it’s been with such difficulty and interior suffering. But I’m also grateful for what I can do with what I’ve been given, and I’m not going to fail to make the most of it. The upside, frankly, is one of the only things that makes the downside bearable.

The first time I realized I was not alone in my weirdo ways was when I read father-of-cyberpunk William Gibson’s 1996 novel Idoru, and saw the following description of one of the main characters, Colin Laney. Fictional or not, his mind sounded all-too-familiar. It was an epiphany:

Laney was not, he was careful to point out, a voyeur. He had a particular knack with data-collection architectures, and a medically documented concentration-deficit that he could toggle, under certain conditions, into a state of pathological hyperfocus. This made him, he continued over lattes in a Roppongi branch of Amos ‘n’ Andes, an extremely good researcher.

[…]

The relevant data, in terms of his current employability, was that he was an intuitive fisher of patterns of information: of the sort of signature a particular individual inadvertently created in the net as he or she went about the mundane yet endlessly multiplex business of life in a digital society. Laney’s concentration-deficit, too slight to register on some scales, made him a natural channel-zapper, shifting from program to program, from database to database, from platform to platform, in a way that was, well, intuitive.

And that was the catch, really, when it came to finding employment: Laney was the equivalent of a dowser, a cybernetic water-witch. He couldn’t explain how he did what he did. He just didn’t know.

I feel this way so much of the time. For many who are neurodivergent, not knowing the how or the why of our gifts or the way to get off the crazy train is a huge, ongoing challenge. It’s often easier to seek solace in self-medication than to risk a gauntlet of careless, underqualified healthcare professionals who just want to write you a prescription and move on. If you can manage the monster in your head without losing yourself, it seems safer than, say, suffering what Jordan Peterson went through when he tried to get off of prescribed benzodiazepines — a process that landed him in a coma, and very nearly killed him.

Of my own neurodivergent conditions, not one has ever been elevated by any healthcare or therapeutic professionals I’ve spoken with to the psychiatric level. There is a separate but related conversation worth having about the current view of mental health both professionally and societally. But whatever its indiscretions today, it’s arguably better now than in the age of the cruel and casual lobotomy — a practice that was common just 20 years before I was born. Had that barbarism persisted, I wonder, would I, too, have been subjected to an icepick to the brain? Based on nothing but pseudoscience and hubris? It does make me wonder how much more effective, or damaging, the pharmacological ice picks of our day really are.

So I’d argue that while yes, neurodivergence can take the shape of excuse-making or attention-seeking behavior, it’s easier, too, and certainly better, to try to find the silver lining in the cloud of a condition you can’t escape, than to merely “accept that there is no sense in which your pain makes you deeper or more real or more beautiful than others, that in fact the pain of mental illness reliably makes us more selfish, more self-pitying, more destructive, and more pathetic.” Looking for the bright side should never come at the cost of endangering others. (Schizophrenia and psycopathy fall on the darker end of the neurodivergent spectrum.) But for heaven’s sake, how much harm can trying to turn your weakness into a superpower actually do? Better wishful thinking that might actually crystalize into some real good than mere acceptance that you are cursed so you can recede into the darkness. As a commenter on the Stephen Wiltshire drawing video I linked above said, “Turning your disability into an ability is what makes us all human.”

I think that’s a beautiful sentiment. The alternative, in my opinion, is alarmingly bleak.

Steve, this is one of your best essays ever! I have had OCD and ADD my entire life and at various points thought I would loose my mind or descend into chaos. Thank God, nether has happened. Indeed, at 66 I can look back on an exterior life that has had a good impact on many, and an inner life that, while often frightening, has been the source of much creativity, empathy and intuition. I've heard it said that had SSRIs and SSNRIs been developed in the 14th century (when artists and writers began to break out of narrowly defined parameters) we would have had little great art or literature in the modern age. To be honest, I've used Effexor (an SSNRI) for years and have no plans to stop. However, I fear that I might well have been more creative, empathetic and intuitive had I "bit the bullet" and navigated my condition without medication. Thanks again for bringing this subject into the light.

