The Technology We've Made Is Now Remaking Us

The following is a TSF free post. If you want access to our comment box & community, subscribers-only posts, The Friday Roundup, and the full post archives including this one, you can grab all of that for just $5 a month (or even less on an annual plan) by subscribing right here:

Writing is how I make my living, so if you like what you see here, please support my work by subscribing!

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy me a coffee to help keep me fueled up for writing, you can do that here:

The first time I ever went to a Byzantine liturgy, I was conscripted to serve at the altar. The year was 1998. I had traveled to Michigan with college friends for Easter break during my Freshman year at Steubenville. And suddenly I had found myself in a blood-red alb, dragged into the sanctuary, and told to just follow along. My friends — two brothers from a family of 13 — were also serving. Except they knew what they were doing and I was completely lost.

I was mortified.

I had been an altar boy for many years at my home parish, but it was a Catholic parish in northern Pennsylvania that was about as standard-issue as a post-conciliar rural church full of half-converts from Protestantism as you can get. (I say half-converts because many of them retained their Protestant sensibilities and even some theology, which is only possible in a parish of this kind, where such boundaries are often quite blurry.)

At that point in my life, I’d only ever been to one Traditional Latin Mass, and I hated it. I was wholly unaccustomed to mystery on the altar. Everything was so transparent and overly explained it may as well have been a YouTube DIY video about how to unclog a toilet…if YouTube had existed at the time.

The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, on the other hand, was positively opaque. It was filled with ancient ritual and symbol and music that came in great ebbs and flows but never stopped. For the first time, I was on the other side of an iconostasis — metaphorically peeking behind the veil. And the Church was absolutely full of imagery in a way I had never seen.

It’s been over 25 years since that Easter, and my memory isn’t what it used to be, but based on the photos, I believe the parish was St. Michael’s in Flushing. I grabbed these image from their unofficial Facebook page, to give you an idea of the absolute feast for the eyes contained within:

This was my first taste of a traditional liturgy, and it was a lot to take in.

My friends told me that although they were canonically Roman rite, their parents had taken refuge at the Byzantine parish after the Second Vatican Council, when Catholicism in the Detroit diocese took a significant turn for the worse. And what their pastor had explained to them about the artwork was that it was a kind of visual catechesis, the stories of the Gospels covering every inch of the walls in a way that could teach even those who could not read. Going to liturgy every Sunday meant repeated exposure to these scenes, which, over time, created a sort of visual tapestry in the mind of the stories undergirding their faith.

