A Visit to Cottonwood Ranch

Old friends and new problems. Gratitude in the midst of trial.

This is a free post made possible by paid subscribers.

Writing is my profession and calling. If you find value in my work, please consider becoming a subscriber to support it.

Already subscribed but want to lend additional patronage? Prefer not to subscribe, but want to offer one-time support? You can leave a tip to keep this project going by clicking the link of your choice: (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe)

Thank you for reading, and for your support!

The first time I actually got to know Paul, it was from the passenger seat of his beat up, late-80s, beige Datsun pickup truck, on a road trip from Dallas to New York. Our friendship was forged in the mutual decision to travel 1500 miles to see Pope John Paul II, 30 years ago this month.

We were 17.

Paul and I were classmates, both of us out-of-state seniors at The Highlands School in Irving, Texas — a school run by the Legionaries of Christ. Paul was from Idaho, and lived with a local family. I was from New York, and lived in the part of the school building that had formerly housed boarders from Mexico who attended a separate academy that had closed down that fall. Technically, I lived with the priests and seminarians who ran the place. We ate our meals together and shared a chapel, but the religious lived on the third floor, and I lived on the nearly-empty second level, along with a couple of young laymen who were not students, but were working as volunteers with the Legion.

One of the reasons it took me so long to make friends with Paul was that I had recently made a new best friend — Hugh — who I wrote about in Dallas, 1995:

When I arrived at the school, the place where I’d be helping to lead a summer camp for rich young Mexican heirs, I was introduced to a young man my age at the bottom of the stairwell heading up to my room. He stood sweating in a red soccer shirt and backwards baseball hat, having been working the school grounds with the landscaping crew for his summer job. He was the nephew of my priest-friend, and while I was anxious to check out where I would be staying, in just a few minutes of conversation, we hit it off like we’d known each other our whole lives.

The next day, on the way to Fort Worth for a day of Texas-themed sightseeing, we sat in the back seat of a car mapping out the Venn diagram of our respective interests and finishing each other’s movie quotes as his mom and her priest-brother chatted quietly up front, throwing approving glances back every now and then.

Later that afternoon, I realized with a shock as I walked the old stockyards, laughing with my new acquaintance over rough-hewn crates of penny candies, that I was 17 and had never really had a friend before. Someone who got me and shared my interests, sense of humor, and enthusiasm.

And now I did. This was just something qualitatively different than anything I’d experienced in nearly a dozen years of public school.

Paul and Hugh were already friends, having spent their junior year together. But whereas Hugh seemed like a long-lost brother I’d never met, Paul was a bit more of an enigma to me. A solid Idaho farmboy of good German stock, he was a relatively quiet, unflappable guy with a soul-deep independent streak. In addition to the dusty old Datsun, he had a fancier ride: a Honda CBR 1000 that topped out at about 180mph. (To my knowledge, he never pushed it past 160, and that only when he — allegedly —may have had to outrun the cops the cops that one time.)

That October, just two months after school started, Paul decided he was going to New York City to see the pope. He didn’t much care what anyone had to say about that, least of all the school administration. When he asked if anyone wanted to go with him, everyone else was either uninterested or noncommittal. I was away from home for the first time, and a month away from turning 18. I thought about it for a few seconds, and realized the only other person who didn’t need to ask permission and didn’t care what anyone thought was me.

“I’ll go,” I said.

We made our plans. We informed the powers that be that we would be skipping classes for about a week. They didn’t like the idea. We told them they should like it, since it was such a committed Catholic school, and we were going to see the pope. They relented, if reluctantly, and before long we were on the road.

It was an incredible trip. It was not the first time I’d driven a stick shift, but it was the first time I got it almost right. We listened to a ton of good music. We talked about our lives. We shared the adventure of driving across the country — a first for me. I’d never driven anywhere outside the Northeastern United States. It made me a roadtripper for life.

