America Needs Religion, Even if You Don't Believe

The following is a paid subscribers-only post with free preview. If you’d like access to all subscribers-only features and posts, you can sign up for just $5/month or $50 per year, right here:

Writing is how I make my living, so if you like what you see here, please support my work by subscribing!

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy me a coffee to help keep me fueled up for writing, you can do that here:

In my last post, I mentioned that the Christian religion, whether you believe in it or not, should be viewed historically as a civilizing force.

The pagan world the Christianity superseded knew how to create order, art, music, philosophy, poetry, and military genius, but was not well-known for its sterling respect for human dignity.

Christianity came on the scene and changed all that. The Western values we know, the jurisprudence we practice, the understanding we have about the value of every human life — these are not things the human race always took for granted. Christendom gave us more than we realize.

But in the West, religion is disappearing. More and more people, myself now included (which always feels strange), are claiming no religious affiliation. Belief is on the decline as many behaviors that were once considered taboo or even uncivilized are on the rise.

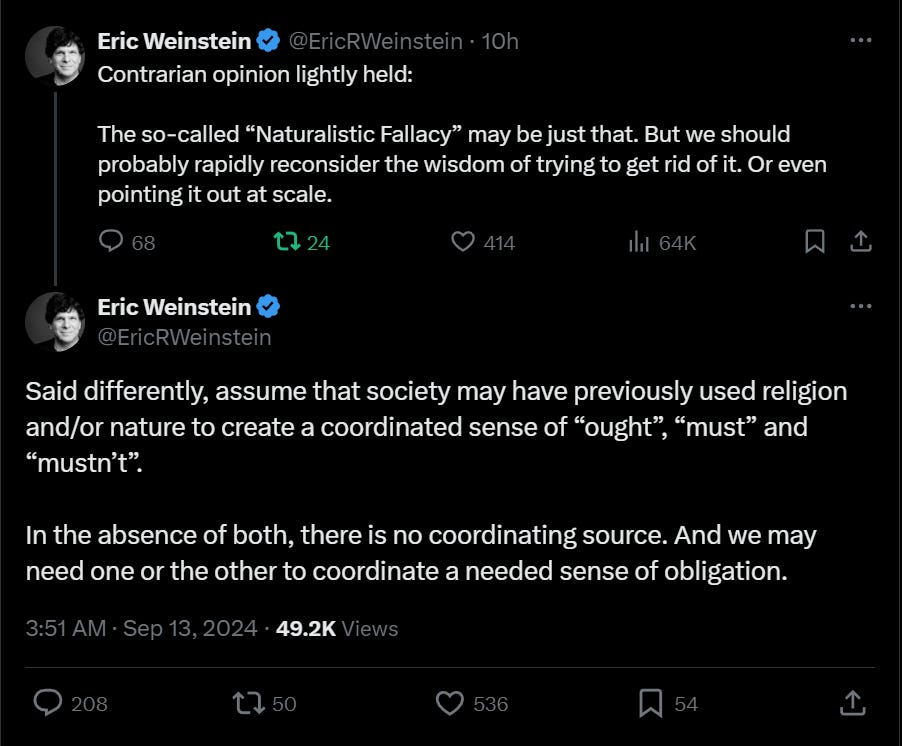

Eric Weinstein, an atheist Jew who carries out aspects of his faith tradition religiously despite unbelief, offered this observation recently, and it resonates:

If you’re not familiar with the naturalistic fallacy, it’s basically the idea that natural things are good because they’re found in nature, and unnatural things are evil because they’re not.

The Christian notion of teleology obviously connects to this. Acts are naturally ordered towards certain ends (ie., sex > procreation) and thus intentional frustrations of those ends are considered, according to this teleological view, to be “disordered” acts. In the language of Catholic theology, disordered acts are evil.

