A Tender-Hearted God

If God is a true father, does he prefer legalism or love?

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

In some of my recent discussions about religion, I’ve encountered some very interesting perspectives from folks who are Eastern Orthodox. Admittedly, I don’t know much about Orthodoxy at all. It’s not something I’ve ever studied, so I have only the vaguest contours in my mind.

But when a commenter here — recently banned for browbeating everyone else in the discussion and demanding that I answer personal questions in the commbox — made the claim that God only allows a finite number of mortal sins before he strikes us down and sends us to hell, I put out an inquiry on social media to ask where this deeply troubling idea came from.

As it turns out, it’s from St. Alphonsus Liguori, who begins his sermon on the question with the statement, “I intend to show in this discourse that when sins reach a certain number, God pardons no more. Be attentive.”

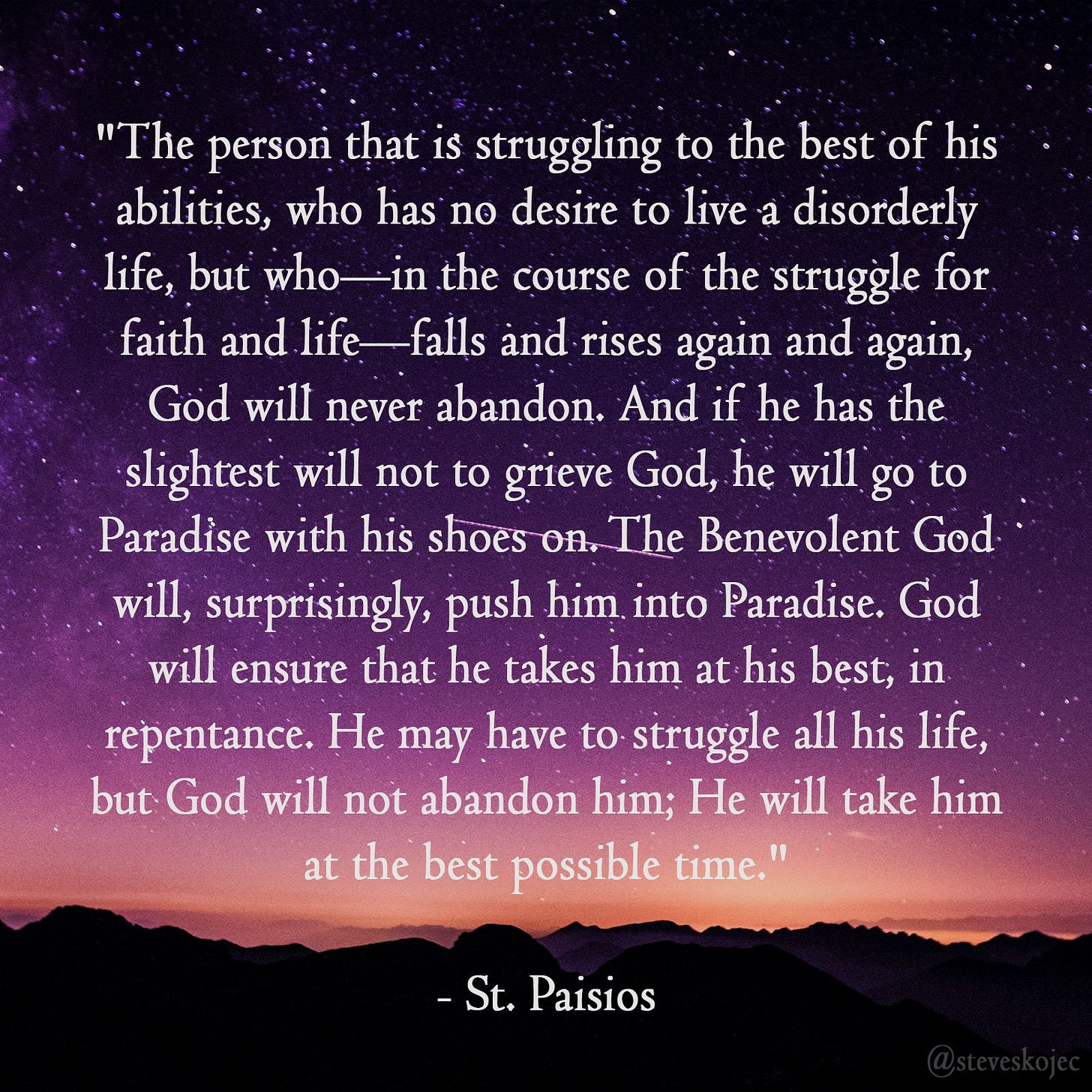

Conversely, an Orthodox acquaintance of mine posted the following quote from one of their saints (not one Catholics share, evidently) that I found…well, absolutely beautiful. So much so, I made it into a graphic for easy sharing:

To my mind, this, and not the fear-inducing view of St. Alphonsus, is the only conception of God that makes sense. At least, it’s the only one that makes sense if we are to believe he is truly a loving father. As a father of eight myself, I’ve come to learn over the years, and even with my children’s varied personalities, that my wrath accomplished little other than to cause my children to live in reflexive fear. Persistence and gentleness, on the other hand, taking time to remind and explain, acknowledge the thoughts and feelings that lead to mistakes, and guide my children back onto the right path, has been much more effective. Not perfect — I’ve got a long way to go as a father, and my kids aren’t little saints — but better than it was when I was a raging beast and everyone walked through the house on eggshells, hoping they wouldn’t be the one to provoke an explosion.

It’s been one of the most important lessons of my life.

And if my earthly fatherhood is in any way an image of God’s fatherhood, then I can only imagine that he, too, sees his children in this way. Far wiser than I, he is not eager to punish and will, even in his frustration, look for every opportunity for his children’s redemption and ultimate good.

My open disagreement with St. Alphonsus, a doctor of the Church, provoked lots of irritable reactions from cranky trads; so, too, did my quotation of the wisdom of St. Paisios. Here’s a tweet that encapsulates both:

The useless factionalism here isn’t new. I used to get the same when I’d post videos from Fr. Seraphim of Mull Monastery. I didn’t care that he was Orthodox, not Catholic. I cared that his talks were the most spiritually nourishing things I’d ever heard, certainly better than anything I’d ever encountered from the pulpit of a Catholic Church.

Aesthetically, I’ve always been a Western Catholic through and through. The Eastern Divine Liturgy, though beautiful in its own way, has never felt like home to me. (I used to go to Byzantine liturgies to escape the tyranny of mediocrity in most dioceses before I found the Latin Mass.) I prefer Catholic art and statuary to Orthodox icons. The heavy ethnic focus in Orthodoxy also makes me feel like an outsider. So I am not proselytizing for Orthodoxy here, or announcing my plan to cross the Bosphorus; ignore those who will almost certainly begin making the assertion this after reading this. I am merely saying that there appears to be a strain of thought in Eastern Christianity that shifts the emphasis away for rigorist legalism and towards divine love and benevolence, and that I find this very consoling. It feels like a salve for a wounded soul.

The same Orthodox Facebook acquaintance who shared the St. Paisios quote with me left a thoughtful, lengthy comment on a recent post of mine, and I thought it worth sharing:

Over the past few days, I've been thinking a lot about your last two articles, both addenda to Against Crippled Religion in their own way.

My struggle with (and eventual abandonment of) my Catholicism occurred on two fronts: experience and understanding, the affective and the intellectual, life and logic, praxis and theory... faith and reason. It's not that one side warred against the other, e.g., the triumph of some mythical "pure reason" over an irrational faith. Both fell out from under me simultaneously.

On the one hand, the side of reason, I stopped finding the claims and arguments plausible. To start, there was the question of Vatican II: was there rupture at or after the council? To believe there was no rupture, that there were no ripples in the fabric of Church teaching, I had to contort my mind and jump through impossible hoops: man both has and lacks religious liberty; the death penalty is both licit and inadmissible; Orthodox and Protestants are both imperfect members of the Church united to us by sacramental grace, and self-condemned heretics and schismatics. I would read the words "development of doctrine" till they lost all meaning, apart from "Don't worry about it."