We made it to Central Park just in time for the Papal Mass, and only at that moment did we realize we were never going to get in. We didn’t have tickets — hadn’t thought of that at all. The downside of impulsive decisions made with good intentions but no real plan. So instead, we spent the day sightseeing in Manhattan, and left on a route that took us through Harlem at night on the very same week the OJ Simpson “not guilty” verdict came out. A couple of white-as-snow high school boys in a rough part of the city where the festivities had taken to the streets. Paul had taken certain safety precautions I won’t commit to writing here, but when we got pulled over in Maryland a few hours later after the fuel filter went out and we were going well under the speed limit, I was relieved to find that when the trooper asked him to remove the pillow that was covering his lap, there was no longer anything hidden beneath. We spent that rainy night with my great uncle — also named Paul — at his house just outside of Washington, DC.

On the way back, we made one particular stop that would turn out to be eerily predictive.

We visited Nate, a student at Christendom College at the time, a child of the family Paul was living with in Dallas. Nate had graduated from The Highlands the previous year. I had never met Nate before, but we hit it off right away. What didn’t jive with me was the vibe at Christendom. A tiny little school in the middle of nowhere Virginia, where the students had to wear uniforms, and the rigid segregation between the sexes seemed pretty obnoxious to almost-18-year-old, girl-crazy me. Paul and I drove away from there in agreement that we would never want to go to a school like that. We didn’t even like the area. It was beautiful, but there was nothing there.

What we couldn’t have known at the time is that about a decade later, Paul would move with his wife and children into a house that was right across the street from Christendom, where he would build the foundation for the rest of his life. His future home where he would raise his children and run his businesses was there the whole time.

When I got back to The Highlands, I had two best friends.

Paul and Hugh and I would go on to attend Franciscan University of Steubenville together, along with a whole bunch of other people we knew through our time with the Legion. In college, Paul would meet his future wife, a young woman named Kristen with fiery red hair who grew up in a nearby area of Virginia to where he would eventually settle down.

Life is funny in ways we rarely expect.

Paul and I had many more adventures together over the years, including the biggest road trip we ever took — from Steubenville Ohio to Mexico City for the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe in 1998, and all the way back up Mexico’s West Coast, through Arizona, to Denver and beyond. By the time I got back to New York at the end of that trip, hitching a ride with a couple of my cousin’s stoner buddies in Boulder who were heading home for Christmas in an old Volvo with a broken heater through the middle of an absolutely brutal midwestern winter, I’d traveled 11,000 miles by car in just two weeks.

I spent the summer before Steubenville living in Idaho with Paul and his family, including his late father, Chuck, where I worked in the family well pump business and did my best to help out on the farm. Paul always had cows back at home on the family land, and he’d sell one whenever he needed money while away at school.

Later, Paul would go on to own a pretty impressive herd of cattle that grazed the rolling green hills of Front Royal, Virginia. And he started not just one but two beef companies — Primal Beef, which ships high-quality meat all over America, and Cottonwood Ranch, the local farm-to-table beef business named after the little town he grew up on the Camas Prairie in north-central Idaho.