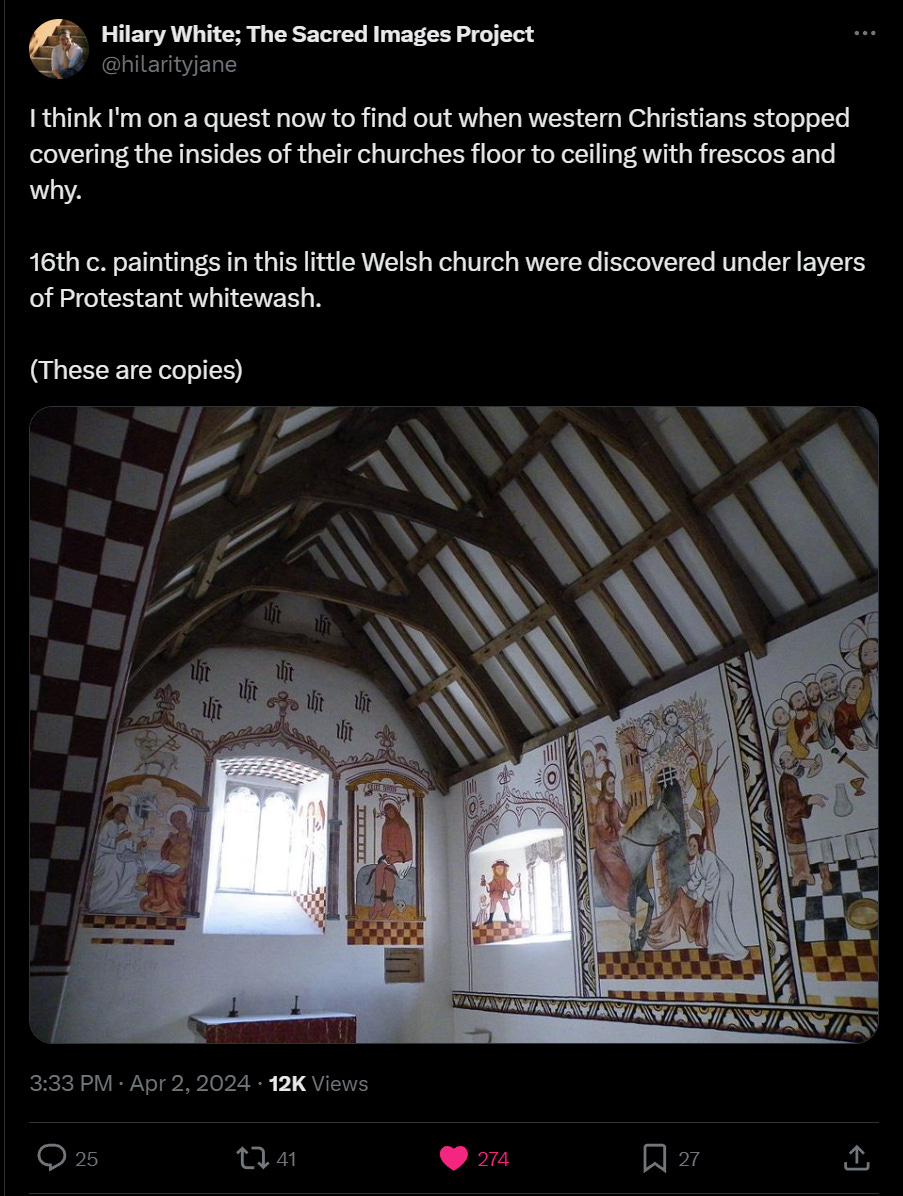

I was reminded of this today when I saw my friend Hilary White post the following:

For those who don’t know, Hilary is an Anglo who has been living in Italy for the past couple of decades. She has switched careers from journalism to sacred artist and has begun traveling to document the many historical Christian treasures available to her there.

I replied to Hilary, thinking of that Byzantine parish in Flushing:

I love this pursuit. Utterly removed from polemics. Just a question about why we forgot that sacred art is pedagogy.

My hypothesis: it changed with the increase of literacy. The old churches were picture books of catechesis for people who couldn’t follow along with the liturgy or read books about their faith. They learned by letting their eyes wander. Once reading became a thing and liturgy could be better understood, the need went away, and the style was probably seen as busy and kind of primitive. A mistake, surely, but an understandable one.

Literacy, it should be noted, is itself a technology, when we consider that technology is defined as “the practical application of knowledge especially in a particular area.”

There are surely other explanations than “people learned to read” for why religious art in churches changed so drastically, and I don’t wish to oversimplify. But my theme for this post is not so much about the question she’s asking as something bigger, that has been on my mind for several years now:

What effect has the rapid development of technology (especially information-related tech) and mass literacy over the past couple of centuries had on the human race? How has it changed the way we perceive the world? How has it altered our epistemology? Can modern man ever really understand how different our context is from the one experienced by our forebears a hundred or more years before? And can we truly grasp the way our use of technology is shaping us?

Kale Zelden and I have an ongoing debate about tech. I say it’s neutral, and that any negative outputs are a result of what we bring to it when we use it. A hammer can be a tool for building or a murder weapon; it’s the human user who determines the moral outcome of its use.

Kale disagrees. He argues that it’s absolutely not neutral.

Further, he says in response to my objection:

My rejoinder:

I should pause here for a moment to explain what I mean by “the algorithm shapes us.”

In another discussion, earlier this week, myself and several other very online folks were talking about the euphemism that have arisen recently to avoid saying that a person has died. Some were lamenting the use of “passed,” while others say they’ve heard that for their whole lives stretching back decades. Others said that many don’t talk about even passing, but do a “celebration of life.” I remarked that I have been hearing young people use the term “unalived” on social media, with sufficient frequency that it must be a semantic trend. Which is when I got a most interesting reply:

I honestly hadn’t considered that this was the reason, but it made sense. But what made even more sense, suddenly and somewhat terrifyingly, is that we have allowed our technology to become such a force that we are now in direct competition with it. We know this when it comes to AI, and the human jobs it is already beginning to replace. But as we live more and more online — the majority of the most thought-provoking discussions I have take place there — we become increasingly dependent on remaining in good standing with the platforms where we share our opinions. If we run afoul of some algorithmically-enforced rule and find ourselves banned, there’s rarely any human recourse. I appealed my Twitter suspension for over six months before I got it overturned, losing countless opportunities and missing out on early rounds of advertising revenue share for something that the bot army behind the decision finally deemed a “mistake.” I was not offered a refund on my premium subscription, and there is no way to count the missed opportunities for grown that resulted in my inability to share the content I make for a living with the audience of over 14,000 people that I painstakingly built over 15 years.