So if there was rupture? Certainly, I can't believe the Church got it wrong for the better part of two millennia and only just now, as part of the cultural revolution of 1969, awakened to truth? Ergo, traditionalism must be right: we must need to return and hold fast to the "Pian understanding" of the faith.

And that worked for a while. But the more I dug, the more this image of the Church crumbled before my eyes. Whatever details and nuances there might be to this Pain understanding, its foundation is the idea that the pope is supreme and infallible. History reveals how this understanding of the papacy only grew monstrously over centuries. I could no longer, with any intellectual honesty, accept Vatican I's idea that this ultramontanism "was known in every age" and "always". Traditionalism, which wants to preserve the content of 2nd-millennium Catholicism while abandoning the unique authoritative structure that backed it, stopped being rational too. That history had been "de-mythologized" for me.

Over on the side of faith, I was being suffocated existentially by Catholicism. "I'm a good Catholic, and that means I love God and God hates me," quips Kate McKinnon in brogue as contestant on an SNL rendition of an Irish dating show. The ever-present threat of mortal sin hanging over my head as a scholastic Sword of Damocles -- absolute and instantaneous elimination of all charity and grace in the soul, God fleeing from his creation, offended, in disgust. A church with a right liturgy performed rightly, but populated with noxious self-righteousness, embattled anger, fear, and anxiety. A fanatical legalism. "Heavy-handed faith," if you will.

But with all due respect to Aquinas, faith is *not* the intellect's assent to propositions divinely revealed via "supernatural" gift. That's not even at the heart of faith. Faith is something alive, all-encompassing, transformative. It's trust in God and fidelity to him. In the words of my pastor: "Faith is: knowing that you are loved by God," an idea it took me a long time to parse and accept. And if that faith is indeed living, it will manifest itself in love, joy, humility, peace, patience... "fruits," if you will.

No matter how much you may believe or do "the right things" -- be it getting 100% on the Church Teaching True-False test, or saying the words of the Rosary every day at exactly 7pm -- none of that means a thing if it is not transformative.

Without that, why would your kids stay Christian? Either they'd just be too scared to leave, or they grow disgusted with the oppressive fear and hypocrisy. Teach them, yes, but our kids aren't disembodied intellects. Be beacons of love, joy, humility, peace, patience... be a healthy garden, not a toxic one, that they can grow in.

There’s a lot of wisdom in this. We get too hung up on the wrong things, and they can easily become impediments to, or stand in replacement of, an actual relationship with God.

I admit that I struggle with belief. There are lots of reasons for that, not least among them being my as-yet unanswered prayers for authentic faith. I have long since realized that my relationship with God was predicated on fear, not love — a consequence of the Roman emphasis legalism that was amplified even more in the Anglosphere, especially in Irish Catholicism — and that I had come to a point where that was no longer workable. Fear someone long enough, and you’ll find it catalyzing into resentment. It’s pretty hard to love someone you resent. It’s a dangerous thing indeed, then, to make your children primarily afraid of God, to have the idea that his omnipresent gaze is always there, always looking for sins he can count against you, always ready to stand in judgment for your failures. So, too, is the idea that I see repeated almost daily by other Catholics that “we all deserve hell,” which not only stifles belief in our inherent self-worth, but creates a fatalistic resignation to every kind of ecclesiastical abuse.

These ideas also motivate a sort of box-checking Catholicism, an intellectual endeavor where defending doctrine and rote devotion and exposing anything impure become the primary expressions of religious fervor. I compare it to a child who, afraid his father will be angry and punish him, does everything he can to demonstrate his compliance in the hopes that his father’s rage will be held at bay. This can become a very intellectual, theology-driven approach to faith, but it is often very shallow in other ways, not least of them being corporal works of mercy, which are relegated to the “warm and fuzzy” Catholics in the “Church of nice.”