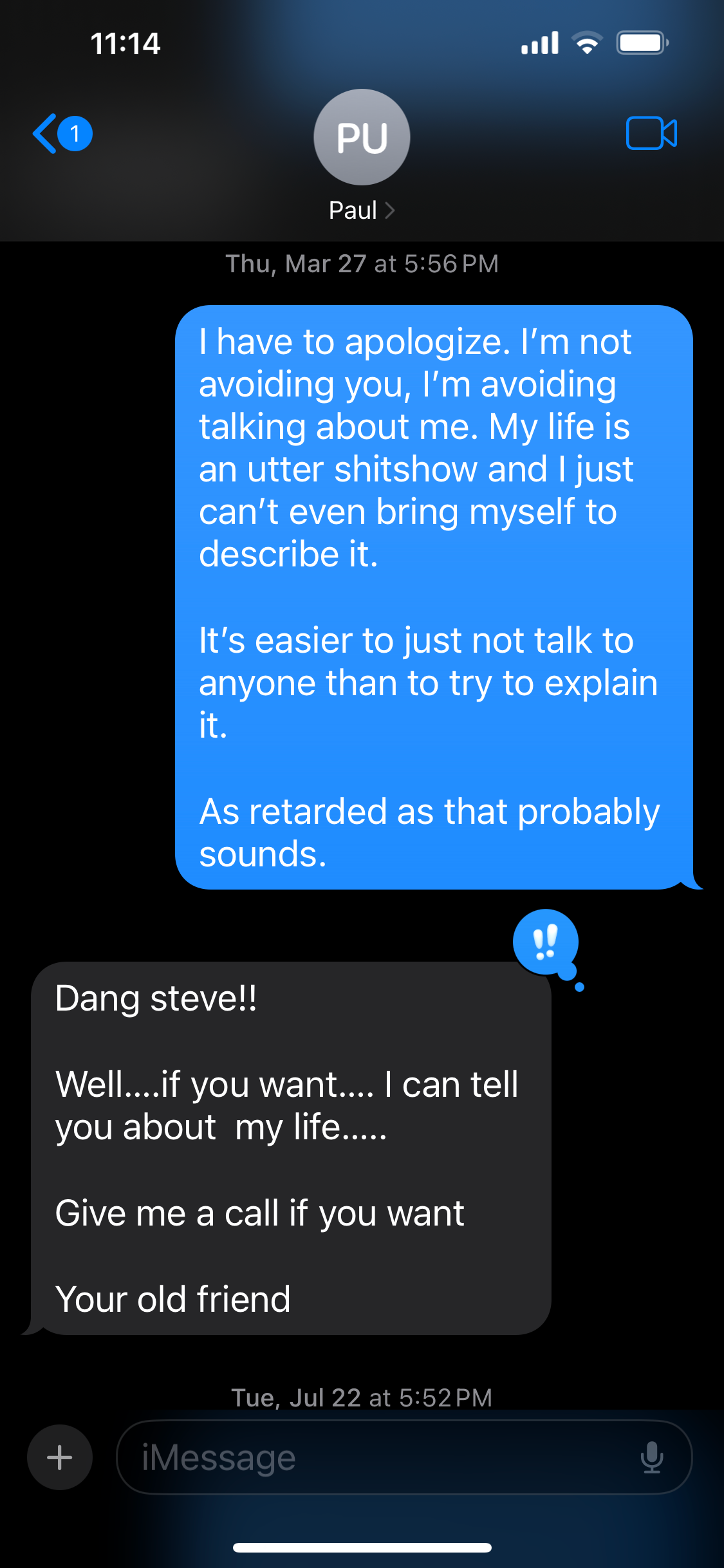

When Paul called me last Wednesday, on my first full day away from home, I was still asleep. I’d been dodging his calls for months. At one point, earlier this year, I texted him in an attempt to excuse my avoidant behavior

I checked my voicemail. He had heard that I’d left home, and he was concerned. I decided I needed to knock off the bullshit and be straight with my old friend. We’d been out of regular contact the past few years, but Paul is one of those guys you can not see for half a decade and then just pick up right where you left off. More than ever, I needed to be around the people who knew me best.

I picked up the phone.

It was a brief conversation, but his compassion was so genuine. He’s a real-world guy who doesn’t spend much time online, but Hugh — who now lives just down the road from Paul in Front Royal — had told him about my separation. He asked if there was anything he could do.

“Actually,” I said, “I’m driving north from the Carolina coast right now, and I’ll be in Virginia tonight. Would it be OK if I crash with you tonight?”

“Yeah, of course!” he replied. “Come on up! I’ll have steaks and bourbon for you when you get here.”

I pulled into Front Royal just as twilight turned to darkness in the wake of a gorgeous sunset. I stopped for gas and tried to shrug off the surreal familiarity of the place. I hadn’t been there in years, but I’d been there countless times, and know a lot of people in that town. Friends. Family. My folks actually live there somewhere, but we haven’t been on visiting terms much in recent years. I was apprehensive. I had no idea how to even talk about what I was going through.

I drove in silence, winding my way down the aptly-named Dismal Hollow Road in near-total darkness, trying to steel myself against the discomfort of talking about a life that had come apart at the seams. When I arrived at the old yellow farmhouse, it looked the same as it always had. The surrounding property had been built up over the years since he’d bought the place. He had two huge barns, a guesthouse that used to be a garage, and a huge pasture out back. Still, place felt exactly as I remembered it. It was weirdly quiet. I was used to visiting when they were having big get togethers, but that night, there was not a soul in sight.

I walked up the steps to the front porch, and knocked on the door. After a few seconds, I saw someone moving within, and when the door opened, I was surprised to see not Paul, but Hugh, bearded and burly. He didn’t say anything, just wrapped me in a huge bear hug. I can’t even type the words without tears filling my eyes. It felt so good to be welcomed and wanted. To know that for that night, at least, I was safe with people I could trust.