We say it often: “Twitter is not real life.” Except that it actually kind of is. Real friendships are made there — I wouldn’t know Kale if it weren’t for Twitter, and we’ve created an in-real-life friendship where we’ve been to each other’s homes and met each other’s families because of it. Twitter drives a not insignificant portion of traffic to this Substack, where at least some of it converts into paying subscribers. (As does Facebook, etc.) If you sell opinions online, you actually need social media to build an audience. There is no substitute.

So you find yourself engaging in little acts of self-sabotage and censorship in the hopes of avoiding the notice of the panopticon of the algorithm and its programmed-in biases.

And over time, that changes the way you think and speak and act. Culture is downstream from that.

The thing is, we don’t have any precedent for this. Human history has no analogous example. There has never been a time in the entire history of the world before about 30 years ago where everyone, everywhere, could interact with each other’s ideas and knowledge, without ever leaving home. There is a kind of weird intermingling of forces in play, and it’s absolutely spilling out into the real world. Just look at the loss of faith in experts and institutions post-COVID. That happened almost entirely online, but it now influences in-person interactions and consumer decisions every day, and will have an electoral impact for years to come.

I first started thinking about this when I was covering the Vatican. It became increasingly clear to me that they had no idea how to handle the fact that they no longer controlled the narrative. My friends in Rome — Hilary being one of them — remarked early in the Bergoglian Papacy that they didn’t know they were no longer in charge of “the truth” and could not expect people to just sit there and buy the lies anymore. We could look things up. We could compare past statements to new ones. We could catch them in the deceptions in real time. And despite being keyboard warriors in far flung places operating out of spare bedrooms on laptops and home-built PCs, we were bringing an outsized influence to the discussion of Church politics.

It was a kind of asymmetrical warfare for which they were entirely unprepared.

But it also got me thinking about the stories Catholics tell themselves about the Church and its supposed consistency of thought and inviolability of teaching. As I watched Francis reveal himself to be a heretic over and over again, I found myself growing increasingly incredulous of the claim (which I myself had made until I started waking up) that this was an entirely unprecedented situation.

But was it?

Pope John XII was notorious for raping female pilgrims to the Vatican and was murdered in the bed of a lover by her husband. Pope Alexander VI was reported to have held a banquet-turned-orgy with 50 prostitutes, wherein prizes were given to those attendees who could “perform the act most often with the courtesans.” Pope Urban VI was said to have complained when the cardinals who conspired against him didn’t scream enough while being tortured. And Pope Stephen VI famously had his late predecessor, Pope Formusus, exhumed, his corpse placed on trial, and his dead body mutilated and thrown into the Tiber.

I felt like a fool. Was I really supposed to believe that even the worst popes of history were, by some machination of the Holy Spirit, theologically orthodox while performing such heinous deeds?

Or was it more likely the case that the heresies of previous popes were hidden from history by the most powerful and influential institution in the history of Western Civilization, which had a narrative of divinely-granted infallibility to maintain?

During my 7 years covering the goings on in Rome, I became increasingly convinced that the only difference now was that the Vatican could no longer keep its scandals contained because it lacked the power to shut down inconvenient narratives. The same Church that could force Galileo to spend his remaining years under house arrest for using science to contest an erroneous biblical cosmology could not stop a blogger in the United States from telling millions of people what they were really up to. A story I published received a direct response from a pope emeritus in an official Vatican statement - me, a guy writing on a Wordpress site he put together for 50 bucks while working from his windowless basement in Manassas, Virginia.

The rules have changed.

What I saw happening to the Vatican is now what’s happening on everything from vaccine skepticism to electoral fraud conspiracism to UAP disclosure advocacy to the questions surrounding whether Jeffrey Epstein was an intelligence asset to the apparent entrapment and manipulation and suppression of evidence surrounding J6 to the way the American border crisis is being used to import voters who will pull the lever for social programs offered to them as bribes by Democrats. Nobody believes anything anymore, and it’s happening at a time when AI art and video and deepfakes and voicefakes are all becoming common knowledge.

Our technology is shaping the stories we tell ourselves, and it is shaping our beliefs related to those stories. We trust nothing and no one, and strangely, this makes us susceptible to believing just about anything. We don’t have a reliable standard of evidence for testing claims, and many of us don’t have the instincts or discernment to weed out the obvious disinformation that confirms our priors from the subtle disinformation being used to secretly manipulate us.