We’ve got heretics to burn, dammit! We don’t have time to feed the poor!

I don’t know if I can re-make my ideas of God; I don’t know if I can come to see him as predominately loving and merciful instead of a God who keeps score — a God who is eager for vengeance against those who offend him. These are hard things to unlearn.

But I appreciate that there is a competing vision of Christianity that wants me to see God in a more positive way. One that doesn’t mind things getting messy on the path to salvation, because human beings are messy and complex, and that teaches that God, who made us, understands this and will respond to every little scrap of our willingness to move closer to him with much larger strides towards us of his own.

This vision of God is not of the kind of father who says, “It serves you right!” when a child falls and hurts himself after breaking the rule about running in the house, or worse, sticks out his foot and trips the child because he’s breaking the rule; he’s the kind who scoops up that child and consoles him first, only then explaining that the rules exist to keep the little one safe.

That’s the kind of father I want to be, so it should come as no surprise that that’s the kind of God I want — no, I need — to believe in. I only hope that’s not naïve.

As someone raised nominally Catholic who spent 30 years as an atheist politely calling herself agnostic, I don't know much about Trads and what they say and do and why. I came back to the Church when I realized the only true alternate to God was nihilism, and nihilism is completely bonkers. I would like to have a community but I probably haven't put in enough effort to find one. Instead, I go to church, read and study online. The intellectual route to faith is tough, at least for me. As hard as it is to say so, one thing that helped me along was a devastating personal loss last year. When you come face to face with death, the rubber of faith hits the road of life in a way that will determine your trajectory, I think, for a long time. In my case, I simply believed. I believed like a small child, in my heart, that I would see my loved one again. I just knew, with a conviction I have never felt before.

There is an argument against the existence of God that runs roughly: God is all loving, and so would grant faith in Him to all who had a sincere desire for such. I sincerely desire to believe in God, yet he has not granted me faith, therefore an all loving God does not exist. I think this argument ultimately fails because while God is omnibenevolent, he is also ineffable. We can certainly say and believe He is all loving, but we can't know exactly what that looks like, because we can't know the mind of God. Whatever God is, He is not an indulgent genie granting infinite wishes as the argument above would have us define Him. Christ, however, has assured us that the Father loves us, so we have it on the best authority.

As to whether God as our Father prefers legalism or love, well, according to John, God is love. The answer would seem to be clear. However, love is not mere indulgence. Love is hard work, and often involves great suffering. It requires faithfulness, honesty and determination. Love is hard. God has given us an instruction manual on how to live and love, and sent his own Son as an example. We, as fallen sinful human beings, are not capable of following such an example, of course, we are only asked to try. God does not expect us to do the impossible.

There are many saints and they have said many things over the last 2000 or so years, but the teaching authority of the Magisterium has laid out the Catholic faith for all to see in the Catechism. What I do not find there is any reference to the number of sins one can commit before God will strike one down or send one to hell. Nor do I see that there are limits to God's mercy. I see rather that no one is to be deemed irredeemable by us. Still, we know that God abhors sin and so obviously we should strive not to sin, and when we do sin we ought to repent. One wonderful thing about being Catholic is that we believe in the forgiveness of sins.

I don't think you necessarily need to look outside Catholicism for examples of views that differ from the apparent bean counting legalism of St. Alphonsus. Jacques Phillippe, for example has written some lovely little books on finding peace and the path to holiness for Catholics. In "Searching for and Maintaining Peace", he recounts how St. Therese of Lisieux encouraged one of her sisters by telling her that, in the experience of a great exorcist, demons themselves could never overcome the "bloody little dog" of goodwill. Goodwill being just the unfailing desire to please God and getting back up every time you fall into transgression. We can begin again, and again, and again. Every day, every hour, every minute. God knows how imperfect we are and loves us anyway.

May God bless you and grant you the peace beyond all understanding.

Thanks for this article. I can relate to what you wrote about in so many ways. I am subscribing because you are not a ministry and you are not profiting from stirring up fear and division in the name of righteousness. Good luck in this business venture!