Pseudo-Chesterton on Morality Without God

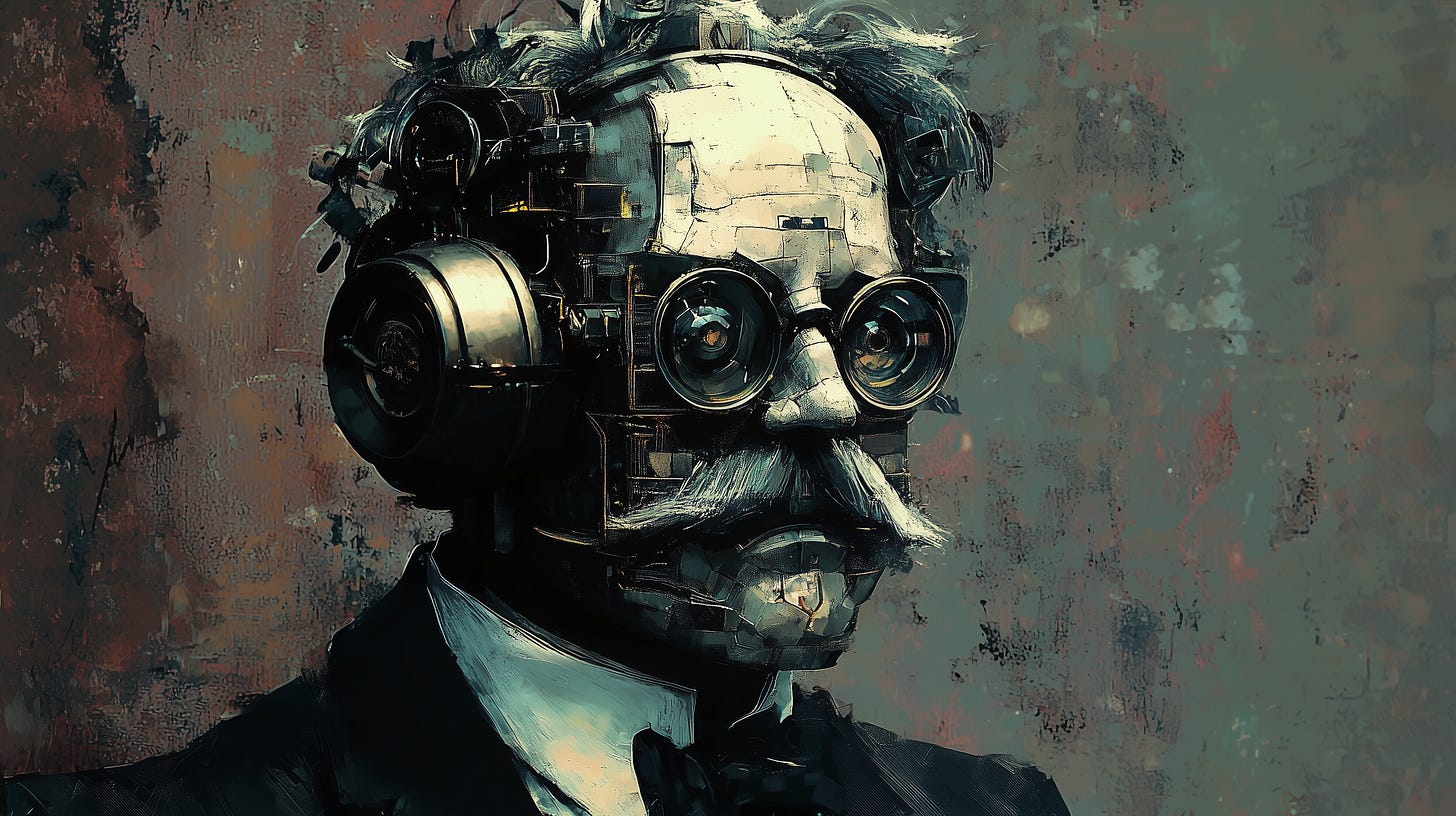

An AI Impersonating Chesterton Makes a Case to Convince the Skeptic

The following is a free post. If you want access to our comment box & community, subscribers-only posts, and future subscribers-only features, you can grab all of that for just $8 a month (or even less on an annual plan) by subscribing right here:

Writing is how I make my living, so if you like what you see here, please support my work by subscribing!

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy me a coffee to help keep me fueled up for writing, you can do that here:

In the comment section of my essay on being spiritually homeless with or without religion, Chuck Fox offered the following AI emulation of G.K. Chesterton making a case for the existence of morality without God.

It’s a decent enough impression of old Gilbert Keith, without being too on the nose, but what really impressed me was the argumentation itself. I’ve touched on this question in essays like “If God is Not, Is Everything Permissible?” What our Artificial Chesterton says here is, essentially, what I’ve come to believe on this topic, but it is articulated better than anything I’ve been able to piece together.