I have come to suspect that the teleological view can be a kind of logical fallacy. For example, perverted faculty arguments around the use of generative organs for non-procreative purposes seem to forget that according to the design of human sexuality, men have involuntary orgasms in their sleep beginning in adolescence, or that most of a married couple’s time together is in fact infertile, also by design. Even in my most fervent time as a Catholic, I couldn’t win nature-based arguments against things like homosexual behavior. I could get close to something compelling, but it was impossible to really close out those arguments. They always seemed to fall short of something persuasive. (The naturalistic fallacy could equally apply to the “but homosexual behavior is found in nature in the animal kingdom” argument, so I don’t just mean to point this criticism at teleology. Some animals also throw poo and eat their own young. But I digress.)

In any case, Weinstein is undeniably correct about the fact that these beliefs about natural law — or religious beliefs that build upon it — create moral codes that can, in theory, be universally agreed upon.

In their absence, all bets are off.

In a way, I feel like I’m having a bit of a debate with myself. I have written before (see below) that I disagree with the Dostoyevskian adage that “if God is not, everything is permissible.” That said, while I think it’s certainly possible not to believe in God but still act morally, in the aggregate, degenerate behavior seems to emerge across populations that are lacking a theistic framework — and yes, the consequent fear of God — that religion (particularly Christian religion) imposes.

I’ve not yet gotten around to reading Tom Holland’s Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. (A gracious reader actually sent me a copy recently that I just haven’t had time for yet.) I expect that when I do, I’ll find little to disagree with in the theme that Christianity took the pagan world from something dark and barbaric and uplifted it to the kind of civilization we take for granted — and are rapidly losing sight of — today. Holland himself was not practicing when he wrote the book, but in writing it, and in the comparisons between the pagan world and the one he grew up in post-Christian Europe, he began to find his way back. As he said: "To live in a western country is to live in a society still utterly saturated by Christian concepts and assumptions."

It would seem that the American founding fathers understood this as well. John Adams famously wrote that

We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge or gallantry would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution is designed only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate for any other.

Alexander Hamilton, who was a non-practicing Christian, supported the idea of a Constitutional ban on non-Christians in public office.

Jefferson was a bit of a weirdo, who thought that eventually, thinking Americans would evolve an enlightenment-friendly religion of some sort; a national creed that all citizens could participate in. In his book, So Help Me God: The Founding Fathers and the First Great Battle Over Church and State, the late author (and Unitarian minister) Forrest Church writes:

The Jeffersonian revival paralleled the explosion of democratic Christianity on the American frontier, known to his tory as the Second Great Awakening. Doctrinally, Jefferson could not have stood further from his most avid religious allies. Believing that a universal, liberal faith would arise from the spread of knowledge, he modeled his approach to religion and politics on Enlightenment doctrine. If Adams was a Puritan skeptic, Jefferson was an Enlightenment priest.

Of the republic’s first president’s views on the civic role of religion, Church writes:

[George] Washington viewed the United States as a religious (not Christian) commonwealth, to be directed by a morally grounded governmental authority. One thing he would not abide was sectarian interference in the affairs of state. More wary of disunion than he was careful of liberty, he slowly gravitated toward order as the nations top priority, with one notable exception: religious freedom. His deep sense of duty to all Americans made him scrupulous to avoid the slightest hint of religious favoritism. Religion was one sturdy pillar of the temple of government he helped design and construct, but Christ, about whom he was deafeningly silent, was absent from the temple's architecture. By the end of his second term, leaders of the established churches had grown openly restive toward Washington’s ambiguous religious posture.

It’s all quite a conundrum. To not believe in it and yet to need it. To understand the power of its moralizing force, but find that in their particulars its morals and teachings are often wanting. To desire deeply to know the truth of it, but know that by design you will never be allowed to fulfill that need.

It’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the human race needs religion, whether or not it’s true.

What does that say about us?

Some might say that it indicates some fundamental truth, written in our hearts. That we are inherently in need of the God of order to order our own lives.

Others might say that we are mere animals who have been uplifted by the evolution of sentience and sapience and that we are in a constant war against our baser nature that is aided by structure and rulemaking and myth.