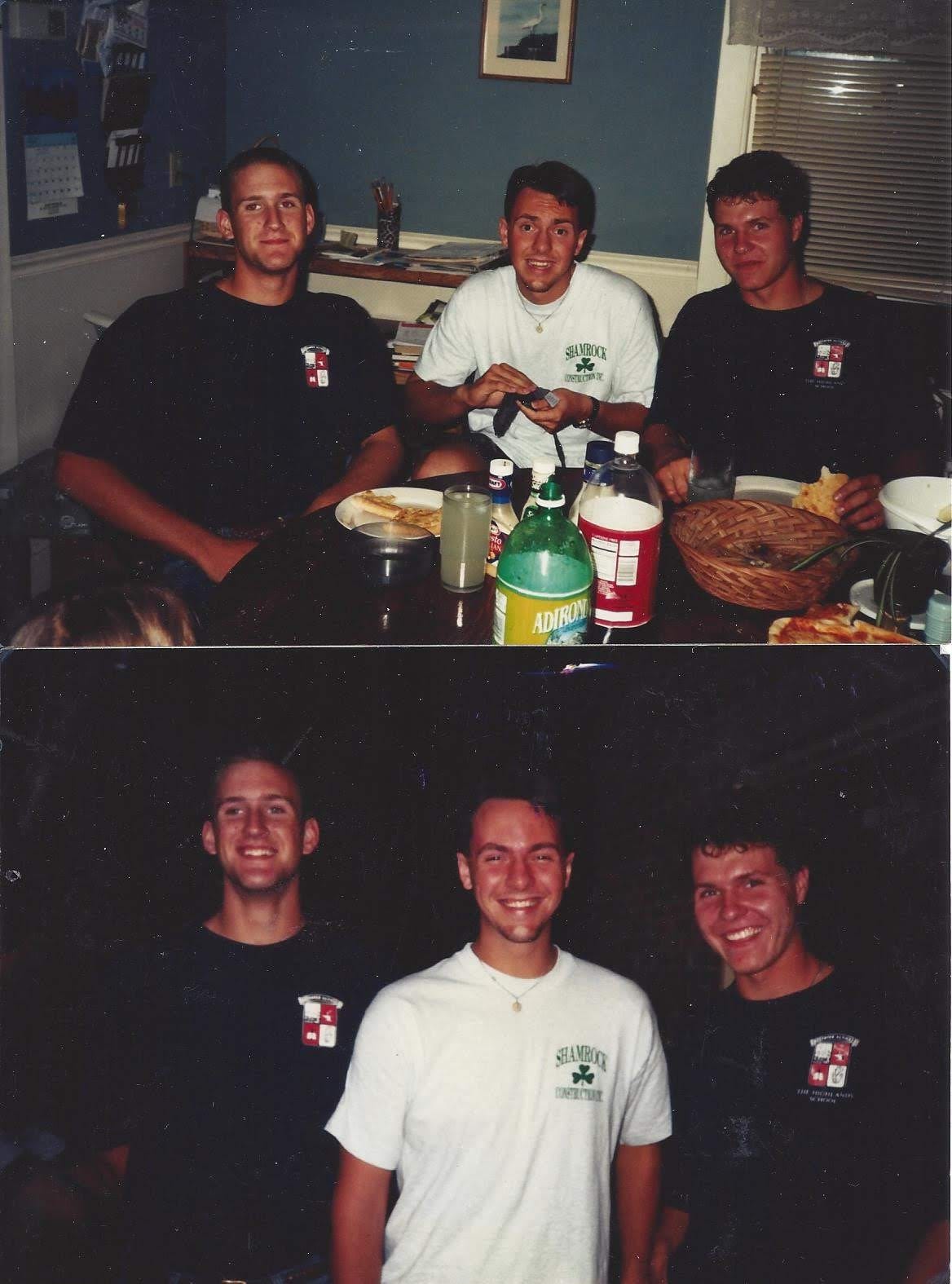

I don’t know how it works, the things where old best friends can have many years of experiences that set them on separate paths, only to get together and have the same dynamic re-emerge. 30 years of friendship, even if it includes large stretches of time apart, is no small thing. We were still the same three guys who stood on my front porch in Kirkwood, New York, in 1996, huge grins on our faces, getting ready to go volunteer for a year with the Legion, and experience everything that came with that. Later, we would all decide, each for his own reasons, to leave the cult behind.