This sea change in the way we perceive and understand the world is too chaotic to accurately predict an outcome for. We will come out the other side of this eventually, but what will that look like?

I was struck by a though the other day that dystopian, post-apocalyptic fiction has an opportunity right now, and that opportunity is to offer a vision of hope and sanity. If the house of cards comes crashing down, if the elaborate system of elitist lies finally dissolves the fetters keeping chaos at bay, we will be left with a situation where we are forced to return to something real. In a world where people are forced to band together in real, physical tribes to face external threats, the natural order would organically re-assert itself. Gender roles would return out of necessity. (Sorry Hollywood, but the 98 pound hot chicks will not be defending the compound with their inexplicable martial prowess while the men sit fecklessly by.) Traditional families would become the essential building blocks of revival. Influencers and gender ideology and soccer moms making porn so they can buy Vuitton bags and Range Rovers would pretty much cease to exist. As Jordan Peterson famously said to Joe Rogan a couple years back, “The price of being a prick has fallen to zero [online] but that's not true in real life.” We would be forced to learn that again, and quickly. The people who manage to survive might think, “Well, things are hard now, but they could be worse. We could go back to how it was in 2024.”

But it is borderline insane to think that to return to something like normalcy, we’d need society as we know it to implode.

As this rambling post likely indicates, my thoughts on all this are somewhat inchoate at the moment, but I have a growing sense that this theme — the notion that we’re experiencing something entirely new in human history and that we can’t simply look back to an earlier time for answers — is going to become increasingly apparent to everyone. Many of my peers in the commentariat are still thinking like archeological detectives, laboring under the belief that if we could just stop being part of all the new things, life would get better again.

But in this sense, I think Kale is right. Tech, or at least, the way we use tech, has re-shaped our brains. I mean that in a physical sense, not just a psychological one. We are evolving into a fusion of man and machine, and if we don’t quite see the integration on a transhumanist, cyborg level, it’s only because our integrated tech is not physically inside our bodies. Yet. But pay attention to Noland Arbaugh, the quadriplegic young man who was paralyze in a diving accident who is the first Neuralink implant recipient. This is coming to the masses, and it will happen faster than you think:

A longer video, if you want to understand this more:

Combined with the wave of demographic collapse facing much of the developed world, the diminishing possibilities for globalism as supply chains fail in nations without replacement workers while the Breton Woods era of America defending commerce on the seas comes to an end, our failing social contract and our adoption of radical new technologies will usher in an era of human history we are completely unprepared for.

And yet, I’m feeling weirdly optimistic.

In conclusion, I’m not sure what, exactly, to do with this increasing recognition that we’re in a situation that is fundamentally unique, and if we don’t treat it that way, we’re not going to be able to process the changes we’re witnessing.

I am convinced that the world my young children will inherit a decade or two from now will be almost unrecognizably different than the one we grew up in, and we can’t really predict all the ways that will shake out. We live inside one of, if not the biggest pivot point(s) of history, and only distance will provide perspective.

So I wanted to share it with you, and encourage you to consider and discuss it both here and with your own friends and families.

The preceding was a TSF free post. If you want access to our comment box & community, subscribers-only posts, The Friday Roundup, and the full post archives including this one, you can grab all of that for just $5 a month (or even less on an annual plan) by subscribing right here:

Writing is how I make my living, so if you like what you see here, please support my work by subscribing!

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy me a coffee to help keep me fueled up for writing, you can do that here:

Thanks for reading!

something big is about to happen. When? I'd say within a year. Based on what? Well, I'm 71 almost, and I've never seen things as awful as they are now. Like what? Entrenched Inflation and eye-watering debt levels, men can be women, women sports is not protected (nor women), lawfare (dual "justice" systems--show me the man, I'll show you the crime), rampant crime, open borders where illegals are treated better than citizens, the abandonment of "merit-based" anything, the war on men, the war on babies (up to the moment of birth), rogue Pope--yes, I know there were bad popes before, but this is OUR bad pope, and he is doing massive damage to the RCC. The world leaders in the West seem determined to have WW3. For some reason, the billionaires are buying bunkers. Bezos just bought his third bunker mansion on "Bunker Island". Zuckerberg has a huge bunker in Hawaii. I will not do Twitter and avoid FB--TMI. I don't like Zuckerberg and his 57 genders. And I try to stay out of AI (impossible, I know, but I'm trying my best).

So what to do? Teach your children well, and stay close to God. Prepare for trouble as best you can. Work as if everything depends on you, and pray as if everything depends on God. God is in control, but we are probably in for a rough ride this year and next.