I actually have a lot to say about this very subject but I will be hampered in expressing it by my own autism spectrum issues. This will be tldr. It runs in my family such that we cannot tell whether my biological children exhibit spectrum issues because they are autistic or because they were raised by an autistic mother. My eldest son is definitely a full blown Aspie, the others exhibit social anxiety and miss social cues but are less “neuro-divergent”. All of us, including my husband, have the ability to make syntheses across disciplines, to memorize and correlate information unusually quickly. We think and talk faster than other people. We are not dramatically accomplished geniuses but we are all smarter than average and that has helped smooth out some of the issues being so different has caused.

Social situations have been nightmarish for all of my 60 years. I gave up completely quite a while ago, but not before experiencing a crushing load of disappointment and hurt from nearly every interaction, everyone that I ever considered a close friend, acquaintances, and my own mother and sisters. The power to wound me which I ceded to others was enormous. I have an excellent marriage of 40 years, close relationships with all my children and grandchildren, and that is it. I do miss friends that I managed to make for brief periods of time, but I was never as important to them as they were to me and I always came to see that I was the one on the giving side all the time, still the little girl offering a quarter to the neighborhood bully to leave me alone. I think this is true of many autistic people, they have adult brains as children and they don’t change much as they grow older.

I remember being bored out of my mind as a child in a house with few children’s books, a grocery store encyclopedia, and bizarre medical handbooks describing foul tropical diseases complete with grainy photos. I taught myself to read all these fluently by the time I was three. I was the cuckoo in the nest always. The forum for Asperger’s syndrome, wrongplanet.net, is so perfectly named. I always felt like everyone else was speaking a foreign language, designed to keep me out.

I have made a life for myself and my husband by raising a large family in a very home centered way, home as a therapeutic refuge from the world. Creating obligations to children and now grandchildren to keep me from running away from the pain in a permanent way. It is a haven that I am afraid we are denying future generations of Aspie women. The modern idea that girls with high functioning autism are really boys is the most insane and misogynistic thing I can imagine. I am afraid that the culture will take the very women who are wonderfully suited as companions, wives and mothers and convince them that this is not for them. Just because Asperger’s has been described as the “extreme male brain” doesn’t turn girls into boys! Nerdy boys are attracted to Aspie girls, they share interests in common and my sons have commented on how quickly girls like me got snatched up when they were in college. Traditional courtship patterns where boys make the advances clarify things for girls who aren’t sure how social cues work. I never had the problems getting along with boys in college that I have always had with girls and women.

The primary premise of the articles which started your essay seems to lump autism in with actual mental illness diagnoses. This is one of the biggest fallacies of modern times, that claiming neurodivergence gives you a pass as far as mental illness is concerned. A person can be severely bipolar, schizophrenic, etc., but if it is framed as gender Dysphoria or other trendy labels you get a sticker and fifteen minutes of fame instead of treatment. People with severe issues of self destruction are given the tools to permanently disfigure themselves instead of getting the therapy they need. These trends have completely destroyed what little credibility psychology had as a science.

I do not think neurodivergence needs to be celebrated. Society cannot continue to celebrate every fractal. Who has the energy to care about this? The emphasis on high functioning people as having “so much to offer” loses sight of the far larger group of severely disabled autistic children and adults who are hidden from society at large. While attention whores plead their special cases what happens to the ones who graduate from special ed at 18 or 21 to a lifetime isolated in their childhood homes, dependent on aging parents who worry about what happens when they die. The increasingly emphasis on productivity squeezes out the sheltered workshop programs which provided a sense of worth and something to look forward to for many. These programs cost a pittance compared to the money generated and wasted by the causes of the moment.

We have lost our minds in this country. It will, as always, be interesting to read the comments.