We marveled at the fact that the photo of the three of us below — the last one anyone had taken of the three of us together — was already a decade old:

When the Legion turned on me after I left, and started an active campaign to ruin my reputation with all the friends I’d made through my involvement with them, these were two of the guys who stood up for me, no matter what it cost them. They have always had my back, and even now, that still holds true.

They put me at ease. They didn’t force me to talk about anything I wasn’t ready to discuss. Paul threw some steaks on the Traeger, and Hugh busted out a bottle of bourbon. We drank. We smoked. We ate. We caught up. We talked until 3AM.

I learned about the trials and triumphs of Paul’s handful of businesses. I learned about the new gourmet ice delivery company Hugh had started after being laid off from his long-term corporate gig last year, and how they were about to quadruple their business. Two of us had kids who are already married. Hugh told me his son, who I haven’t seen since he was about 10, was on the cusp of growing taller than he is — and he and I are both 6’4”.

After a few drinks, I finally opened up. They listened, asked questions, and told me stories about people in their own lives who had or were still going through similar things. More people than I would have guessed. Some of them people I also knew. Heartbreaking stories. Stories of loss even greater than my own.

When sleep could finally no longer be put off, I drifted off on the bottom bunk in a spare room, and didn’t wake until the sun was well into the sky.

That morning, Paul gave me a tour me his empire. He walked me through each of the buildings, then took me to a spot where we could overlook the back 40 acres, where he kept his cows. Then he took me into town and showed me their family’s latest venture, a new farm store, which was picture perfect:

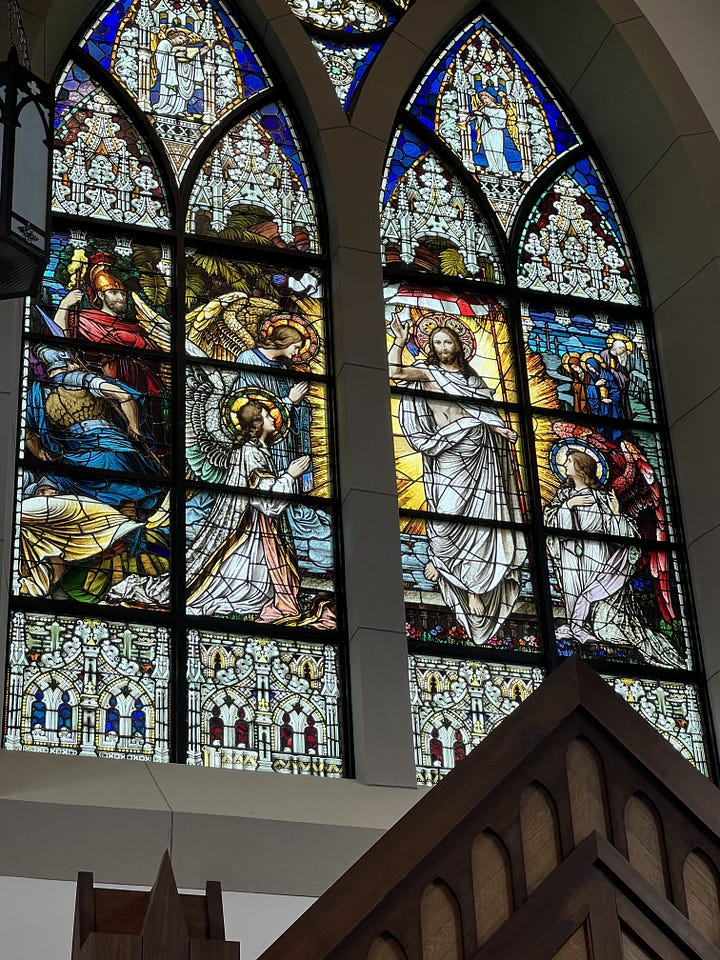

Paul and I had a late breakfast at a local diner. We stopped to see the new Christendom College chapel on the way back. I hadn’t been inside a church in a while, but a lifetime of habit and familiarity rose up in me. The sign of the cross with holy water. The genuflections as we passed the tabernacle. The reverent lowering of our voices. A small, skeptical voice in my head questioned going through these motions, but I silenced it with a reminder that there was no reason not to show the same respect I always had.