I would also say here that the following in no way precludes or diminishes the idea of God’s existence, it only takes aim at the false belief that a coherent godless morality cannot exist. We do a kind of violence to ourselves in failing to acknowledge that we are more than just depraved and craven beings absent the machinations of grace. Put another way: the Protestant notion of Total Depravity gives us terribly short shrift.

In any event, without further ado, I’ll let Pseudo-Chesterton make his case, with my thanks to Chuck for bringing this to my attention. I’d have hated for this to be lost in the comment section when it’s worthy of being shared widely.

The Foundation of Morality Without God

It is a strange and thrilling thing to argue for the possibility of morality without God, as if one were advocating for a roof without walls or a symphony played upon silence. Yet it is precisely such a task that we undertake here—not because the existence of God is unimportant, but because the skeptics among us demand to see whether morality can stand even if the divine scaffolding is removed. And I, for one, am inclined to believe that it can—but only because the architecture of humanity itself is sturdy enough to bear the weight.

The Common House of Humanity

Let us begin with something simple and sane, something that even the most quarrelsome relativist cannot deny: human beings are profoundly social creatures. Our very survival depends upon trust, upon the idea that I may entrust my life, my labor, and even my frailties to the hands of another without fear of betrayal. Without trust, there can be no society; without society, no civilization; without civilization, no life worth living.

Thus, the first bricks in the house of morality are laid not by God’s decree but by the very nature of human existence. The protection of the vulnerable, the keeping of promises, the insistence upon justice—these are not abstractions, but necessities. A society that abandons its weakest members, that treats promises as trifles, or that permits might to make right will not long endure. History is littered with the ruins of such societies, and their fall was not a matter of divine wrath but of human consequence.

The Golden Rule and the Bedrock of Trust

Now, a clever skeptic might say, "Ah, but morality is just your opinion!" And this is where I must pause to laugh, for morality is nothing of the sort. The great genius of morality is not that it is my opinion or yours but that it reflects a common instinct—the instinct to see ourselves in others and to act accordingly. Call it the Golden Rule, call it empathy, call it enlightened self-interest if you like, but its truth is evident to anyone with eyes to see.

Take, for example, the matter of fidelity. Why is it wrong to betray one’s partner, even if they never find out? Not because of some celestial decree but because trust, once broken, weakens the bonds that hold people together. A society that normalizes infidelity would not merely harm individual relationships—it would sow suspicion and cynicism throughout the whole fabric of life. And while I may not need a commandment to tell me this, I do need a conscience that whispers, "Would you wish this done to you?" The answer, invariably, is no.

The Pragmatic and the Eternal

But here we come to the crux of the matter: is morality, then, merely pragmatic? Does it serve only to ensure that society does not collapse under the weight of its own selfishness? To this, I must answer both yes and no. Yes, morality is practical; indeed, it is the most practical thing in the world. But no, it is not merely practical, for it is also beautiful, and beauty is never "mere."

Consider the example of protecting the unborn child, who is surely among the most vulnerable of all. Some might argue that the child’s dependence makes it expendable. But this is precisely why the child must be protected: because the measure of a society is not its strength but its willingness to care for those who cannot care for themselves. To abandon the unborn, or the disabled, or the aged, is to deny the very principle that makes morality possible: the recognition of value beyond utility, of dignity beyond power.

The Rebuttal to Relativism

Ah, but the relativist will object: "All this is just human opinion dressed up in fancy rhetoric!" To which I reply: Of course morality is human, for it is humans who need it. But to say that morality is human is not to say that it is arbitrary. The need for trust, the value of empathy, the principle of reciprocity—these are not inventions but discoveries, as real and objective as the laws of gravity or the truths of arithmetic. They are the bedrock upon which any society must be built, whether that society invokes the divine or not.

A Conservative Foundation

In this sense, morality without God has a curious kinship with morally conservative principles. It insists upon the protection of life, the honoring of commitments, and the fostering of a culture that values trust and dignity. It understands that morality is not a series of rules imposed from without but a living tradition arising from within—a tradition that must be preserved, not because it is sacred but because it is true.

The Conclusion of the Matter

And so we return to the beginning. Can morality exist without God? Yes, it can, for it is rooted in the nature of humanity itself. But I will leave you with this paradox, for paradoxes are the soul of truth: while morality may not require God, it requires something very much like Him—a recognition that beyond our fleeting desires lies a deeper order, a shared responsibility, and a truth that binds us together. Whether we call this God or nature or reason, it is the foundation of the moral life, and it stands firm.

And that, I think, is something even the skeptic can believe.

Wow, I’m glad you shared this because I missed it in the comments. Very impressive.

Thanks for sharing this. It's very good and does have a definite "Chesterton sound."