Whatever the case, it seems undeniable to me that while individual men can flourish and live noble lives absent religious belief, societies tend to fare poorly without it. As someone who remains politically conservative (with libertarian leanings) even after leaving my religion, I cannot dispute that believing Christians are my natural political allies in ways that most non-believers (whether atheist or agnostic) are not.

It’s interesting to see that synergy extend to people of ancient polytheistic religions as well.

During our current election season, Vivek Ramaswamy quickly caught my attention as the most formidable intellectual heavyweight running for the Republican nomination. The way he talks about God in his public appearances is indistinguishable in many respects from the way a Christian running for public office might. But Vivek, though educated at a Catholic school and familiar with the scriptures, is a practicing Hindu. He was asked about this at townhall meeting last year. Specifically, “What do you say to those who say to you that you cannot be our president because your religion is not what our founding fathers based our country on.” This was his response:

Starting by saying he respectfully disagrees Vivek went on to say he is not a ‘fake convert’ and won't lie to ramp up his political career, “I am a Hindu”. Going on to add Vivek asserted that Hinduism and Christianity “share the same value set in common”

“My faith teaches me that God puts each of us here for a purpose, that we have a moral duty to realise that purpose. That God works through us in different ways, but we are still equal because God resides in each of us.”

More than anything, Ramaswamy’s religion may be the thing that keeps him out of high office in a country that is still predominately Christian. But also interesting is the way he’s leaning into his faith to say that we can agree on common values.

Whatever theological quibbles folks might have with that — it’s hard to see an image of Shiva or Kali and not have some questions — it brings us full circle to the idea that human beings seem to flourish when they have something transcendent to believe in, including the consequences for a life lived selfishly.

On a personal level, this is something I really struggle with. I am still sifting the faith I spent so much time learning and sharing and writing about and defending to separate wheat and chaff. I see so much cult-like behavior, counterproductive guilt and fear, superstition and self-contradiction, and I recognize the powerful hold it had over my ability to think and choose freely for the first four decades of my life, and a big part of me simply wants to be free of its authoritarian, minutiae-obsessed, overbearing nature and absurd assertion-making.

But I am not an atheist. I don’t know enough to say what is and isn’t true about the supernatural realm, and the possibility of a god who remains steadfastly hidden from my mind and heart.

Simultaneously, while I am wary of post-hoc ergo propter-hoc arguments, it is difficult not to see that this thing I can no longer make myself believe in has acted as a civilizing force. It has inspired some of the greatest works of human achievement ever seen on this planet. Not just art, architecture, music, writing, but a civilization that is entirely unsurpassed across the span of history.

Now is not the time to shed the values Christianity brought to the West, even though I wince a little bit as I type that. I will remain a critic of many specific things about Christianity, but I will not deny the good it has wrought, and the need we have for something wholesome and decent to counteract the growing darkness in our world.

Less than two months out from an unprecedentedly significant election, I’m forced to take seriously those words written by John Adams, centuries ago:

“Our Constitution is designed only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate for any other.”

Good reflection.

Glad to read that you’re sifting through your prior life. Wheat from chaff, not babies and bathwater.

You're spot on Steve. Who is it that said "If God didn't exist, we would need to invent him."? Two of the young and very smart fellows I follow on YouTube, Joseph Foley and Rudyard Lynch, deal with this matter often. Foley approaches it as an intriguing and haunting question, Lynch as a certainty. I agree with Rudyard Lynch. Although I believe without effort in an ultimate reality that is intelligent and purposeful, "God", I sometimes struggle with believing all the claims the Church makes in his regard. Nonetheless, the conviction that the cosmos, and all of us in it, are in good hands, keeps me sane and helps me to seek virtue in my personal life. History and human experience seem to point to most of us needing some kind of religious outlook. I can't imagine how a democratic republic could function if the majority of its citizens were not actively seeking the good, the true and the beautiful, and were not rooted in some kind of transcendent metaphysical view of life.