At the end of the tour, I felt compelled to ask for a moment, and I knelt in one of the front pews to say a fervent prayer for my family. The fear that no one was listening couldn’t drown out the desire for it to be so.

Finally, we headed back to the farmhouse, where we sat on the front porch and stared out past a weathered American flag and a lonely old tire swing at the lush green landscape under a canopy of clouds.

Paul smoked a cigarette and I popped in a coffee-flavored nicotine pouch, and we talked more about the situations and experiences of not just myself, but others we knew, who are struggling in marriages that have either ended or are actively falling apart — all of them amongst people who at least once believed in the indissolubility of such a covenant.

At one point in our conversation, Paul explained his own approach to faith. It’s not my story to tell, but he focused on the idea of simplicity.

Understand that Paul was the valedictorian of our high school class. He’s an incredibly intelligent man who really thinks things through, and has deep insights about many things.

But explained to me that he believed that if he approached things the way I do, if he tried to make sense out of the suffering he sees in the lives of people he loves who have tried to live their lives the right way, it would drive him crazy. He told me that when his kids come home from college and sit around the table debating theology, he enjoys it, but feels no need to join in. To him, what matters is to believe, to prioritize the things that are most important — his responsibilities as a provider and his family — and to leave the rest up to God.

I found myself wondering why I have to question everything. Why I so desperately need things to make some damn kind of sense. I found his explanation to be a nearly-perfect encapsulation of the childlike faith Christ commended his followers to adopt…and yet, and yet, I knew even as I tried to cement this concept in my own mind as a better way that it was something I could never do. Or at least, something I could not do anytime soon. My search for meaning amidst the suffering is far from its conclusion. And yet it still felt like an important piece of the puzzle I’m trying to assemble along this pilgrimage towards whatever comes next.

Maybe someday, if God decides to answer my prayer and give me real faith, a time will come when I can live that way. I already know that any return to the faith, if it should come, will carry the temptation to return to old habits: theological debates and prooftexting documents and making the perfect the enemy of the good.

But I also know that this is no real way to live. The mysteries I find so hard to accept are surely part of the deal. And if I really do want to ever believe again, accepting that I can only know what I can know and leave the rest as open questions will be the only way I’ll likely survive the tension between skepticism and belief. It seems an odd thing to believe that something is more true than any other thing, but also to understand that to look at it too closely and try to square its many circles is a path to madness and disbelief. I am already in the latter state. Is the former state achievable for a man like me?

After hours of conversation, we said our goodbyes as he loaded me up with beef jerky and some premium beef hot dogs I’ve been eating ever since. We didn’t solve anything. Didn’t even come close. But there is no vanity in making the attempt.

I drove off that afternoon a richer man than I’d arrived.

He doesn’t need my approval, but I’m so proud of my old friend and all that he’s accomplished. I’m proud of Hugh for creating a whole new business in the wake of his own loss of a career. I’m impressed with the life they’ve built for their families — a life of permanence and stability and community in a tumultuous world.

I’m proud to call these men my friends after all these years, and everything life has thrown at us. I’m so grateful that I was finally able to overcome my shame, my feeling of failure, and let them be exactly the kind of brothers I needed in the middle of my darkest hour.

And I hope that if the unfortunate moment ever arises, I can do the same for them.

If you liked this essay, please consider subscribing—or send a tip (Venmo/Paypal/Stripe) to support this and future pieces like it.

Steve

I soaked this post up like a sponge. I loved every single line, seeing it all in my minds eye.

Paul's focus on the aspect of simplicity is spot on. It comes down to that...after all is said and done for us all, living lives of suffering along side of you as every reader does, we will all eventually come to see things through Paul's eyes and be better for it.

Less is more and simplicity is the best of all. Peace is to be found there.

Steve I’ve just subscribed out of thanks for that photo of the Resurrection Window at Christendom College. That was removed from my now closed Parish Sacred Heart of Wilkes-Barre PA. Seeing it now is like discovering a long lost photo of a beloved relative. Thank You!!! And May God grant you peace in the days ahead.